Last year, one of my good friends shared a Buzzfeed article with me titled “I Teach For 7 Straight Hours In Stilletos And Never Stop Smiling!” What Stock Photos Tell Us About Teaching. And honestly, I have never felt more understood than I did looking through these hilariously unrealistic stock photos and their captions, each one oozing with sarcasm.

As a first and second year teacher, I had plenty of learning experiences. “Opportunities for growth,” is a phrase I am known for reciting to my fellow teachers and staff. Below are just a couple key lessons I have learned from the myth-busting experience of teaching.

Lesson one: Stick it to SLANT

One of the most important lessons I learned was that there is no right way for a classroom full of engaged learners to look. My students might not all be sitting in SLANT, pencils furiously scribbling every word I speak, and hands shooting up in the air, begging to be chosen to answer a question. This was a tough realization to make, as it is something that many teachers are taught from day one — what an engaged learner looks like.

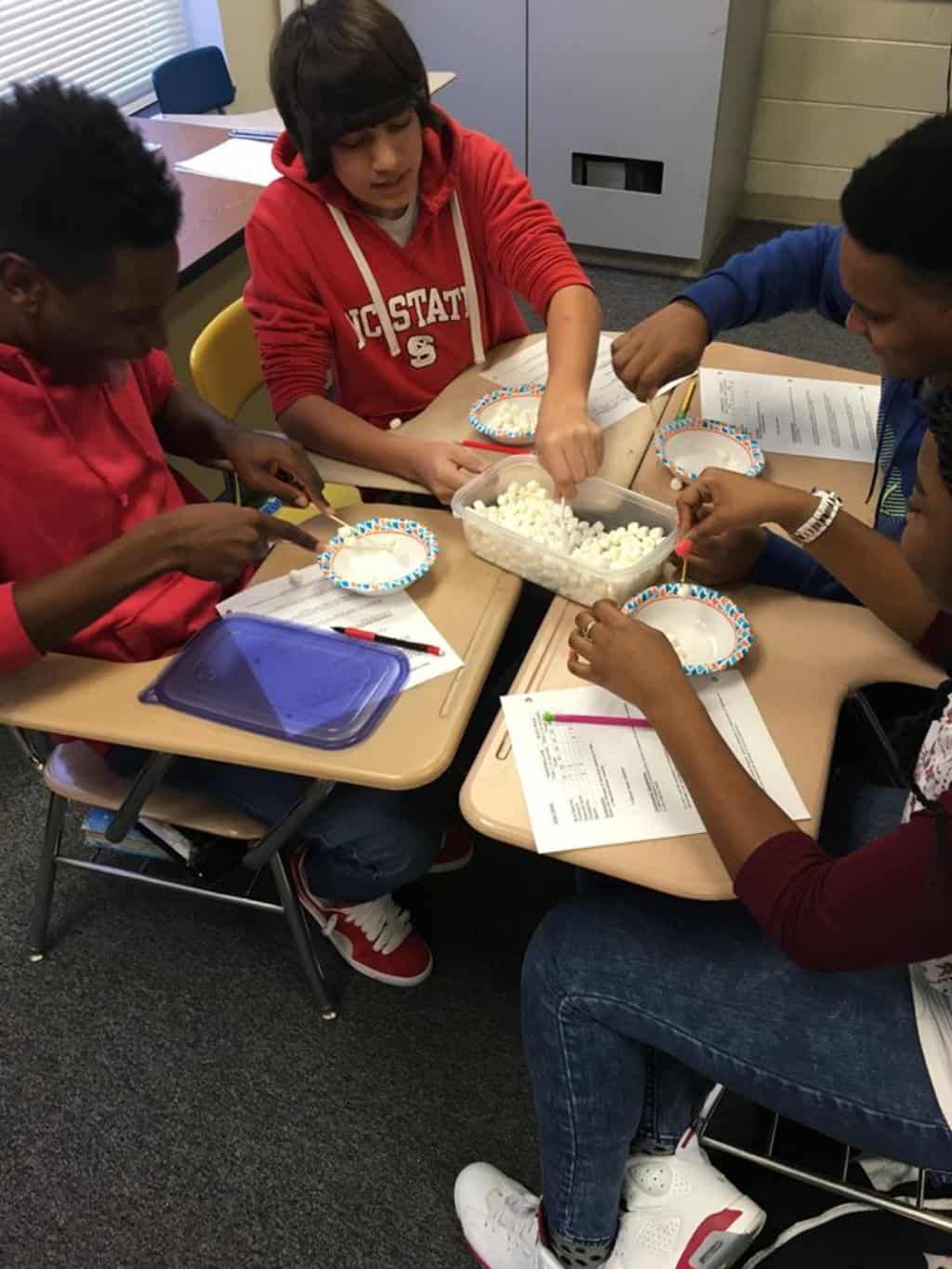

My classroom was known for being a particularly noisy one on the 8th grade hall. On any given day, we would be doing some sort of activity that helped students fully engage with our curriculum and deepened their understanding of a topic. My belief is that if students are able to create something or actively participate in an activity, they are more likely to remember the takeaway objective from that day.

My instructional coach, assistant principal, and principal would often walk in on my classroom full of energy and discussion and (at times) flying objects.

Were they ever concerned that anything besides meaningful instruction was occurring in my classroom? I don’t think so.

Were my students able to communicate key takeaways from lessons where they made their own fossils, mapped out their own geologic time scale showing major events from Earth’s history, or used Twinkies to create models of the sea floor? Absolutely.

Lesson two: Change the mindset from “behavior management” to “responsiveness”

Another opportunity for growth for me was learning that employing a “one size fits all” behavior management style was not going to work for me — or my students. In fact, I cringe at the phrase “behavior management,” a notion that we, as teachers, are responsible for managing students’ behaviors. They are independent, free-thinking individuals: they should be able to manage their own behavior.

Behavior management or classroom management is the notion that teachers are in charge of dealing with disruptive behaviors in a way that allows instruction to run smoothly. Think about it: it’s the preconceived notion that students are going to “act out” and that we, as the classroom manager, need to find ways to react that will remove the disruption and allow other students to learn.

Behavior management is something that is ingrained in all teachers, whether they come from a traditional or alternative education prep program.

