Will North Carolina continue to weight achievement so heavily in calculating school performance grades?

Will it consider new metrics in addition to achievement and growth?

How will it report these grades?

And what data would be most helpful for creating a structured system to re-engage students who fall below benchmarks?

These were some of the questions considered by a state task force on accountability and assessment.

As well as one more question, perhaps the most important of all:

“The challenge is, whose vision?” asked Terry Holland, the director of a consulting group that was retained to facilitate the task force’s work.

“Is it the State Board’s vision through their five goals? Is it a Leandro vision through Leandro? Is it the governor’s vision through economic competitiveness? Is it the General Assembly’s vision through whatever their vision is?”

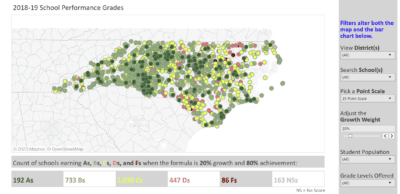

The task force tackling these issues was created in response to Session Law 2019-154, the same law under which the state adopted a permanent 15-point scale for school performance grades. The law asks the State Board of Education to study the weighting of school achievement and school growth scores, currently weighted at 80% and 20%, respectively.

At its November 2019 meeting, the State Board announced the creation of a task force to work with the consulting group, Southern Regional Education Board (SREB). The findings and recommendations from this task force will be presented to the State Board next week, and the State Board will report to the General Assembly by the February 15 deadline set by the law.

On Friday, the task force met for just over four hours, with representatives from SREB breaking the convening into three groups to examine weighting of school performance grades, use of retest data, alignment with the State Board’s strategic plan, and alignment with current findings under the Leandro case.

School performance grades are mandated under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act. That law allows states to use a variety of metrics to determine school performance but mandates that no metric be weighted greater than achievement.

