Mention the acronym STEM, and you might think of electrical engineering, or medicine, or mathematicians, and scientists.

Add “farming” to that list.

Farming isn’t what it used to be. In developed countries, college degrees and GPS-guided tractors are as common in the fields as blue jeans and muddy boots. Soil science and engineered seeds supplement knowledge passed down through generations. In the world’s poorest areas, however, farming is still dominated by less efficient practices. Production is often further hampered by geopolitical, economic, or environmental stressors.

It is here, in these places, that STEM-based farming practices have a huge opportunity to reshape entire regions. For a number of students of the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics (NCSSM), it’s also a chance to stretch their intellectual imaginations while dirtying their hands at the same time, all in an effort to improve food security for millions of people.

Planting a seed

“You don’t think a lot about agriculture being done here,” says NCSSM biology instructor Jon Davis, “but we’re doing it and talking about it.”

And not just with students on NCSSM’s campus. For the last three years, Davis, who teaches a variety of courses in NCSSM’s Distance Education and Extended Programs division, has been encouraging students drawn from the school’s online program, interactive videoconferencing courses, and residential component to consider solutions to global food security and agricultural issues by participating in the World Food Prize North Carolina Youth Institute, a program of the World Food Prize Foundation.

“Thinking about global food security enables students to appreciate what we have here in the U.S. and work hard to enable others to join us in that kind of prosperity,” says Davis. “Of course, those same innovations that have international applications could also be put to use here in rural North Carolina and in Research Triangle Park.”

A new crop of innovators

The World Food Prize focuses on innovations, and the innovators responsible for them, in a wide range of fields directly impacting the sustainability of the global food supply. Through its global and state-level Youth Institutes, it encourages high school students to consider a specific challenge facing food security and present that solution in writing to a panel of experts for review.

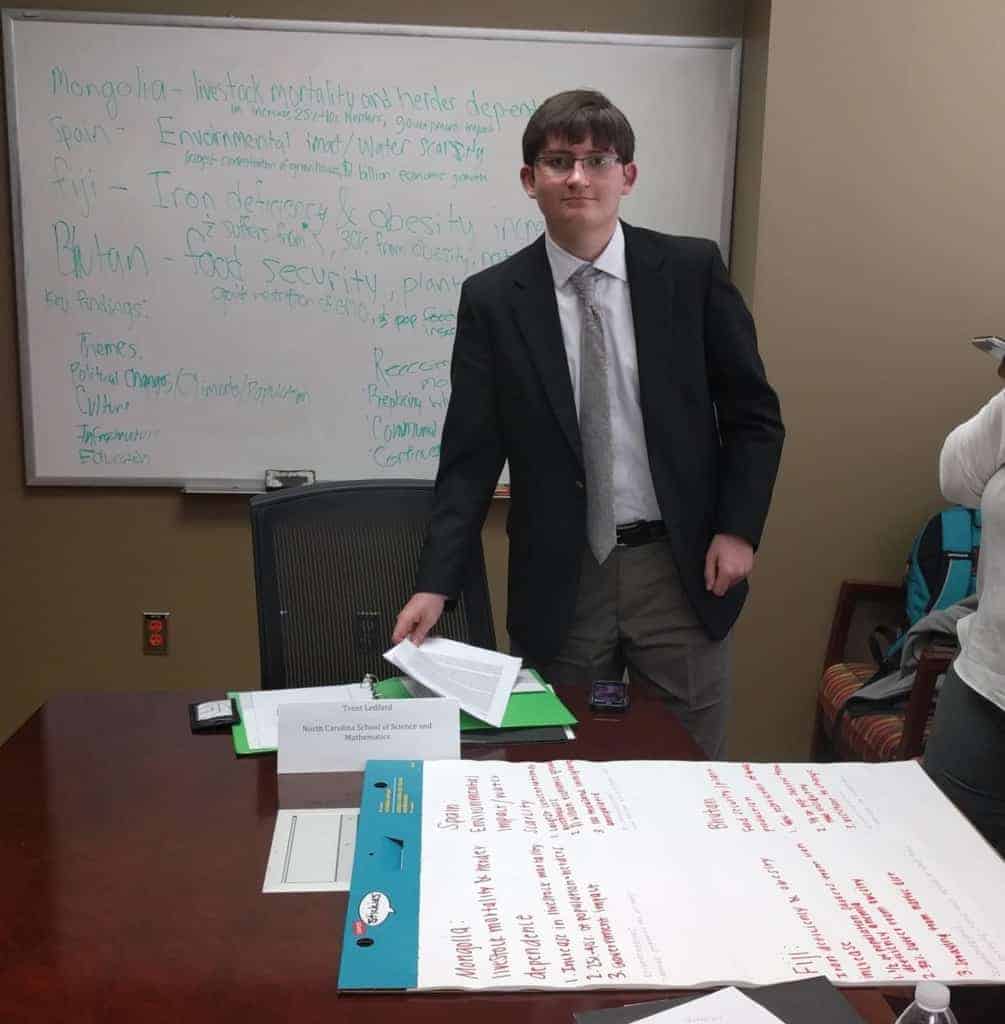

Davis first became involved with the Youth Institutes in 2015. Since then he has mentored 16 students, drawn mostly from his distance-learning classes, in the state youth institute organized by Dr. Lori Snyder, Associate Professor of International Agriculture at North Carolina State University (NCSU). Students heard from guest lecturers with expertise in agricultural sciences, toured the university’s Crop Sciences laboratories, and offered solutions to food production problems in five-minute individual presentations to agricultural science experts from the university. To date, five of those students have been selected by Institute representatives to attend the Global Youth Institute held each fall in Des Moines, Iowa.

“These students are trying to think about how we can apply our understanding of science and engineering and biology to helping the poorest subsistence farmers in the world,” says Davis. “Ending extreme poverty, where people live on less than $1.25 a day, is the number one U.N. Sustainable Development Goal, and helping subsistence farmers boost their yields is a key step.”

An abundance of opportunity

For those students selected to represent North Carolina at the Global Youth Institute, incredible opportunities await. Not only do they get to present their solutions to a distinguished panel of reviewers, they also get to engage with some 400 other student leaders from around the world, interact with global leaders in science, industry, and policy, and meet the World Food Prize Laureates before they receive the “Nobel Prize for Food and Agriculture” for greatly advancing human development by improving the quality, quantity, or availability of food in the world. Participants are also eligible to apply for a prestigious Borlaug-Ruan International Internship which, per the World Food Prize website, provides recipients with an “an all-expenses-paid, eight-week hands-on experience working with world-renowned scientists and policymakers at leading research centers around the globe.”

It’s a tremendous opportunity for high school students, says Davis. “You’ve basically got all these heavy hitters from all over the world coming and participating, and the kids are right in there with them. It’s a great opportunity to make connections for the future.”

Reap what we sow

From megafarmers in Brazil to subsistence farmers in Kenya, one thing is certain: farming is a long game. Patience, planning, immense amounts of hard work, and some measure of luck all play a part in successful harvests.

That’s true, too, in Jon Davis’ classroom. As the world’s farmers continue to cultivate their land, Davis and his students at the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics will be equally hard at work blending farm science with tradition. Who knows what might emerge? A new crop of young people dedicated to global food security, for sure. An exciting breakthrough in food science, hopefully.

And maybe, just maybe, perhaps a future World Food Prize Laureate.

Recommended reading