The Senate’s version of the budget dropped Tuesday night, allocating more than $9 billion for K-12 education over the next two years — more than $600 million more than last year’s budget.

The budget plan went through a series of committee meetings Wednesday and will be be taken up by the full Senate today. Among the biggest education pieces, the plan raises average teacher pay 3.7 percent this year and 9.5 percent over the biennium.

“This is in addition to the substantial teacher pay raises legislators passed in 2014, 2015, and 2016,” Sen. Harry Brown, R-Jones, said to the Senate appropriations committee Wednesday, adding that the budget invests $131 million in raises for 2017-18 alone.

The budget’s salary schedule does not include a raise for beginning teachers or those with 25 or more years of experience. This raised concern from Sen. Angela Bryant, D-Halifax, who questioned why Republican leaders did not choose a schedule similar to Gov. Cooper’s plan which would have raised teacher salaries at all levels.

“On teacher pay, there are still these issues that leave the more experienced teachers holding the bag,” Bryant said. “I continue to be puzzled by that when the governor’s budget could have provided an increase for teachers across the board.”

Gov. Cooper’s teacher pay plan, released in February, aimed to raise teacher pay by an average of five percent over each of the next two years. In March, Cooper emphasized that he wanted to reverse the trend of omitting raises for veteran teachers.

“One thing I know is that there have been some efforts to increase pay of starting teachers over the last few years, but veteran teachers often have been excluded,” Cooper said at the North Carolina Middle School Conference in Greensboro. “And it is important that we value all of our teachers and that we work to attract and retain the best.”

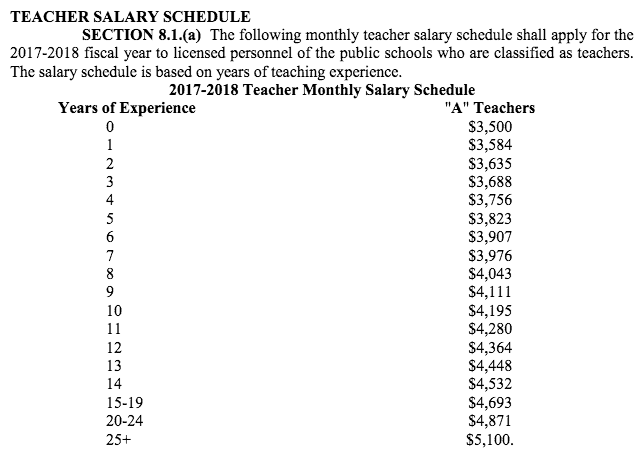

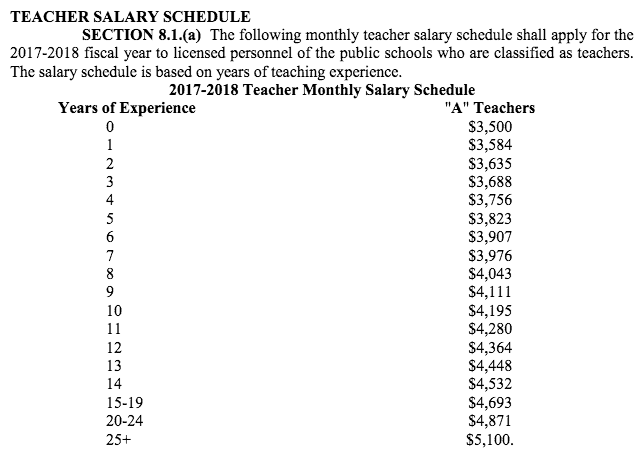

In the Senate’s proposed budget, teachers with nine to 14 years would receive the biggest raises. The following is the Senate’s proposed teacher salary schedule:

“We’re trying to treat [teachers] like professionals,” Brown said. “Because in most professions, it doesn’t take you 30 years to get to the top of your pay scale. And that was the case with teachers before we changed this. So now, this allows a teacher to get there in 15 years and we’re going to try to bonus those teachers for doing good work.”

Brown said the goal of moving teachers to the top of their pay scale sooner is to attract them to go to low-performing schools.

“Those teachers that have the experience and are great teachers, we’d love for them to be willing to go to some of those schools that are low-performing and help correct some of those schools,” Brown said. “That’s the only way we’re going to fix education across this state is to get those individuals to do that.”

The budget gives state employees, including cafeteria workers and bus drivers in schools, a raise of the greater of $750 or 1.5 percent of their salaries.

Senate leaders also included several recruitment tools to attract teachers to the state’s schools. Graduates of an in-state education program who have a GPA of at least 3.75 can start out on the salary scale as if they have one year of experience.

If graduates meet that requirement and choose to teach in a low-performing school, they would start out at the pay of teachers with three years experience and receive that salary for four years. If they choose to teach in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), they would receive the pay of teachers with two years experience for their first three years.

The budget plan also includes the establishment of the North Carolina Teaching Fellows program with $1.45 million in start-up and support funds through the NC Education Endowment Fund. The fellows program would give forgivable loans of up to $8,250 annually for up to four years to education students committed to teaching in STEM subjects or special education at a public school in the state.