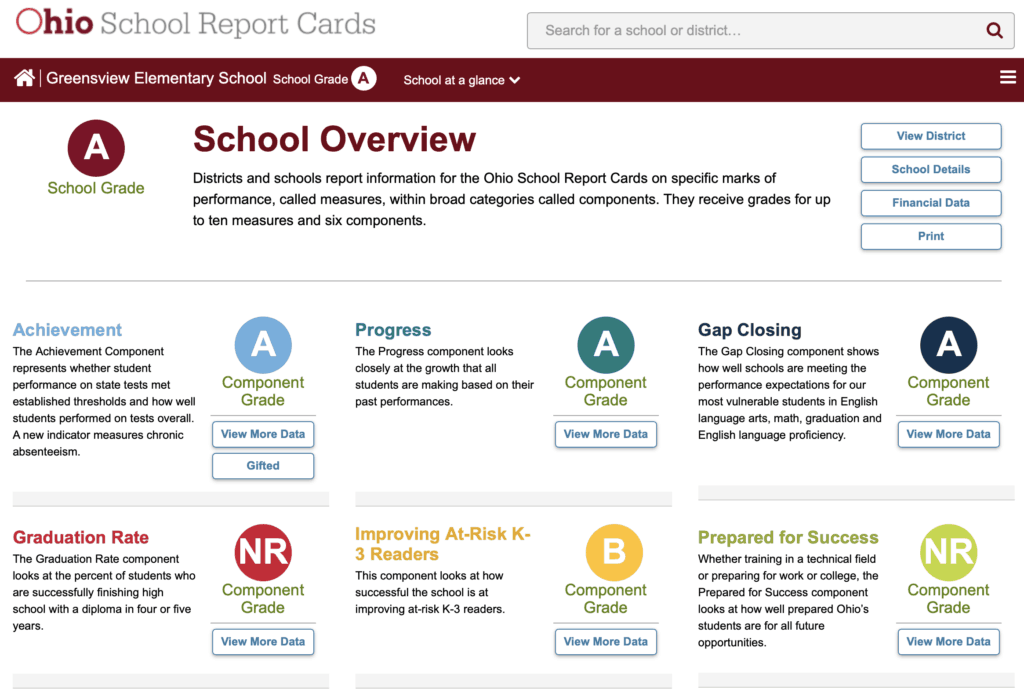

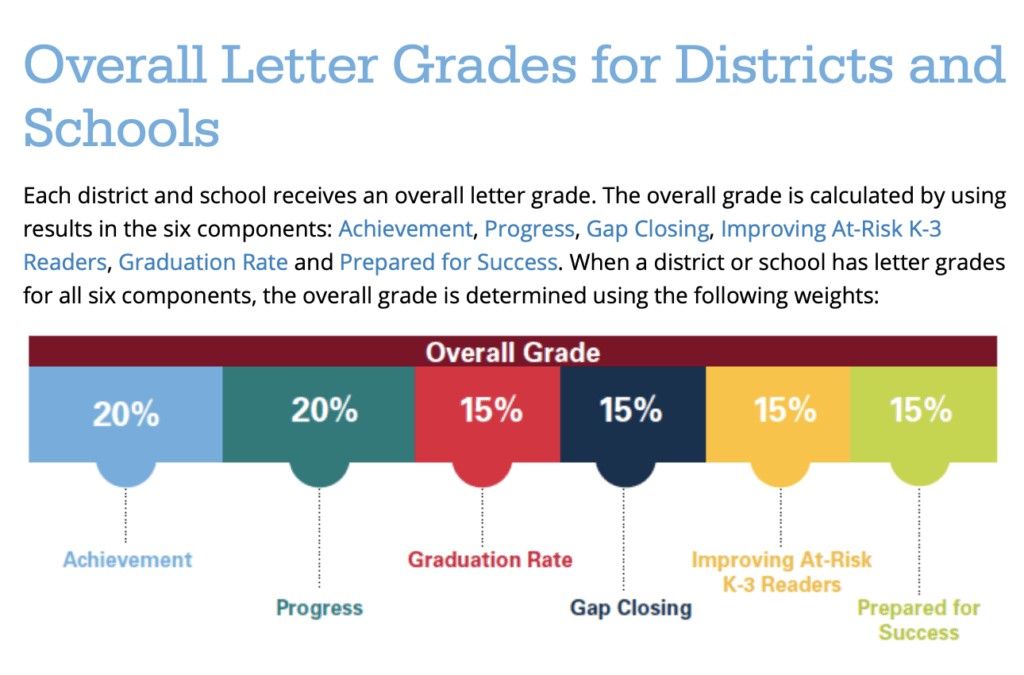

SREB used Ohio as an example, where school performance grades are the product of six measures.

In Ohio, achievement still counts as the greatest metric for determining the school performance grade, but because there are five other metrics, achievement is weighted at only 20%.

While noting that inclusion of both achievement and growth in North Carolina’s measures was a positive, each of the groups reported that they wanted to see other metrics considered. Examples included gap closing and support for innovation. One suggestion was to give schools an open box to freewrite their story, rather than to subject them to assumptions based on numbers alone.

The session law set a “goal of maintaining the current school achievement and school growth measures” but asks the State Board to examine methods of reporting data that will better depict school performance and progress — including:

- Reporting school achievement and school growth separately.

- Reporting by graph, in a manner that depicts the intersection of (i) school achievement and growth scores, (ii) local school administrative unit achievement and growth scores, and (iii) state achievement and growth scores.

- Including the school achievement and school growth scores for the prior two school years in annual graphical reporting in order to provide stakeholders with clear, consistent data on individual school progress.

The task force discussed alternatives to reporting data, such as breaking out achievement and growth by socioeconomic status and also using a scatterplot rather than pie or bar graph. However, more of the discussion involved changing the weighting measures outright.

While SREB will provide its report to the State Board this week and the State Board will present its recommendations to the legislature next week, no substantive change to the current weighting model is likely to happen for at least a year because the state already submitted changes to its ESSA state performance accountability model for this year.

This delay can have a detrimental impact on schools and communities in the meantime, at least one task force member said.

“I work in a school system where I have five to six schools that have ‘A’ for growth but can’t get their heads above a ‘C’ in the school performance grades because our school performance grade model is so dysfunctional,” said Matthew Bristow-Smith, principal at Edgecombe Early College High School and advisor to the State Board.

“And Leandro makes a very clear recommendation … that we need pathways to tease out growth as an indicator and lift that up. If we have to wait two years to make a more holistic, robust school performance accountability model recommendation, then we’ve got two more years in my district where kids think they’re at ‘C’ schools. And that damages our community.”

Holland, whose team has worked with several states on recommendations for accountability model changes, listened to some sharp criticism of North Carolina’s 80/20 model before offering a sobering opinion.

“I hear what you’re saying, but let me give you a reality check: There is no percentage growth and achievement that will make all of your school districts happy,” he said. “Because if you change it, then all of a sudden your high-performing schools will say, ‘We can’t make growth anymore. We’re already at 95%.'”