Kindergarten to Third Grade literacy

The State Board of Education tackled K-3 literacy data during its meeting Thursday. Some students enter school at the appropriate level but then lose reading proficiency during the school year.

Carolyn Guthrie, the Department of Public Instruction’s director of K-3 literacy, said these students are often overlooked by teachers, especially when targeted instruction is needed for struggling students.

“There’s a mindset that when a child comes in at benchmark, that they’re doing okay, and they’re doing fine, and you go about your regular business,” Guthrie said. “But if you’re not checking in to make sure your instruction is working for all those children, you’re going to find that you’re going to lose some of those children.”

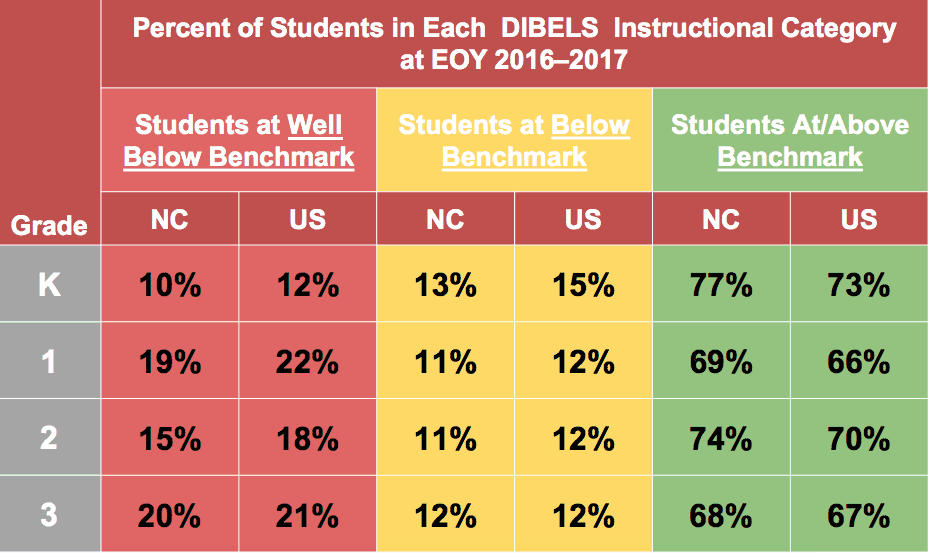

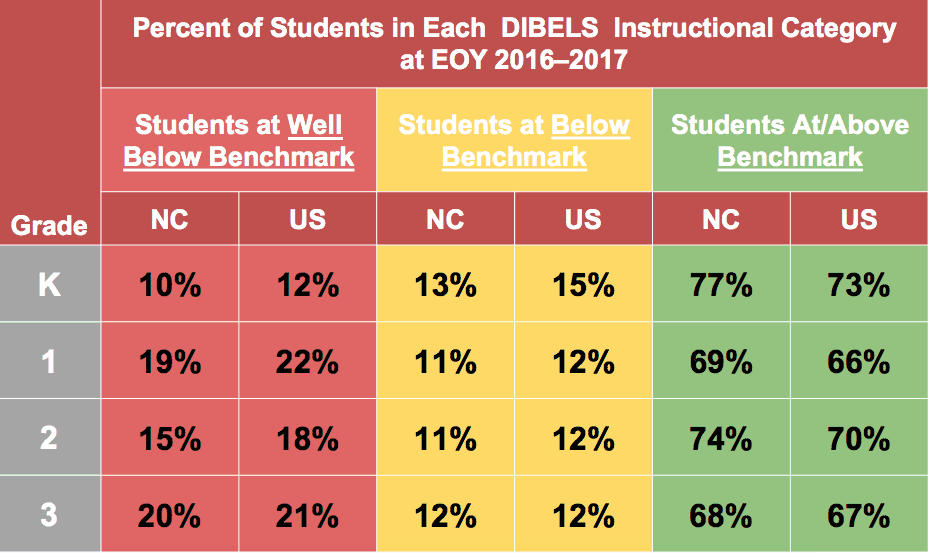

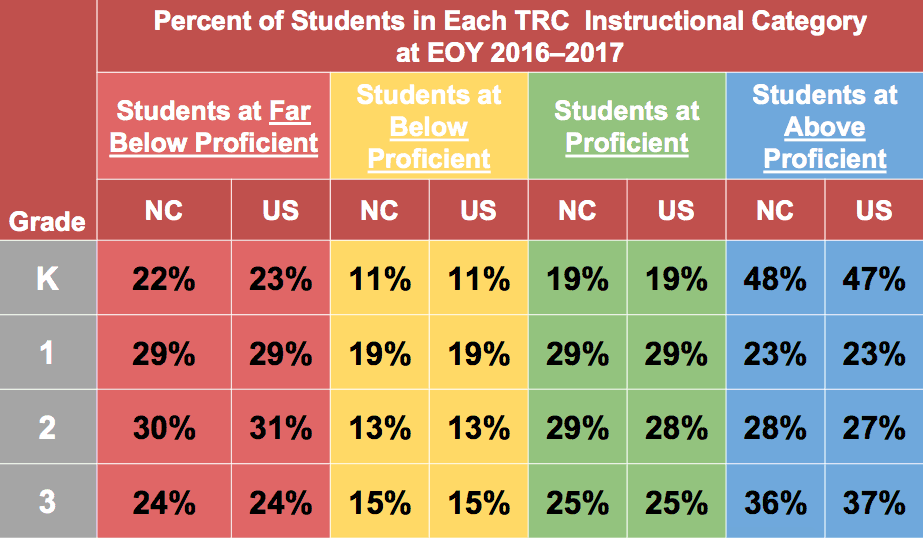

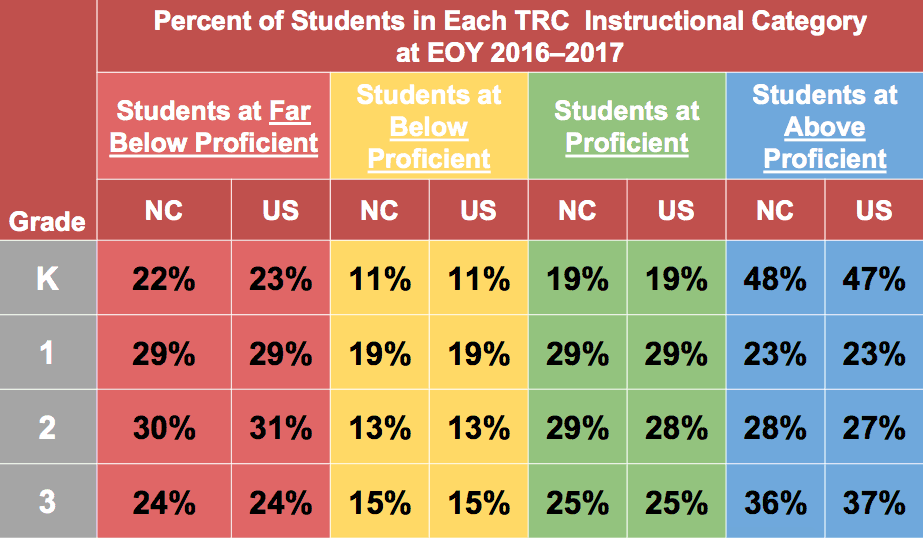

When looking at end-of-year data from two literacy assessments for the 2016-17 school year compared to the national results, North Carolina is about the same and, in some cases, better off than the national average. The DIBELS (dynamic indicators of basic early literacy skills) assessment measures phonemic awareness, alphabetic principle and phonics, accuracy and fluency with connected text, comprehension, and vocabulary and oral language. The TRC (text reading comprehension) assessment, Guthrie said, is more aligned with the state’s standards which guide curriculum.

