Libby Belvin graduated from Southern Alamance High School and set out with excitement into her future. She left home for Methodist University to study industrial engineering, chasing a career in high-tech manufacturing.

But after just one semester in college, something wasn’t right.

“I was expecting more hands-on work,” she said. “More actually being able to do things. But it was not like that at all. It was all on the computer and online.”

Belvin was looking at the amount she had to pay in tuition, and she worried she was spending too much on an education that did not fit her goals. She did not feel like she was becoming prepared for the work she wanted to perform.

“It was way too much money,” she said. “And there was no hands-on work. There was no face-to-face with the teachers.”

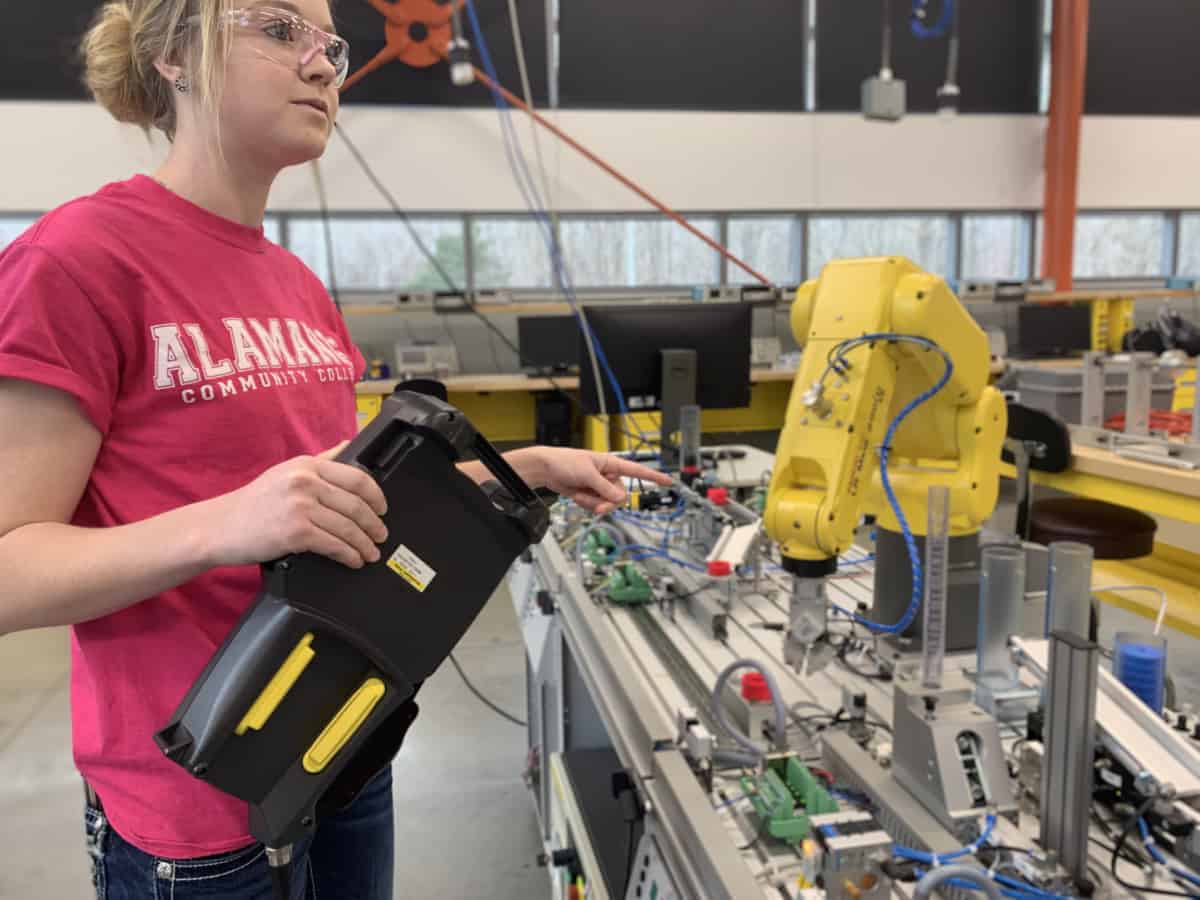

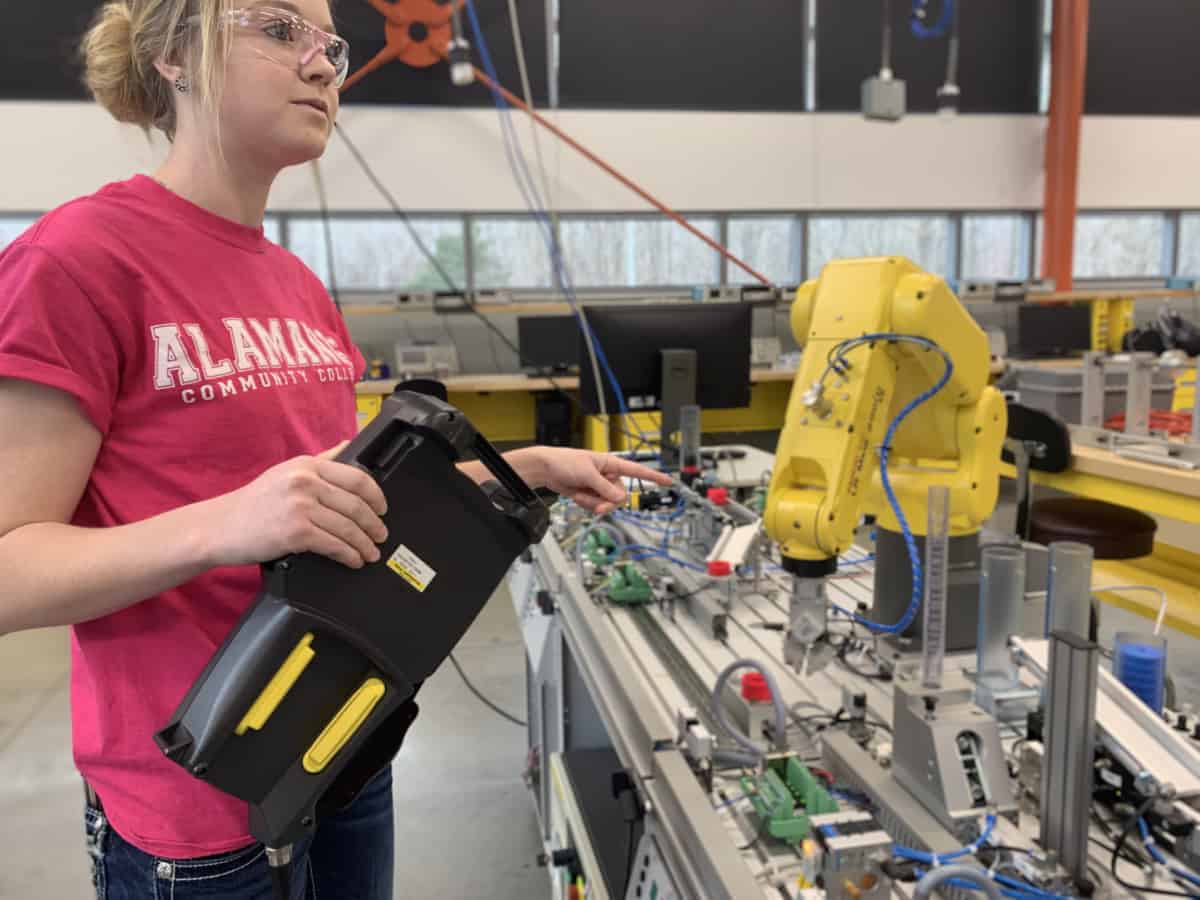

After her freshman year, Belvin left Methodist and enrolled at Alamance Community College (ACC) for a fraction of the cost. She is getting a two-year associate degree in mechatronics and is part of a growing number of students enrolling at ACC for various associate degree programs in hopes of spending less, avoiding debt, and entering the workforce sooner.

“A lot of people have this notion that going to a four-year college is always the best route and that that’s the only way you can really succeed in life,” said Gabriel Redding, who is enrolled in ACC’s Career Accelerator Program (CAP) while getting his associate in mechatronics. “But I think the CAP program and ACC, they’re great examples of why you don’t really need that.”

“Typically, people that come out of college don’t really know where to go to apply for a job,” Redding continued. “And a lot of times, they’ll be out for a year or two before they find anything. And sometimes it’s not even what they went to school for. A two-year degree and experience will take you a lot further than just a four-year degree.”