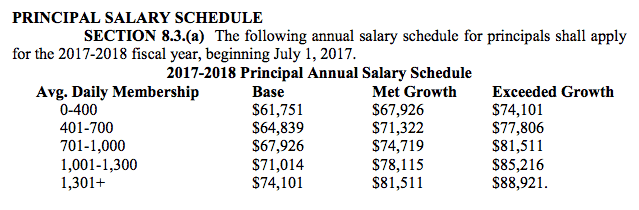

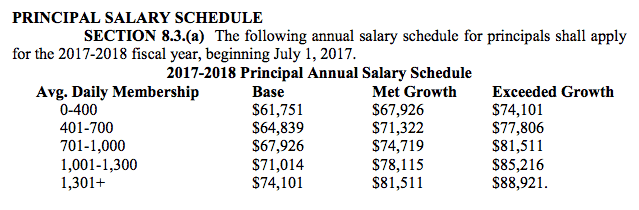

The budget funds more than $28 million of increases in principal and assistant principal salaries. Assistant principals would receive the top teacher salary plus 13 percent. The principal salary schedule is based on average daily membership (ADM) of the school:

“You’re talking about $24 million going to roughly 1,900 principals,” Brown said. “This is a significant investment in principals, and we’re convinced that the right principal in the right school can make a huge difference.”

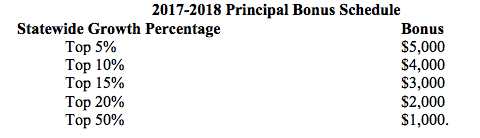

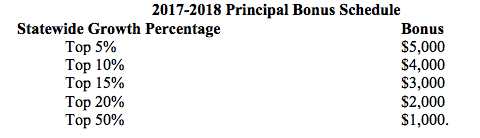

The budget includes bonuses for principals who are in the top 50 percent for school growth in the previous year:

If a principal oversees a school that went from not exceeding expected growth to exceeding expected growth, the Senate’s plan offers a bonus of $5,000 — and an additional $10,000 if that school has a D to F performance grade.

The budget plan cuts the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) operating funds by 25 percent.

The Senate measure would give $432,644 to Superintendent of Public Instruction Mark Johnson to hire five employees in his office. It also allocates $300,000 for Johnson’s office “for legal fees for active lawsuits.” The State Board of Education is currently in a lawsuit with the General Assembly over legislation that would transfer powers from the Board to the Superintendent. Johnson has consistently supported that legislation.

The budget would tighten the rules around how local school districts can use the money allocated to them by the state. Districts, under the Senate’s plan, can not transfer funds from the teacher allotment for grades K-5. The measure follows criticism from Senate leaders on how districts move money around from their intended purpose, namely reducing class sizes. The budget also disallows transferring funds out of allotments for disabled children, academically or intellectually gifted children, English proficiency, textbooks and digital resources.

It does not fund K-5 specialty teachers for subjects like art, music, and physical education, but includes a commitment to create a separate allotment for those teachers in 2018-19 after analyzing data from school districts’ required reports in House Bill 13.

The Senate’s plan gives more than $29.3 million to fund a “business system modernization plan” at DPI to increase transparency and improve the department’s licensure system and overall technological infrastructure.

The budget provides $18.2 million over the biennium to reduce the waitlist by 3,500 students for N.C. Pre-K, the state-funded preschool program for at-risk four-year-olds. The governor’s proposal funded an additional 4,700 slots.

The budget also includes $51.6 million for a driver’s education program that reimburses 15 to 18-year-old students who pass a public or private course and obtain their learner’s permit on the first try. They would receive up to $275.

As the budget document ran through subcommittees and committees throughout Wednesday, debate was limited. In the Senate education appropriations committee Wednesday morning, Sen. Chad Barefoot, R-Franklin, walked through his summary of the education components of the budget, followed by silence from the two members present — Sen. Jerry Tillman, R-Moore, and Sen. Joyce Waddell, D-Mecklenburg.

Later in the day, in the Senate appropriations committee, discussion related to K-12 was mostly limited to teacher compensation. The committee passed an amendment by Barefoot to fund the Governor’s School in 2017-18, which would have been cut by the first version of the budget. In 2018-19, the amendment creates a new school with an attached $600,000 called the Legislative School for Leadership and Public Service which Barefoot says is similar to the current program but does not replace it.

Bryant pointed to non-education budget elements that she said would negatively effect teachers and schools, like limitations on health coverage for retirees.

“[That idea] is not going to make teaching any more attractive,” Bryant said. “At the wages we’re now paying, it lessens the value of that job tremendously. The retirement benefits are one of the reasons people teach.”

Bryant said tax cuts for high-income individuals were prioritized by Senate leaders over education.

“My sense is, when we look at it as a whole, the fact that we start with that billion-dollar tax cut for the wealthy coming out of everything else we spend, then it lessens all the kind of opportunities we have in education, including early childhood — which would probably be the biggest step we could take for the lowest amount of money.”