“Buenos días!”

“¿Cómo está?”

“Need help?”

“Let’s put on your mask.”

“Let’s put on your backpack.”

It is 7:30 a.m. at Mountain View Elementary in Burke County Public Schools.

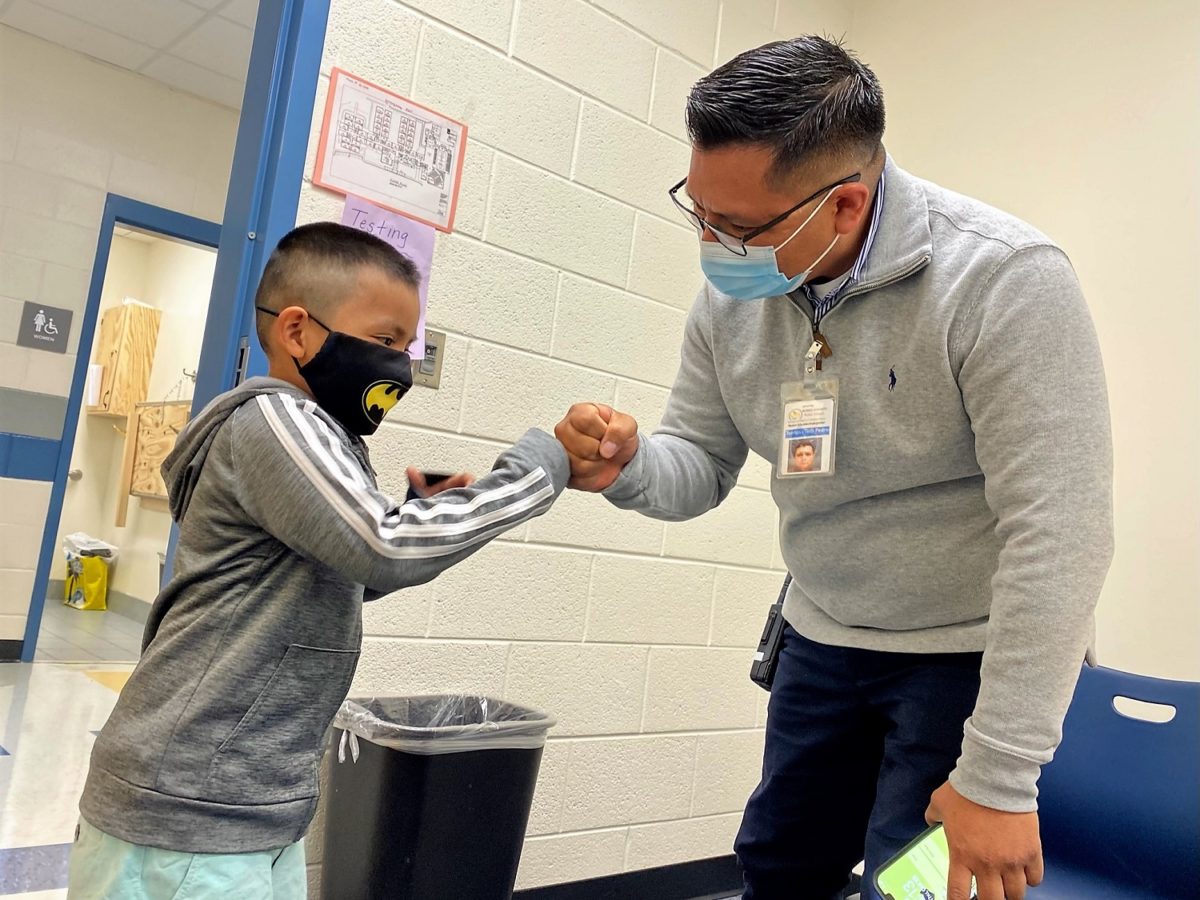

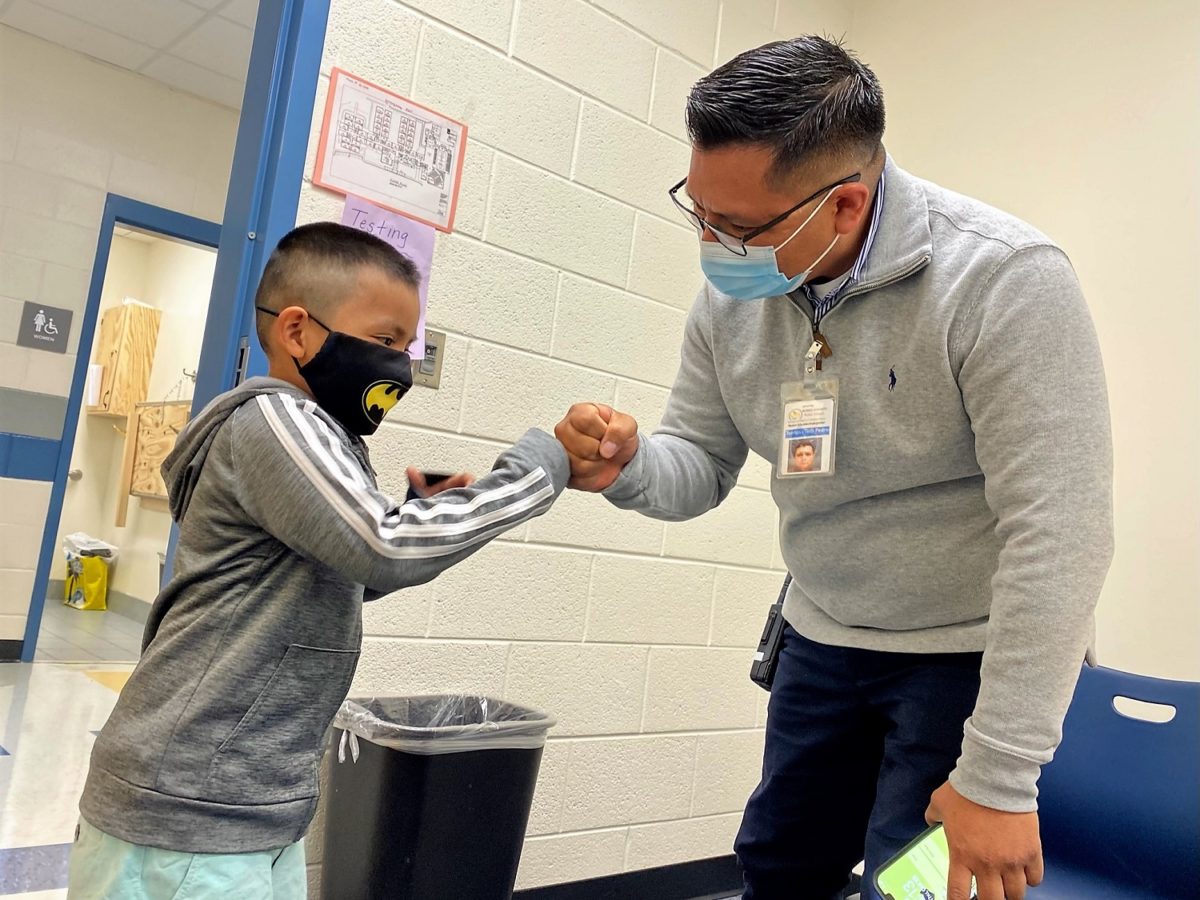

Ted Pedro, the parent educator, is greeting students and families as they arrive to school in carpool. He is here every school day.

He even greets Rosie, a dog in a minivan, who accompanies her family to school. He says she usually barks, but not today.

Mebane Rash/EducationNC

Mebane Rash/EducationNC

Mountain View Elementary is a newer school, about four years old, and Pedro has been here since just months after it opened.