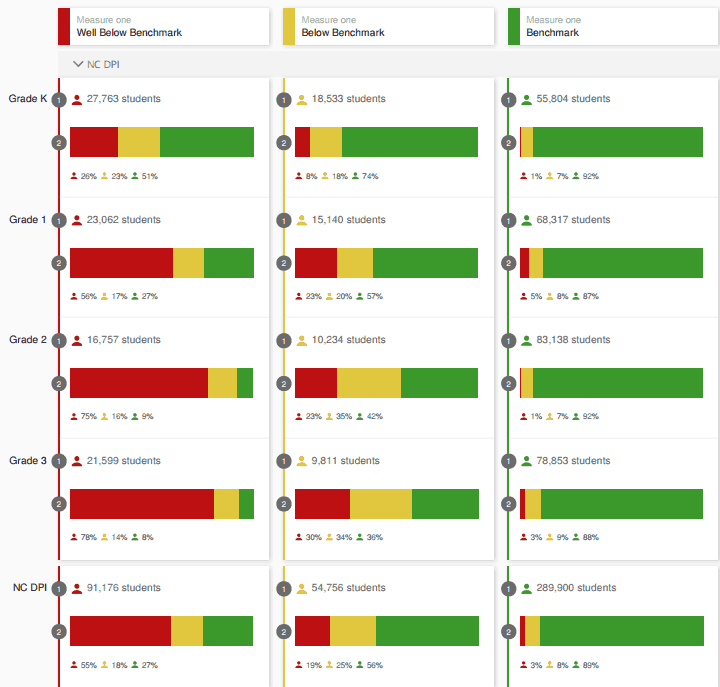

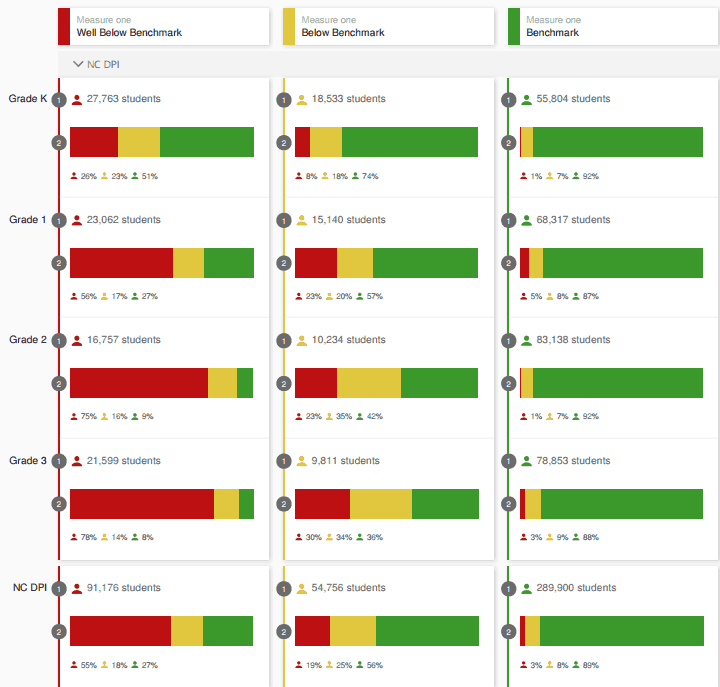

When broken down to see how many students start the year either well below grade level, below grade level, or at grade level, and where they end up at the end of that year, Guthrie says the column that concerns her is the third one.

As the same students move to higher grades, the percentage of students who start the year well below grade level and stay in that category increases.

“As you look down to first, second, and third, you see that a lot of the children that are in the intensive need, are still there at the end of the year as you go on through the grades,” Guthrie said.

Superintendent Mark Johnson emphasized the lack of readiness many students show up with in kindergarten. Teachers, he said, are expected to ensure students are on grade level who are already significantly behind.

“Most of our teachers in North Carolina are doing their job,” Johnson said. “Every year, they have a student in their classroom. They raise that student a year’s worth of growth. One thing we really need to be talking about, for the sake of helping our teachers in that K-5, is when we have students who come in one, two, even three years behind where we expect them to be on the kindergarten level, that is your 720 days. In some cases, in some situations, we are asking teachers to raise those students the reading level from birth all the way to third grade in just that K-3 time frame, on top of all the other challenges that we know these students are facing in those socioeconomic backgrounds.”

Johnson said every parent should be reading to his or her child, starting at birth, at least once a day. He said his NC Reads program hopes to increase family education and engagement.

Guthrie said there are usually around 15,000 to 16,000 students who enter the fourth grade and are not reading at grade level. She said those fourth-graders receive extra support. However, of those students, around 10,000 each year go onto the fifth grade and still are not where they need to be with literacy. At that point, Guthrie said there is no additional support when it comes to literacy, and most middle and high schools do not have professionals trained in literacy on staff.

Vice Chair A.L. “Buddy” Collins said he wanted to keep the focus on those students who are slipping through the cracks of the system. He said teachers should be aware that those students need to make more than one year’s worth of growth.

“We just can not forget these children that we’re systematically leaving behind,” Collins said. “It’s not their fault they come in so far behind, it’s not the fault of the teachers. Teachers are working incredibly hard to get these students to where they are. But what it is a fault of is our system doesn’t recognize the fact that … If it is a condition of poverty, it’s a condition of poverty that stays with them throughout their whole career. Whatever it is that causes them not to be successful is going to be with them throughout their entire career and we have to recognize that in every policy we have, and also in every plan that we have.”

ESSA

The September deadline for the state to submit its Every Student Succeeds Act plan to the U.S. Department of Education is quickly approaching. The ESSA legislation, which replaced No Child Left Behind, leaves much of the specifics of states’ education systems up to the states themselves to decide.

DPI, the State Board, and education stakeholders across the state have been working for months on the plan, and presenting draft versions along the way.

During the long session this summer, however, the General Assembly, in its final budget, laid out those specifics. Starting on page 65, the law provides how schools will be graded, which schools will be identified as low-performing, and which indicators will be used to hold schools accountable.

Several members of the State Board are concerned that stakeholders’ contributions haven’t been taken into consideration. Board member Wayne McDevitt said he has been confused with what’s coming out of all the ideas they’ve been hearing.

“I’m still struggling with the process here a little bit,” McDevitt said. “We’ve been doing this a lot. I’ve even met superintendents monthly and we were meeting with them as a focus group a year ago … A lot of ideas have been on the table and are somewhere on the cutting room floor, and I’m still struggling to figure out what’s on the cutting room floor.”

Johnson assured the Board that they have August to work on the plan and to iron out any differences. He said he sees the plan as a working document.

“This is more of a document that we will be referring to and refreshing often,” he said.

Lou Fabrizio, DPI’s director of data, research, and federal policy, said that although the input will not be included in the plan, the Board and Superintendent have other platforms to express their priorities.

“There’s been a lot of action that’s taken place over the last year and a half, and a lot of ideas that have been expressed unfortunately did not make it into the legislation that tells us exactly what the indicators will be in the ESSA plan,” Fabrizio said. “But there is nothing … that prevents the Board and the State Superintendent from having further discussions on things like chronic absenteeism, on things like physical education, on things like early childhood education.

“All of those conversations, this Board and Superintendent can keep working to come up with things that could be reported on the state school report cards, it could be included in the strategic plan,” Fabrizio said. “I mean there are avenues for the Board to keep making known what the Board and the Superintendent are most interested in.”