But should it be? Shouldn’t we instead be focusing on equipping students with skills needed to healthily cope with stress?

I saw much greater success with my students (personally and academically) when I treated them as individuals with unique needs, rather than participants in my classroom who were expected to adhere to certain behavioral norms.

I saw my students flourish when I adjusted to the role of facilitator rather than manager; when I took time to build a relationship with each student and learn more about where they are coming from and what they are going home to.

Lesson three: Teachers are the first responders in the classroom

I was never explicitly taught about the effect of trauma on a child’s brain until I left the classroom. While teaching, I never knew that the adverse experiences my students carried had influenced their ability to process new information and make “rational” decisions. But I did know that the second I started treating my students as individuals with voices that deserved to be heard, they began to feel safe at school and opened themselves up to learning opportunities.

One of my students from last year, Rayah, always tells me that I would have made a better guidance counselor than a teacher. When I push her on why she believes this, she explains that I took the time out of my day to talk to her about what was going on in her life (which is, in her mind, the role of a guidance counselor). Imagine if every teacher could play that role for every student — how safe they would feel in school, how open their brain would be to new learning experiences, and how much they could succeed with a team of adults behind them.

Rayah was not what most teachers would call an “easy student.” She got angry, and when she did, she made it clear to me and the rest of the class. Instead of issuing warnings and consequences to Rayah, I would pull her aside and ask her what was going on — what happened at home this morning, whether she had spoken with her mom about the argument they had the other day, was she feeling okay? And I responded to her needs.

Trauma Sensitive Schools should be a rule, not an exception

Rayah was not the only student I responded to — this was a model I adapted during my first year of teaching. When a student displayed what would traditionally be seen as “disruptive” behavior, I would pull him/her into the hallway or off to the side and ask them what was going on and how I could help. Because at the end of the day, I was more concerned that my students felt safe and supported than I was about maintaining “control” of my classroom.

I was lucky to teach at a school and in a district that promoted this responsiveness. However, this should not be a novel approach that takes students by surprise. Each and every teacher — whether coming from a teaching training program, a traditional education major, or a lateral entry teacher — should understand the effects of trauma on a child’s brain. And they should be equipped with the tools needed to help their students grow.

The way schools should be, not an exception.