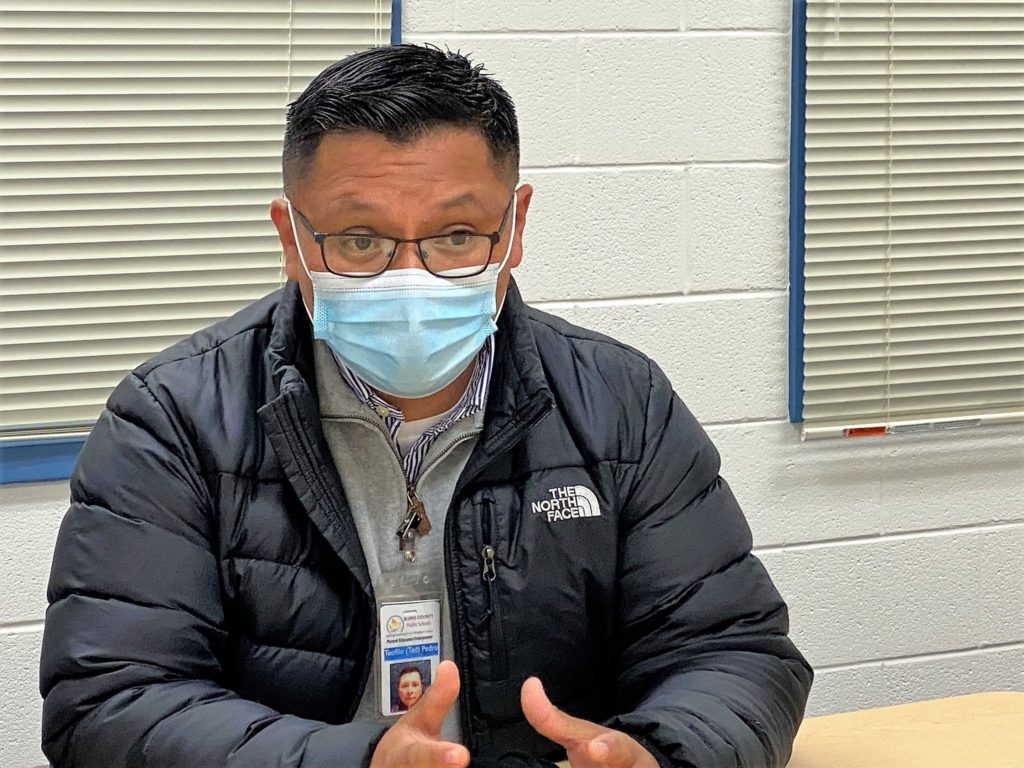

Pedro’s story

About three years after Pedro was born in Guatemala, his parents were persecuted during the country’s civil war and sought asylum in the U.S. He and his brother stayed in Guatemala with his grandma. He says growing up in Guatemala was the happiest time of his childhood. Of those first seven years of his life, he says, “I was a free bird.”

When his mom got sick and almost died, his dad returned to Guatemala to get the boys. They took buses from Guatemala to the U.S.-Mexico border in Tijuana, Mexico.

“Coming here, I remember crossing the border with my dad,” says Pedro. “Going through what we went through. It was like yesterday. They gathered hundreds of people in one place and then from there they just run, and you can see immigration running towards you. As a kid, it feels like it’s an adventure.” He describes border patrol being on horses and four wheelers and also in a helicopter.

He says, “As an adult, you realize you were putting your life at risk.”

“As an immigrant, you will do whatever you need to do to make your life better. It is an American dream if you can reach it. When God blesses you with the opportunity to be in this country, it is beautiful.”

– Ted Pedro

“Especially at the beginning of the year, we had a lot of kids seeking for asylum, moving here to this country, and it was beautiful because I can put myself in their shoes,” says Pedro. “I have been in their shoes.”

Once in the U.S., he grew up in Los Angeles before moving to Morganton in middle school. Pedro graduated from the local high school, aptly named Freedom High School.

