Honesti, a rising sixth-grader, edges her hot pink high-top shoes to the edge of a piece of tape stuck to the tiled classroom floor. She concentrates as she prepares to take her shot from the makeshift three-point line. When she sinks the crumbled ball of paper into the garbage can “basket” a few feet away, she cracks a grin, and her teacher, Zach Misak, notes her points on the whiteboard. The competitive game of “trashketball” in this classroom at Conway Middle School in Northampton County looks like a purely recreational activity, but Honesti earned her spot at the three-point line by correctly solving multiplication problems.

The technique is one part of the methodology Misak is learning as part of his training as a corps member at Teach for America of Eastern North Carolina’s residency program. Residencies, which are similar to “medical residencies for aspiring doctors,” are a growing trend in teacher preparation, according to a recent EWA article.

Following an orientation period, Misak and 65 other corps members spend four and a half weeks practicing in classrooms and preparing to guide their own middle and high school classrooms in the fall. The cohort comes from all over the country to eastern North Carolina where they will teach in the fall. Coaches and other staff offer guidance and feedback as the new recruits learn to lead a classroom.

Eastern North Carolina corps members live in apartment-style housing at Chowan University. Living in the region allows corps members to better understand the communities they will serve, says Katy Turnbull, managing director of leadership continuum for Teach for America-Eastern North Carolina.

Instead of focusing on a wide range of topics, the residency program focuses on giving educators a few key items they can implement on day one of teaching, says Michelle Fockler, director of residency for Teach for America of Eastern North Carolina. Corps members practice with each other as students before practicing with actual students, she says.

The class sizes are smaller than those corps members will teach in the fall. Misak’s math class had only three students, a much smaller cohort than he had anticipated. While the class size is smaller, the challenges are large. Students in the residency program are middle school students in Northampton County who are “on the bubble” for passing their grades, Fockler says. The program is not mandatory for the 150 students — almost all of whom are free-or-reduced-lunch eligible— but participation could help a struggling student move to the next grade level. While corps members do not have decision-making authority on promotion, they gather data and make recommendations to principals, Fockler says.

The daily structure differs from earlier versions of Teach for America institutes which often housed corps members in dorms and required structured programming participation after dinner. The function of the residency program is to “mimic as closely as possible what the real teaching year is going to be like,” Fockler says. “You’re going to go home, and you’re going to have to cook dinner for yourself, and you’re doing to have to get all your grading done, and you’re going to have to lesson plan.”

The summer program involves students Monday to Thursday, and each day is divided into three time blocks. In the morning, corps members teach one block in either math, English, social studies, or science. The afternoon time is for corps members to work with each other and with instructional coaches to develop skills. Coaches move throughout the residency program, offering real-time instruction to corps members. Corps members also participate in lunch duty, bus duty, and other tasks around the school.

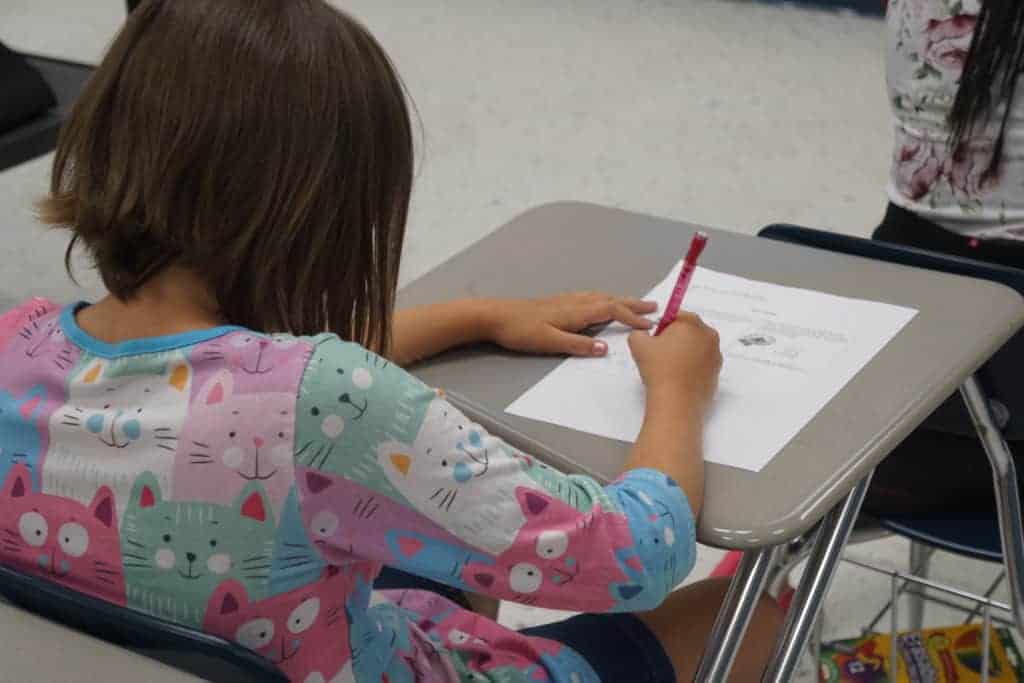

Corps member Kimberly Burton teaches one of the English blocks for rising sixth-graders. Electronic music plays from a laptop as two groups of students worked on exercises about providing supporting evidence in writing. Miss Burton, or Miss B. as the kids call her, encourages students to be proactive in their learning. “If you don’t know something, you ask a question, right?” she says. When one student asks, “What time is it?” another answers without missing a beat: “Time for you to work.”

