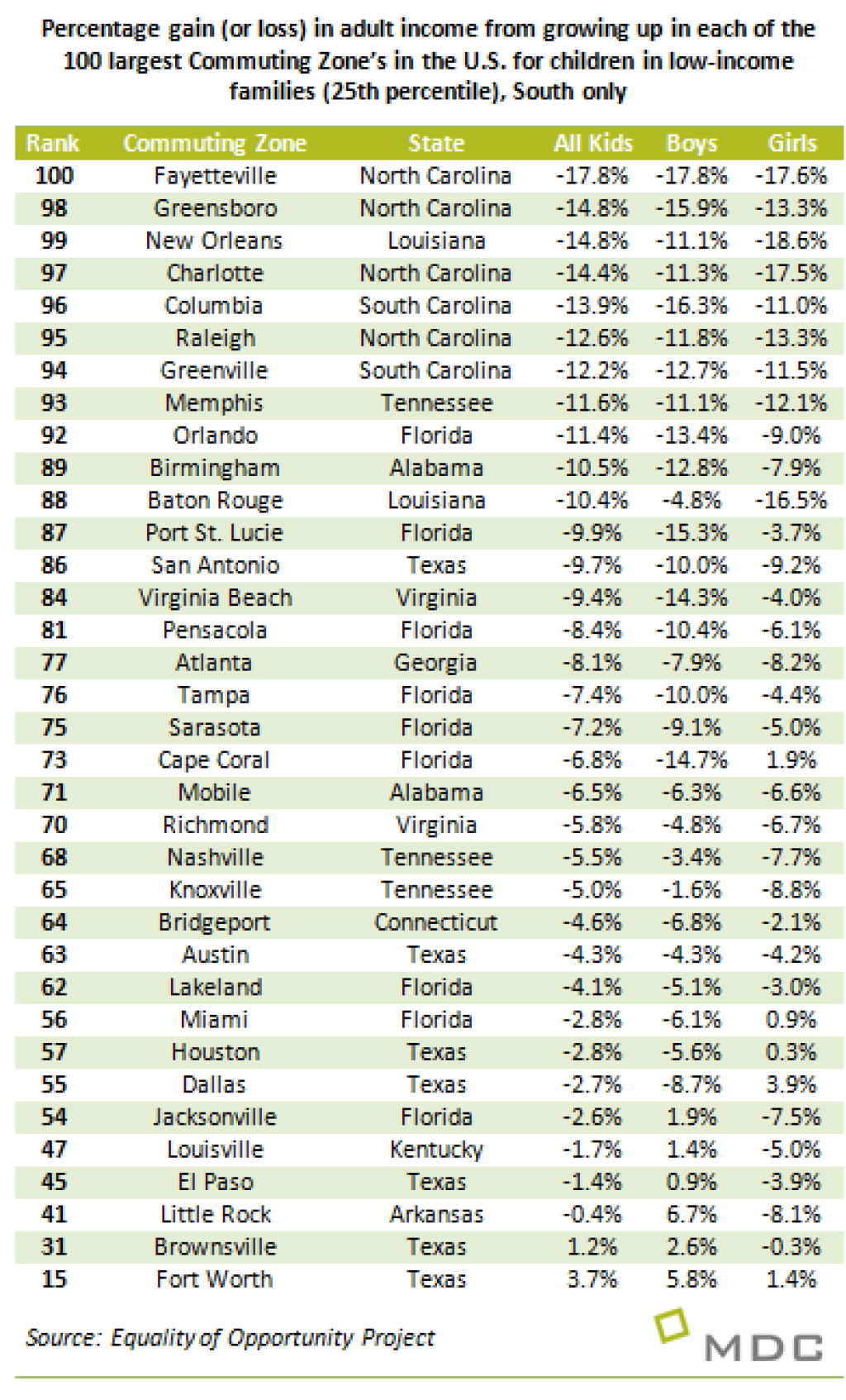

Through much of 2014, I grappled with the stunning research of Raj Chetty and his colleagues at the Equality of Opportunity Project in the course of working with the State of the South team at MDC, the Durham-based nonprofit where I am a senior fellow. What caught our attention at MDC were the findings, depicted starkly in a map, that major high-growth Southern cities, including Raleigh and Charlotte, offered relatively weak prospects for upward mobility to low-income young people.

“Along with their fellow Americans, Southerners have a strong sense that the American Dream has faded in the early years of the 21st Century,” says the State of the South, published a year ago this month.

Subsequently, Chetty and his fellow scholars published additional findings in their exploration of mobility in America. Their 2015 output can be summarized in two words:

Place matters.