A walk around the campus at ACC reveals increased efforts around two-year degree programs and preparing students for a seamless transition and success in the high-skilled workforce.

For instance, the mechatronics program is housed in a brand new building with new equipment and a design that simulates a typical workplace.

“We got a beautiful facility, state-of-the-art equipment,” said Justin Snyder, dean of industrial technologies. “We really listened to industry wants and needs as we designed it, and it’s allowing us to really connect with our local industry and business in a way we haven’t been able to before.”

Snyder spoke of an “obvious” skills gap for advanced manufacturing areas in North Carolina. Snyder and ACC invited local businesses onto campus to ask what they needed, what equipment their employees needed better training on, and what skills were essential for new hires. Then they designed a program that would meet those needs.

“We really have designed these programs and this facility based upon those responses,” Snyder said. “Everything in this facility, for the most part, is brand new. We upgraded space and really tried to make it look like a manufacturing facility should look. So it’s not dark and dungy, you know, that you kind of think about from years past.”

The upgrades have been a helpful tool in recruiting. The college noticed an old concept in the minds of parents who were nervous about their kids going into manufacturing. Parents were stuck, Snyder said, in thinking of what older manufacturing jobs looked like. But many of those old jobs have gone overseas. The upgrades and industry-tracking equipment and setting are designed to help visually explain that advanced manufacturing looks very different today.

“It’s hard many times to get parents to understand that this is a career and that there’s great opportunities here,” Snyder said. “So when we bring parents in here and bring students in here, it opens their eyes to the fact that this is high technology. There’s robotics and all these things that they’ve been interested in for years. … The jobs in manufacturing now are very highly skilled. They are very clean, and there’s great potential for our students to come out of here with an associate degree and get a job that will allow them to support themselves and a family for many years to come.”