A morning with Pedro

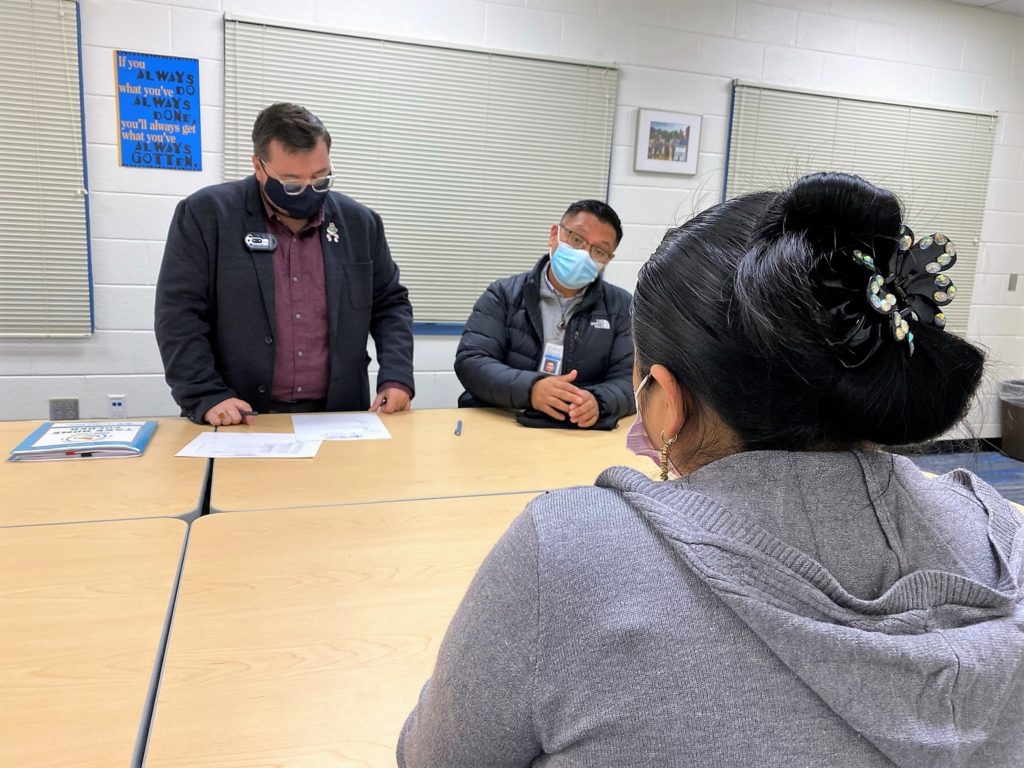

After carpool, Pedro joins a parent conference with a teacher. He is serving as an interpreter. The district has 63 interpreters available to foster communication between educators and parents, including on their website the languages spoken and when the interpreters are available.

Mebane Rash/EducationNC

Mebane Rash/EducationNC

Mebane Rash/EducationNC

But in addition to translating, Pedro is helping this mom understand how things work in the American education system. He is serving as a guide.

Pedro then checks in on three of his students — what he calls “rounds.” He is making sure they are in school and checking in with their teachers to see if they need support. He speaks to the students in a Guatemalan dialect or Spanish, telling them they are going to have a great day. He reminds them to breathe if they get frustrated. This starts the day and the student’s experience of school on a positive note. Pedro says, “It motivates them.”

After rounds, Pedro returns texts and phone calls from parents. The district provides his phone, and he is available to the families he serves 24/7.

The story of one third grader

Pedro introduced me to a third grade student who came to the school two years ago. A “coyote” was paid to transport the student from Honduras to the border. The student was held in a detention center in Texas for 10 months. U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) brought the student from the detention center to Morganton, where the student’s mom lives, dropping the student off on a Monday night.

The student was in school the next day.

“The things that could have happened,” Pedro worries. He struggles to find words to describe the decision of a parent to bring a child to the U.S. knowing all the perils on the journey.

“You gotta do what you gotta do,” he says. “It’s hard.”

Pedro works with the student to unlearn behaviors learned along the way for survival.

The importance of “a good relationship with school”

Speaking in Q’anjob’al, a dialect spoken in Guatemala, Pedro says, “One of my biggest hopes is for each one of these students to grow up and be whatever they want to be.”

“But at the same time,” he says, “I want them to have a good relationship with their parents and especially a good relationship with school just because school will be a very important part of their life for the rest of their life.”

Pedro speaks two dialects from Guatemala in addition to Spanish and English. “That has helped me so much,” he says.

He introduces me to a student he calls by name. His name, he says, is Gaspar, but in dialect it is Kashin. “So I call him Kashin, because that’s his name,” says Pedro.

This story stands in sharp contrast to Pedro’s own story. His name is Teófilo. It means friend of God. Somewhere along the way, a teacher couldn’t pronounce Teófilo, and decided to just call him Ted. It stuck.

There are 610 students at Mountain View Elementary, and 44-48% of them are Hispanic, according to school leaders.

On Pedro and the Quetzal

Pedro has a bulletin board in his office about Guatemala.