Mastery of the subject is just one part of the training at Conway. The new teachers also wrestle with classroom management. One math instructor repeatedly instructs students to “work silently” over the chatter of teenage boys. Learning how to address classroom culture is part of the intended curriculum, Fockler says.

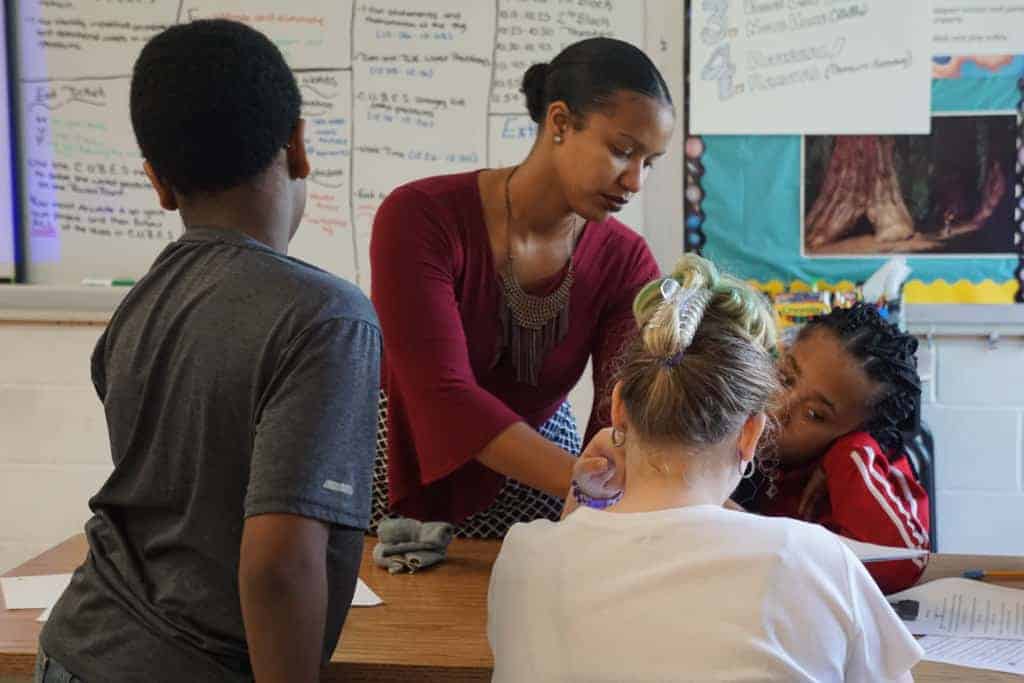

Laura Hebard, a North Carolina State University graduate, teaches rising eighth-graders in their science block in residency. She leads students through a conversation about the way the body uses proteins. As students worked on copying down information for the upcoming lab, a coach huddles with Hebard and offered guidance on the lesson. Hebard nods in agreement and returns to the instruction. The feedback is designed to give corps members an immediate opportunity to make adjustments.

In a break between blocks, Hebard acknowledges the challenge of classroom management. “These students, I am so grateful to them, because they have taught me so much and challenged me in ways, but…we are the notorious class on the hallway for being the rowdy group.”

Hebard says she and her colleagues discuss how working with a small group of challenging students in the summer will hopefully prepare them for teaching a larger group in the fall.

“It has been incredibly difficult and I have by no means have it under control,” she says. “I have a relationship with them now which I’m proud of, but in terms of managing, it is constant.”

Hebard, who will teach ninth grade environmental science at Gaston KIPP school in the fall, looks forward to having a classroom of her own, both in terms of physical space and culture.

In the science class at Conway, she moves the conversation from ways the body used protein to ways the body required oxygen. She asks the students if they are familiar with the recent headlines about the group of Thai boys stuck in a cave and connects the example to a lesson about the need for oxygen.

“What is the problem with being stuck in a cave?” she asks. “You’ve got no oxygen!” a student answers. Hebard segues into a conversation about aerobic and anaerobic respiration. “They found a way to conserve as much oxygen as possible, and that’s what we are going to be doing with our lab,” she says.

The students alternate between disruptive and engaged, but Hebard maintains a positive and energetic tone. She reminds them for the need for raised hands, and she pauses to wait for silence.

“It’s been more challenging in ways that I didn’t imagine, but I have learned more than I ever thought I would,” Hebard says. “And more so coming from just experience more than anything else, I have realized how much the work of a teacher is never done.”