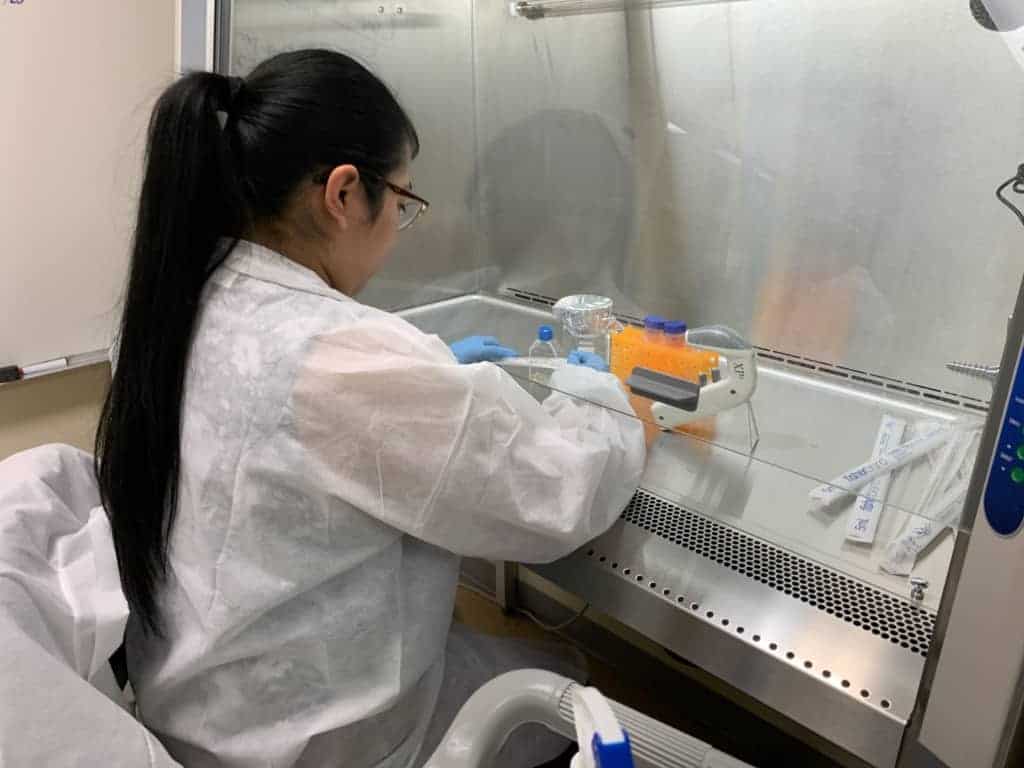

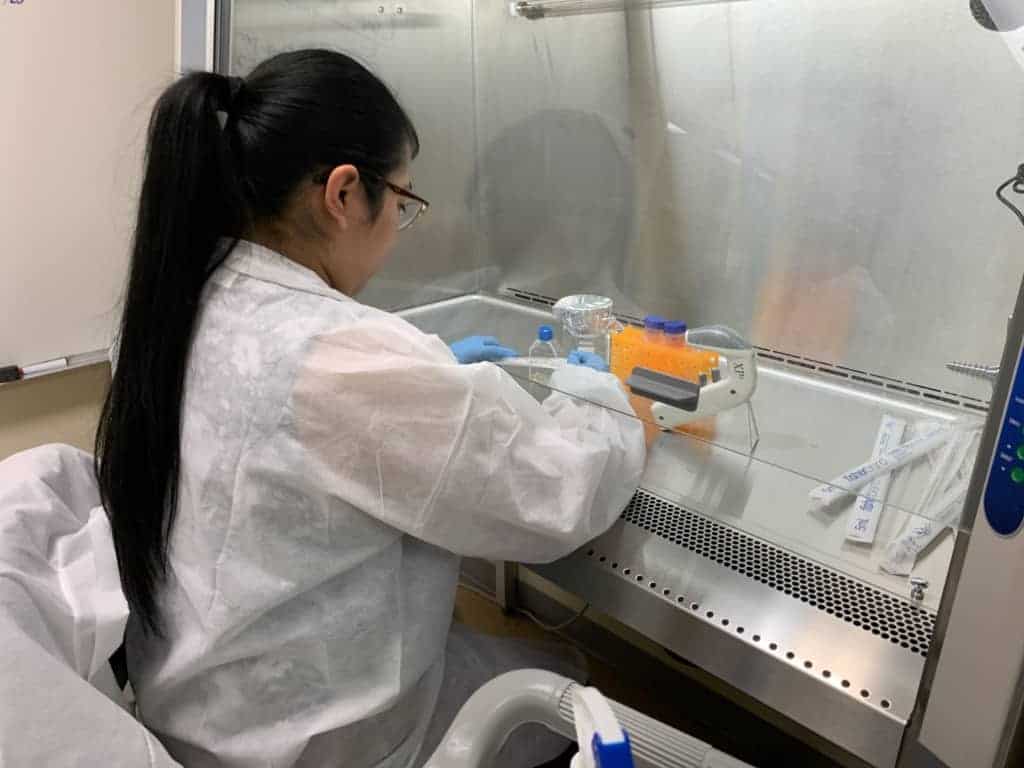

In the biotechnology program, students learn in a lab that looks as if pulled out of an academic center or LabCorp down the road. While some students follow the two-year curriculum and transfer to obtain a four-year degree, that is not the most common track — or the design of the program.

“We are an associate in applied science program and that’s what we’re created for — to produce workforce development graduates,” said Michelle Sabaoun, department head for biotechnology in the Associate for Applied Science department. “We’re not here just to educate for college transfer. We’re here to obtain hard skills and utilize those in the workforce immediately.”

Sabaoun said the school, and her department, have made deep inroads with the local businesses and offer students contacts and networking opportunities as they seek internships, which are required for the associate degree.

It’s that component that drew Adam Hudson to study biology at ACC. Hudson is getting his two-year degree after having already obtained a bachelor’s degree from UNC-Charlotte. He graduated with a degree in biology but was stymied after graduation.

“I had a hard time getting a job in a related field because everyone required either on-the-job experience, which I didn’t have, or a specialized degree, which I also didn’t have,” Hudson said. “So the bachelor’s degree, by itself, that wasn’t really enough, and it was hard to get my foot in the door. The reason I’m in this program is because it does that for me.”

This is a theme across the associate degree programs at ACC – on-the-job training within a classroom setting and contacts for future career. For Tyler Perry, a student in the welding program, that was of utmost importance.

