Almost 20 years ago, the North Carolina Supreme Court held in the landmark case of Leandro v. State that every child in our state has a constitutional right to “the opportunity for a sound basic education.” In defining a sound basic education, the Court looked at the educational resources that school districts make available to their students, including access to effective teachers. In the follow-up Leandro II decision, the Court re-emphasized the importance of quality teachers, holding that a sound basic education calls for “every classroom [to] be staffed with a competent, certified, well-trained teacher.”

Student access to certified, well-trained teachers often differs dramatically from school to school however — and far too often depends upon a school’s racial composition. In concluding that racially segregated schools “may fail to provide the full panoply of benefits that K-12 schools can offer,” the U.S. Department of Education’s Guidance on the Voluntary Use of Race to Achieve Diversity and Avoid Racial Isolation in Elementary and Secondary Schools specifically highlighted that segregated schools struggle to attract effective teachers and often have higher teacher turnover rates.

In the Wayne County Public Schools (WCPS) Central (Goldsboro High) Attendance area, the connection between segregation and access to certified, well-trained teachers, is readily apparent. Wayne County serves an overall student population that is 34.9 percent African American. However, African-American students represent between 87.5 percent and 92.6 percent of students in all Goldsboro-area schools. During the 2014-15 school year, teachers with three years or less of experience accounted for 33.3 percent of teachers at Goldsboro High and 42.5 percent of teachers at Dillard Middle, the second- and third-highest percentages of such inexperienced teachers across WCPS. That same year, Central Attendance area schools accounted for three of the four highest teacher turnover rates in the district.

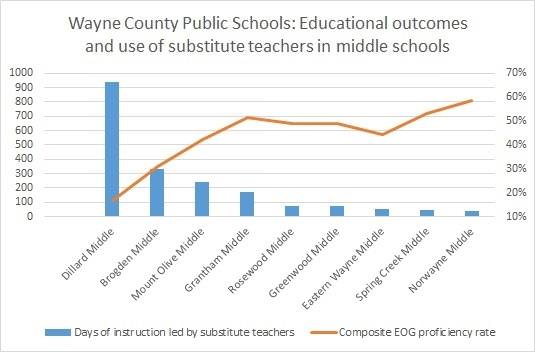

In these same schools, access to certified, well-trained teachers is further undermined by the frequent use of substitute teachers. During 2015-16, substitute teachers led roughly 941 days of instruction at Dillard Middle, the most of any school in the district. By comparison, no other WCPS middle school had more than 331 days of instruction by substitutes. Dillard Middle’s remarkably high use of substitutes was actually a slight improvement, as substitute teachers accounted for more than 1,000 days of instruction in the two preceding school years. Substitute teachers accounted for nearly 458 days of instruction at Goldsboro High in 2015-16. And although Eastern Wayne High has slightly higher use of substitutes, Eastern Wayne is nearly twice the size of Goldsboro High and employs 32 more classroom teachers.

The Leandro cases (like the federal Guidance) recognized the fundamental connection between school “inputs,” like well-trained teachers and principals, and educational “outputs” like graduation rates and test scores. The outputs in the Central Attendance area are no exception. All five Goldsboro-area schools are persistently low-performing; in 2015-16, fewer than 20 percent of students passed all their End-of-Grade or End-of-Course tests at three of the five schools.

Despite the clear rulings in the Leandro cases, many students in Wayne County continue to be denied their constitutional right to the opportunity for a sound basic education. Access to fundamental educational resources depends on where in the county you live. Students assigned to racially isolated schools in the Central Attendance area face one of the foremost barriers to obtaining a sound basic education — lack of access to certified, well-trained teachers. Although the Wayne County Board of Education continues to discuss ways to improve schools in the Goldsboro area, any solution will be incomplete if it fails to address the stark racial segregation and related disparities that exist in WCPS.