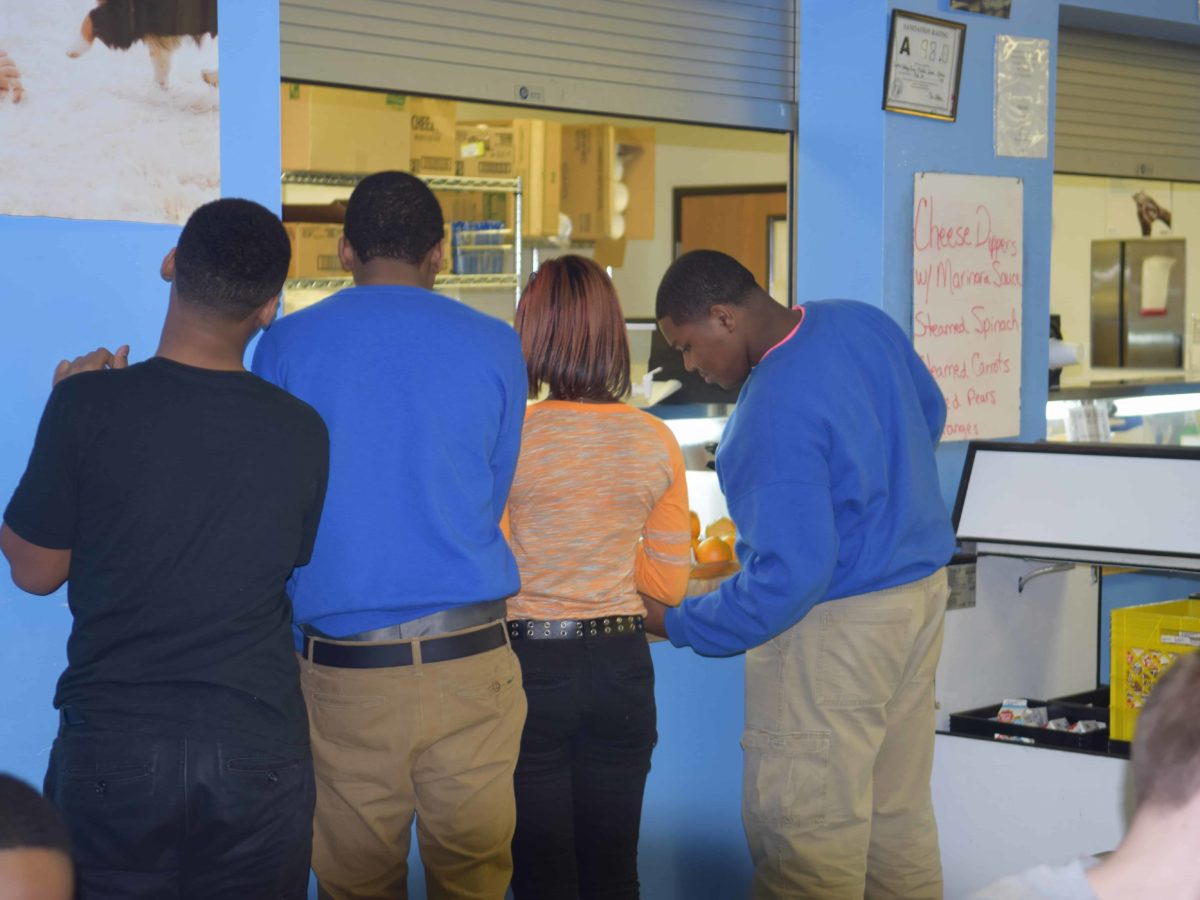

The General Assembly has gone home. And one issue shelved was shifting more public school district funds to charter schools. It was not without some drama, with efforts at the end of the session to push through a bill that did not have consensus among stakeholders. One of the issues that garnered the most attention was shifting funds that would affect student lunches. Charter schools do not have to provide breakfast or lunch to students. Some provide access to a healthy lunch. Many don’t.

