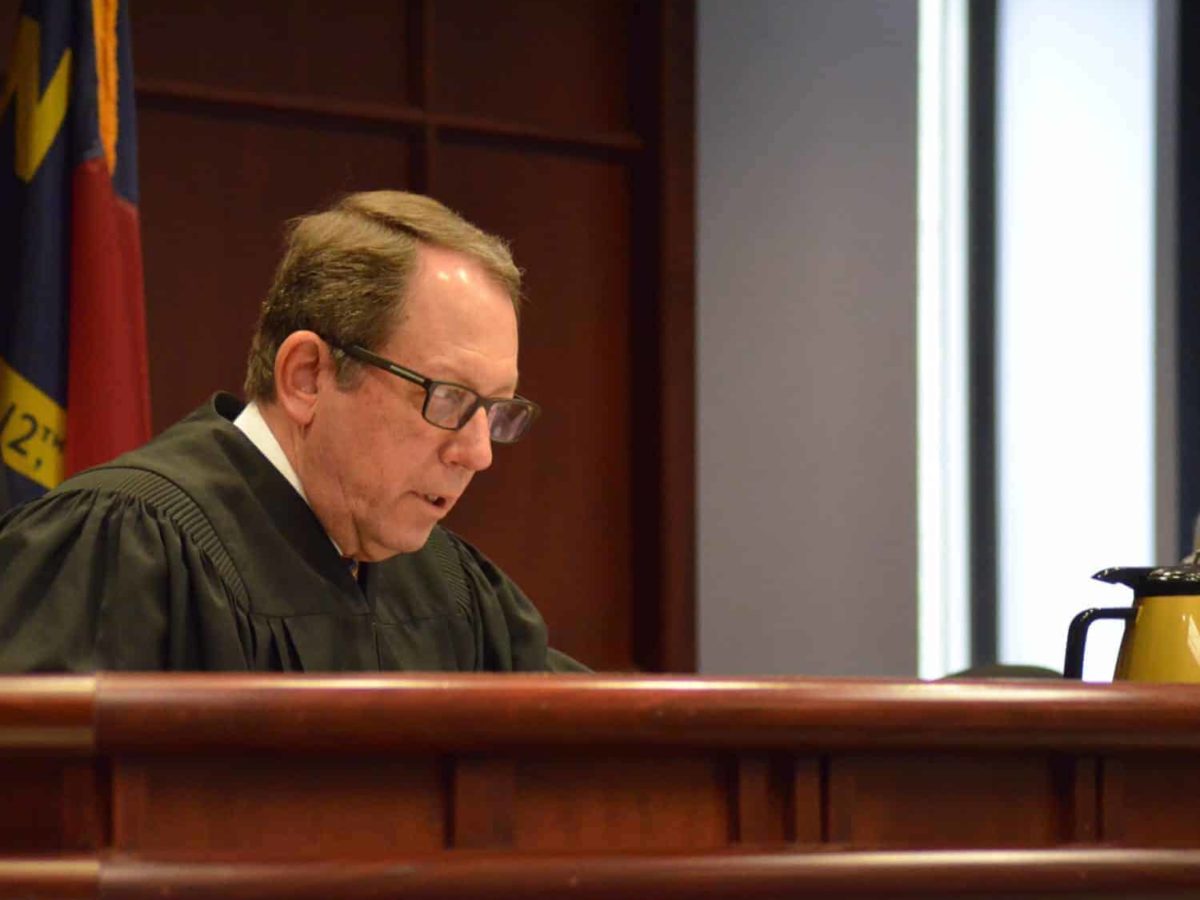

Judge David Lee heard arguments from attorneys for the State Board of Education on why they think they should no longer be defendants in the long-running Leandro education case. Lauren Clemmons, a lawyer with the state Attorney General’s office representing the State Board, argued the state’s education system is far different now and that the State Board has taken steps necessary to ensure that students have the opportunity for a sound basic education.

“The State Board is administering an educational system that has been redone,” she said. “And it’s been redone as a consequence of the State Board’s Race to the Top initiative and legislative statutory changes that have essentially incorporated that initiative into our educational system.”

Melanie Dubis, an attorney with Parker Poe arguing for the plaintiffs — five low-wealth school districts — argued that the State Supreme Court found the State and State Board in constitutional violation of providing a sound basic education for all students in 2004 and that the burden is on the defendants to prove they have rectified the issue. She pointed out that the previous Judge Howard Manning had ordered the State Board to present their plan to remediate their violation to the court in 2015. That hearing never finished.

“He never made that ruling. That was going on when Judge Manning retired and left the bench,” she said. “No court has ever ruled that the defendants have come forward…and met their burden.”

She argued the defendants could not now say they had reformed the educational system without offering proof students have access to a sound basic education, including access to competent teachers and principals, as well as adequate resources. Furthermore, she said that Manning was well aware of some of the changes that had occurred in the state’s educational system and didn’t find them sufficient for the state to say it had met its burden.

“They waited two years. And now they’re coming back before your honor, not Judge Manning, and they’re saying this is all different,” she said.

Clemmons spoke at great length about changes in the educational system, including programs instituted under Race to the Top, a federal education grant program; Read to Achieve; and other state efforts targeted to at-risk students. She also made the argument that there is only so much the State Board can do since it has no money to appropriate funds. That last point was one reason why she said it didn’t make sense for the court to continue to supervise the State Board as part of Leandro.

“The State Board of Education doesn’t fund the school system. It has no power to do that,” she said. “The court should not retain supervisory jurisdiction over a constitutional body that cannot ever fulfill that role. The State Board of Education can never appropriate more funds. It can never raise more tax revenue.”

Clemmons also talked about the enormous amounts of data the state uses to track how students are doing and how effective teachers and principals are. She said those were parts of efforts to ensure the mandates of Leandro were met.

But Lee questioned her as to how she could say that those efforts were working. She pointed out the case of Halifax County Schools, which improved enough to move off the list of low-performing districts in the state.

“Does that mean the constitutional mandates of Leandro have been met?” Lee asked.

Clemmons answered yes and said: “What is the measure if the system is in place and it’s being implemented? There will always be low scores.”

Clemmons also asked rhetorically if the State Board was supposed to act as the guarantor that every classroom had a competent teacher and every school a qualified principal.

Dubis acknowledged the question was rhetorical, but answered it anyway.

“The answer is yes. That is what the state Supreme Court has said the answer is,” she said.

Judge Lee also asked the plaintiffs about efforts to bring an independent consultant onto the case. Back in July, both sides in the Leandro case (Leandro v. State) filed a joint motion that called for an independent consultant to make recommendations on how to ensure quality education for every North Carolina child.

Dubis said an independent consultant had been chosen and that the two sides in the case were almost ready to submit an official order to the court.

Lee said he would probably take between a week and 10 days before returning a decision on the State Board’s motion to withdraw as a defendant from Leandro.

Editor’s Note: EducationNC’s Laura Lee is the daughter of Judge David Lee. Mebane Rash edited this article.

Recommended reading