He watched many of his friends go to four-year universities, but he knew he wanted to be a welder. He had been honing his welding skills since childhood, working on his father’s late-model stock cars. In fact, he and his brother now race and work on cars themselves. His focus at ACC is two-fold: Getting more technical skills and making contacts with potential employers.

“It’s not about having a four-year degree, really,” Perry said. “It’s about what you can do and your abilities. If you show somebody that you’re interested in that job, and that it means a lot to you, from your heart, then that’s what makes them interested in hiring you. Because they know that you’re going to be a dedicated person and they know that you’re going to give it your all no matter what. And you’re going to take pride in every single thing that you do, whether it’s sweeping the floors or cleaning the bathrooms.”

Perry has aspirations of owning his own welding company. But he never thought about pursuing a four-year or graduate degree to help him with business. For him, it’s about getting into the workforce fast, gaining experience, and becoming a great welder first. Then, he has other places to go for business advice. For instance, he has an uncle who has run large companies.

“That’s the thing, you know, using your contacts and all this, it saves you a lot of money,” Perry said. “You get the experience that they’ve got over 20, 30 years, and you can’t learn 20 or 30 years’ worth of stuff in four years anyway. There’s no way.”

Todd Spivey would agree. He studied business, among other courses, at UNC-Chapel Hill. He graduated and decided he wanted to work for himself. For years, he traveled the country hunting antiques, loading up a truck every week and bringing his haul back to Mebane, where he and two partners sold them at an auction.

The grind wore on him, though, and foreign imports hurt business. Meanwhile, Spivey would help out a friend who was working a crane to move machines. It sparked a new interest for Spivey in the machines and tools he was seeing. He decided to go back to school for a two-year machining degree rather than graduate school because he didn’t want to take a financial hit.

“I had to fight hard when I got to university to stay out of debt,” he said. “They tried to sign me up for debt, but I said no, I don’t want that. When I got out after the four years, I probably was maybe $3,500 in debt. And I paid that off, you know, 30 bucks a month. But some of my friends weren’t so lucky. They had several thousand in debt.”

Instead, Spivey is learning in the machining program and working for a local business at the same time. Spivey said he had no reservations about using community college and a two-year degree to springboard his new career. At 53, he’s been around a little while and has long since crushed any preconceived notions he had about associate degrees.

But while the students in these programs at ACC speak passionately about it, the administration and faculty speak about prospective students – and breaking down preconceived notions held by them and their parents.

“When I was in high school, our guidance counselors told us if we didn’t go to a four-year school, you were going to end up getting somebody pregnant, you were going to live in a car that didn’t work, your house was going to be up on wheels, and your life was over,” said Mike Holt, department head for the welding technology program.

Even when the message is not so blunt, students sometimes receive the message subtly that a four-year degree is the expected route for postsecondary education.

“You think about our high school students, those teachers that they interact with and those counselors that they interact with on a daily basis, they all have four-year degrees,” Snyder said. “They all went to university, and while that’s a great path, and for a lot of our students that’s the right path for them, what we see is that there’s many students where that’s not what they’re looking for. So we come, we bring them in, we show them what’s here and that we’re very tied with those local businesses and industry. We have to show them what we have here, what it takes to be successful. You don’t have to have that four-year degree.”

Holt recalls a recent conversation he had with a friend of his son’s who got a four-year degree and became a doctor.

“He said, ‘I now owe $600,000,'” Holt recalled. “How long does it take to pay that off? A welder, we’ll spend $5,000 or $6,000 for two-year degree and your first year you might be making $35,000, $36,000. And you leap frog all those pay scales if you want to own your own business; then you’re looking easily at $100,000, $150,000 a year. So let’s just say in six years, you’re even with what that doctor owes.”

Through investments in their two-year degree programs and messaging around strong contact with future employers, ACC officials say they are helping to reshape old ideas around associate degrees. The messaging is helped by attention on growing student debt and the need for advanced skilled labor.

For the students who know they are interested in one of these trade jobs, what better way to get there than affordable training, internships and built-in contacts?

“The ability to come in and learn without the fear of debt is amazing,” Spivey said. “And so for me to just be a part of this, it’s just amazing. I’m like Rip Van Winkle, you know. I feel like I was asleep for 20 years and I come in here and, wow, I get this amazing opportunity.”