House Bill 539, originally a bill on “School Playgrounds Available to the Public,” emerged as a charter school funding bill on September 21. Debate was delayed until Monday, September 28. Debate on the Senate floor focused on the transfer of a portion of “indirect costs” that could include indirect costs related to providing meals for students in the public schools. Senator Jerry Tillman (R-Randolph) argued that if charter schools are to provide lunches, they need the seed money to do so. Senator Josh Stein (D-Wake) countered that the provision gave money to charter schools out of the public school district without any obligation to provide meals. It was “taking public schools lunch money without feeding the kids.” Senator Ralph Hise (R-Mitchell) argued that charter schools need to be able to have innovative approaches in providing lunch and not have to follow restrictive federal requirements. Senator Floyd McKissick (D-Durham) complained that no one could explain the fiscal impact and that “I find it rather disturbing to vote on bill when I don’t understand financial implications.”

While shelved, the issues around student meals has not gone away. Here is some background information:

- Student meals are paid for with federal dollars, not state dollars. North Carolina, while requiring that school districts participate in the federal National Lunch Program, provides the minimum funding required to participate. In 2009-10, the state match was 1.4 percent of total expenditures.1

- North Carolina is in the minority of states in not providing funding for child nutrition programs beyond the minimum. According to the General Assembly’s Program Evaluation Division report, 32 states choose to supplement federal funding.

- School district programs providing meals for children tend to lose money. The reimbursement from the federal government along with receipts from meals paid for by students (full and reduced) do not cover the costs.

- These programs lose money because of a perfect storm: federal nutrition standards have been raised to improve the quality of food and help address critical issues related to overweight and obese children; while well intentioned, the food that meets these standards has less appeal to some students and participation has dropped which affects reimbursement rates; and the costs to provide this food as well as an increase in labor costs makes it more difficult for programs to break even.

- Without any funding from the state, many lunch programs rely on à la carte offerings to boost revenue. These foods do not have to meet federal quality standards and while they may have more appeal to students, the à la carte program then reduces participation in the federal lunch program – and affects the overall nutritional quality of the program.

- The losses are so dire that many school district programs were at the brink of bankruptcy. The General Assembly accepted the recommendation of the Program Evaluation Division that the school districts could not assess indirect costs to the child nutrition program if the program had less than a one-month operating balance.2

- Indirect costs – overhead for functions like finance or personnel – can be assessed by school districts to school-based federal programs. The method is complex.3 The bottom line, however, is the funds received by the federal government for indirect costs are a cost recovery – it is not revenue but a means of reimbursing for expenses.

So what does all of this mean in terms of a requirement, as found in HB 539, to share indirect costs? Philip Price, chief financial officer for the Department of Public Instruction provides this explanation:

Charter schools receive the local fund appropriated to the school district for operations. Therefore, they are getting a part of the funding coming to the LEA for the services the indirect cost is capturing (finance, personnel, etc.). If a charter also receives a share of the indirect cost, they are receiving the funding twice (once with the local share and then for the federal reimbursement for the remaining funds used to cover the costs associated with the indirect cost)… Charter schools also can charge indirect cost on their federal grants. The same rules apply to charter schools.

As we enter the next round of the debate, this raises multiple issues:

If the General Assembly has an interest in making sure that all children have access to a good lunch should the state invest in these programs? This means helping keep the programs in the public schools in our school districts financially afloat. It also may mean finding a way to help charter schools provide a good lunch to their students.

Should refunds of indirect costs or other kinds of reimbursements ever be required to be shared by school districts with charter schools? These funds, after all, are not revenue. They are what they sound like: they simply help school districts recover costs they have incurred in providing education to students in their schools.

If we agree on the importance of children having access to a good meal when they are at a public school – whether a chartered school or in a school district – should the General Assembly consider whether charter schools need to be required to participate in the national lunch program, and if not, the standards to be put in place to ensure a good meal is provided that is affordable or free?

Paying for charter school lunches out of the indirect costs that are recouped by school districts may threaten the public school lunch program. The General Assembly’s Program Evaluation Division report sums up the issue well in this quote of a school district finance officer:

We have been very concerned with the financial stability and sustainability of our Child Nutrition Program for years under the current structure. Increases in food and labor costs over the last several years, along with additional unfunded mandates, have continued to place additional financial burdens on the local school district. The federal subsidy from USDA is not keeping up with cost increases, and with no funding from the state, the self-sustainability of these programs is becoming extremely difficult.4

So let’s start this debate over. Let’s not have it as a part of legislation passed in the last hours of the session. Let’s talk.

Recommended reading