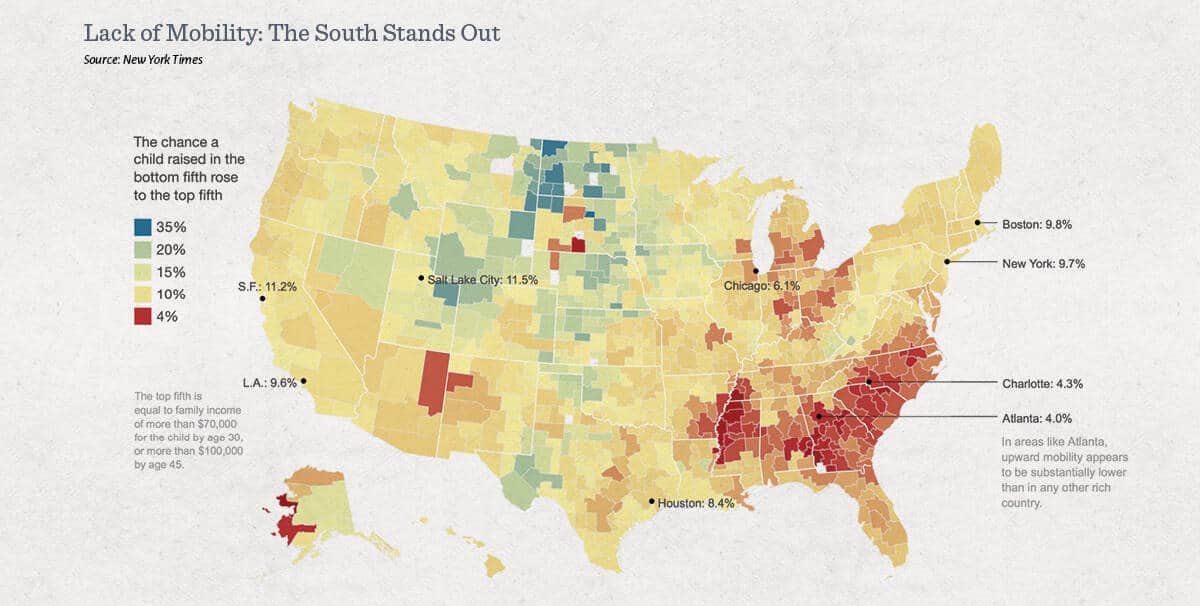

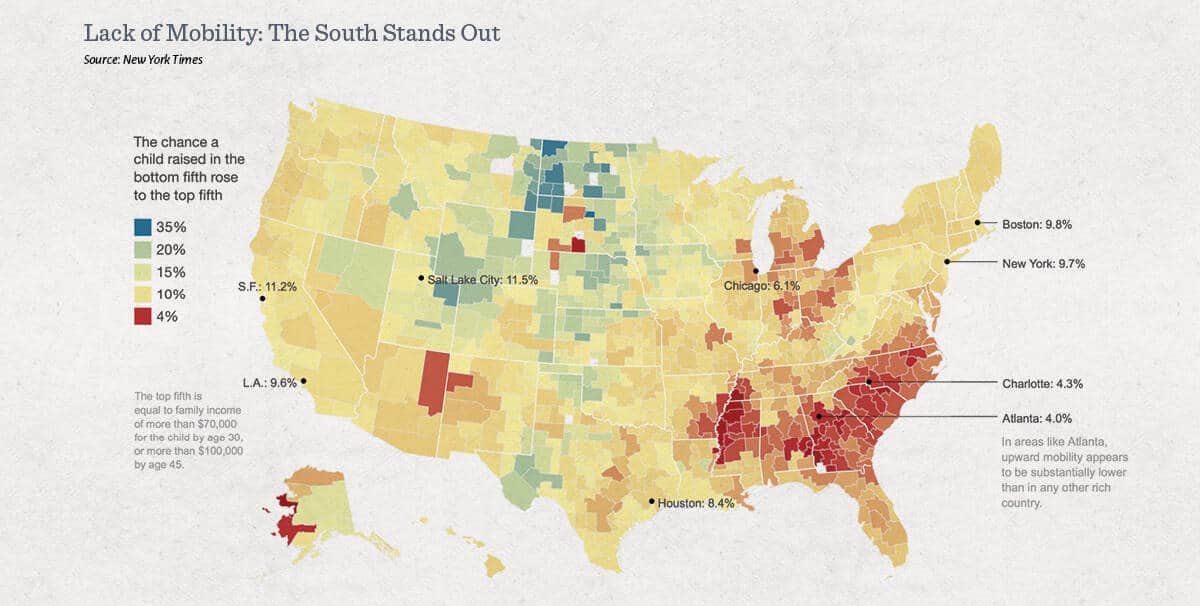

Five years ago, a team of scholars published an illuminating study with an astonishing map that caught the attention of many of us in North Carolina. The map raised an unsettling question: Why does the American Dream appear elusive for so many young North Carolinians?

In its color-coding, the map showed much of North Carolina — and a large swath of the South — in the darkest hue, indicating places of weakest upward mobility. “The fact that children who grow up in low-income families in Atlanta and Raleigh fare poorly is perhaps especially striking because these cities are generally considered to be booming cities in the South with relatively high rates of job growth,” wrote the Harvard-Berkeley scholars led by economist Raj Chetty.

The “Geography of Intergenerational Mobility” report served as a wake-up call especially in Charlotte, which ranked 50th among the top 50 metro areas in economic mobility. A civic Opportunity Task Force was convened, and the Urban Institute at UNC-Charlotte formed a research collaboration with Chetty’s team.

Based at Harvard, Chetty now directs researchers and policy analysts who have continued to produce insightful studies with a mission “to revive the American Dream.” A trove of their mobility research can be found here.

A complementary layer of research, with implications for North Carolina educators and policy makers, arrived this week from the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University. This new report, “Born to Win, Schooled to Lose,’’ does not feature a striking map, but it opens with a blunt message: “The American Dream promises that individual talent will be rewarded, regardless of where one comes from or who one’s parents are. But, the reality of what transpires along America’s K-12-to-career pipeline reveals a sorting of America’s most talented youth by affluence — not merit.”

Led by Anthony P. Carnevale, the Georgetown center contrasts the prospects of children from poor and affluent families. A poor child with high test scores in kindergarten has a three in 10 chance of getting a college education and a good first job. An affluent child with low scores in kindergarten has a seven in 10 chance of such achievements. Affluent families provide their children with stronger uplift when they stumble in the K-12 system.

The center’s report offers a glimmer of hope. High school students from poor circumstances — including black and Latino teenagers — have an increased chance of academic and economic success if they keep their math scores in the top half.

And yet, says the report, “the likelihood of success is too often determined not by a child’s innate talent, but by his or her life circumstances — including factors that determine access to opportunity based on class, race, and ethnicity. In short, the system conspires against young people from poor families, especially those who are Black or Latino.”

The Georgetown center calls for wider access to pre-K. The center also recommends an expansion of high school counseling to give students more information and social supports to facilitate their transition to post-secondary education.

“We need to use education to clear the pathway to opportunity for all, regardless of background,” says the Georgetown report. “With adequate resources, schools can influence students’ development of skills and abilities and, ultimately, their socioeconomic mobility.”

Of course, whether North Carolina devotes “adequate resources’’ to its schools stands at the center of the state’s great debate. So much of political and legislative debate seems narrow-gauge, focusing on percentage points and incremental rankings. A wider scope would ask how can North Carolina — even its robust cities — put more of its young people on a trajectory to achieve the American Dream.