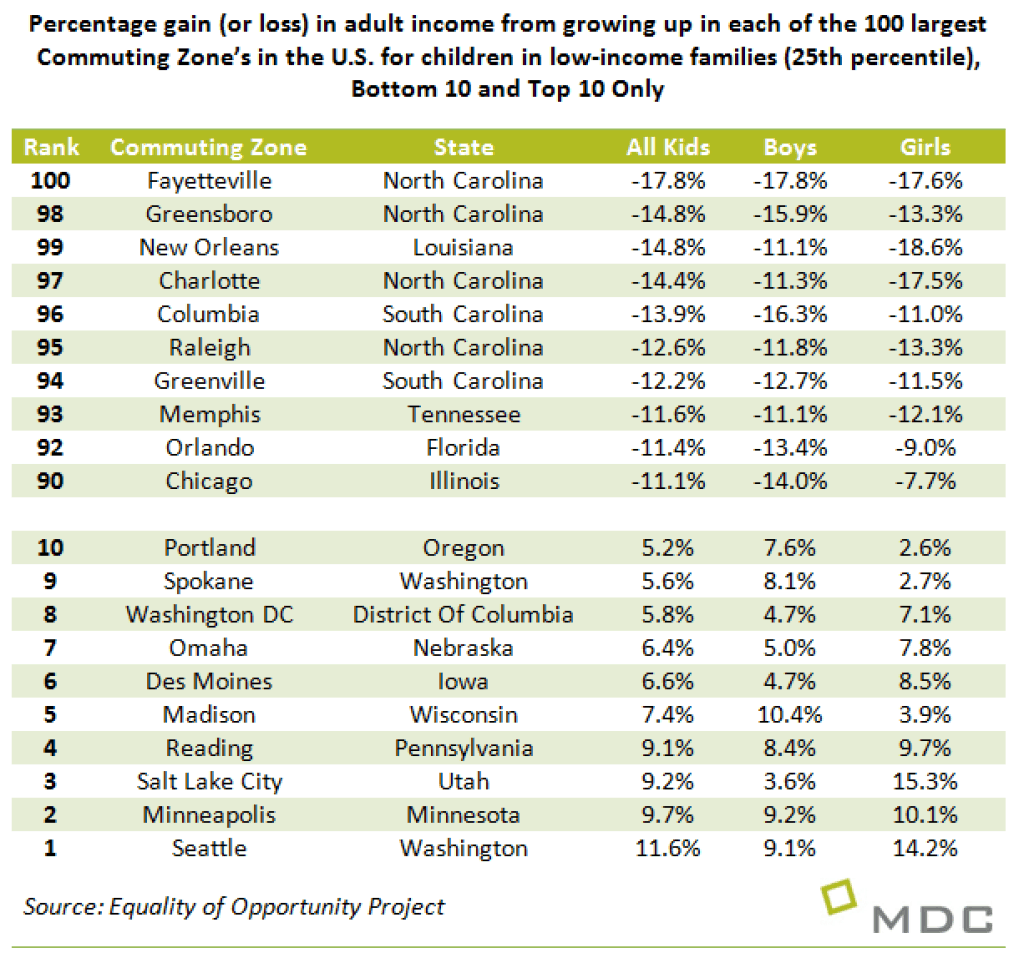

The sheer scope of their study, “The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility,” is impressive. They used tax records to track the changes, up or down, in the economic condition of five million children whose families moved from one county to another in the period from 1996 to 2012. They arrayed data by counties and by “commuting zones,’’ clusters of communities in an economic region.

Their findings are dense, nuanced, and rich in insight. They focus largely on metropolitan areas, and their study is not specifically about education. Still, their work on mobility has important implications for state and local education policy in North Carolina as elsewhere.

The mobility study found that “the neighborhood environment during childhood is a key determinant of a child’s long-range success.” The study contains a chart showing that of the 100 largest U.S. commuting zones, four North Carolina communities rank in the bottom 10 in a calculation of the gain or loss in income of a young adult who grows up in a lower-income household (at the 25th percentile of all households): Raleigh 95th, Charlotte 97th, Greensboro 98th, and Fayetteville 100th. Once again, in-depth research suggests that North Carolina’s metropolitan prosperity does not provide enough mobility lift to many young people in families in or near poverty.

“Within a given commuting zone,’’ say the study authors, “we find that counties that have higher rates of upward mobility tend to have five characteristics: they have less segregation by income and race, lower levels of income inequality, better schools, lower rates of violent crime, and a larger share of two-parent households.”

The study shows that moving from a distressed community to a more robust place can enhance the economic prospects of young people as they enter adulthood. But, of course, everyone can’t move out of every distressed neighborhood – or rural town – so the challenge is to give more people capacity to choose, and to improve their children’s lives, whatever choice they make.

The importance of the neighborhood, say the authors, “suggests that policy makers seeking to improve mobility should focus on improving childhood environments (e.g., by improving local schools) and not just on the strength of the local labor market or availability of jobs.” They stress that “social mobility should be tackled at a local level.’’ And while the study does not identify specific proven policies in neighborhood enrichment, they conclude that “our findings provide support for policies that reduce segregation and concentrated poverty in cities (e.g., affordable housing subsidies and changes in zoning laws) as well as efforts to improve public schools.”

So what’s the message for North Carolina? One is that our state and city governments have a challenge before them to organize an array of initiatives to give more North Carolinians in the coming-of-age generation an opportunity to pursue the American Dream of doing as well or better than their parents. Schools can’t do it all, as the study implies, but schools remain a key component in boosting young people up the social and economic ladder.

Schools are among the factors that determine the quality of a neighborhood, town, or city, and public education is among the levers that state and local leaders can use to enhance the quality of neighborhoods, towns, and cities. Schools are elements in both people-based and place-based strategy.

The Equality of Opportunity Project focuses more on metro areas than on rural places. Still, there is at least an implicit message:

Distressed rural communities need strong schools, even if it means educating young people to leave and thrive somewhere else.

I know this a difficult message for public officials to deliver, because it sounds like abandonment. In fact, strong schools enable people to enhance their lives whether they choose to leave or stay where they grow up. The movement of people from countryside-to-city, from one place to another, is central to the American story.

North Carolina needs educational institutions arrayed to help its citizens pursue the American Dream wherever they seek to chase it.

The Upshot of The New York Times has extensive commentary of the findings of Chetty and his colleagues, including this interactive map showing mobility findings in North Carolina.

Recommended reading