The Quetzal is the national bird of Guatemala. It has a green body and red breast with tail feathers more than two feet long. It is described as resplendent, and it is.

One interesting thing about the quetzal is that it does not survive in captivity. The image of the quetzal came into my mind as Pedro was talking about his growing up in Guatemala and feeling like a “free bird.” But once in Los Angeles, not speaking English or Spanish, he describes feeling like he was being “put in a box.” In his own journey and in the journey of his students, Pedro is charting paths to freedom in the day-to-day experience of school and in the longer term experience of what it means to be a migrant in the U.S.

The quetzal is said to be the spiritual protector of the Mayan chiefs. Legend has it that when a Spanish conquistador attacked the Mayans, the quetzal cried out. As the conquistador speared Tecún Umán, the chief, in his chest, the sacred bird fell to the ground coving the chief’s body with its long green plumes. The quetzal then rose from the body with the blood of the fallen chief on its now red breast.

The work of the parent educators in Burke County Public Schools is built around the five protective factors known to be the foundation for strengthening families: parent resilience, social connections, concrete supports in times of need, knowledge of parenting and child development, and social and emotional competence of the children.

With 12 years of data behind it now, the story of the protective quetzal shows up in all of the work of Pedro and the parent educators in Burke County. The return on investment is worth it to the district.

“We know that if the families get these supports, that the likelihood of success is going to be greater.”

Lannie Simpson is the director of English learners in the district. She says, “We are building the future leaders of our community by empowering their parents to allow their children to have the same opportunity as English-only children.”

Parent educators are a best practice for our schools

Many schools in North Carolina need parent educators like Ted Pedro.

According to recent data released by Carolina Demography, “North Carolina’s Hispanic population is now greater than one million people, with 1,118,596 residents according to the 2020 Census. The state’s Hispanic/Latino population grew from just over 75,000 in 1990 to 800,000 in 2010. Between 2010 and 2020, North Carolina’s Hispanic population grew by nearly 320,000 new residents, the largest numeric increase of any racial/ethnic group in the state. Statewide, the Latinx population grew by 40% over the decade, faster than the growth of this population nationwide (23%).”

With the goal of serving these students and families better, on Oct. 28, three parent educators in Burke County — Pedro, Rebecca Wilcox, and Lilliana Zamora — shared their experiences with leaders from the N.C. Department of Public Instruction, including David Stegall, Freebird McKinney, Julie Pittman, and Tabari Wallace; leaders from LatinxEd, including Rep. Ricky Hurtado, D-Alamance; and Dayson Pasión, the director of the governor’s teacher advisory council.

In addition to interpreters and parent educators, across the education continuum, Burke County Public Schools offers support for Hispanic and Latinx students and their families.

The district offers STEPS (Strategically Teaching and Engaging Preschool Students), a part-day preschool program. Pittman says this program plays a key role early on in building trust with the school house.

Mountain View Elementary offers a global immersion academy.

FUTuRES stands for Families United to Resources and Education through the Schools, and it offers family support specialists, parenting programs, and support for grandparents and kinship caregivers.

The parent educators talked with school, district, and state leaders about the importance of families feeling valued. They talked about the importance of communication. They talked about the importance of listening and building relationships. They noted that parent educators serve in a wide variety of roles, including suicide screenings. They noted the need for cultural diversity training for all of our educators. They noted the need to work beyond the walls of the school.

Hurtado says, “For me one of the biggest takeaways is how much leadership matters at the ground level with the parent educators, like Mr. Pedro.”

“We connected,” Hurtado continues, “on so many different elements of our personal lives in the first five minutes, which showed me how he is such an effective parent educator and the bridge he serves between the community and the school.”

Hurtado says while he meets with parent educators and school administrators, he doesn’t often meet with them together. He says in this school system they seem to be on the same page and working together. “You see that in their attitudes and their mindsets and the intentional approaches they are taking,” he says.

The bottom line?

Parent educator Rebecca Wilcox says, “You can’t serve someone in a language they don’t understand.”

Behind the Story

On my next trip, I plan to stop at Little Guatemala, a local coffee shop, where I hear you can often find Rebecca Wilcox, a parent educator, meeting with parents.

My favorite place to eat in Morganton is Asian Fusion.