Share this story

It takes time to make real change. That’s one thing that Stephanie Ellis has learned over the 20 years since she started working in Rockingham County Schools. But you can feel it when change is starting to take hold. That’s another thing that Ellis, the executive director for behavioral support, crisis intervention, and student safety, has learned.

It’s a feeling she’s experiencing now, two decades removed from her days as a school psychology intern and going on four years into a federal grant that is helping her district redesign what preventative and responsive mental health supports look like for students and the community.

“Sometimes we get frustrated [because] we want to move even faster,” Ellis said. “That’s the world of education now: ‘Fix it fast, move fast, let’s get this done, let’s show results.’ And the reality of it is, we’re dealing with humans. We’re dealing with little kids, big kids, preschool all the way to 12th grade. And it’s not ever going to be perfect and there’s always going to have to be adjustments.”

At a time when schools are reporting attendance and grades falling with disciplinary punishments and anxiety rising, Ellis is quick to say that Rockingham County Schools hasn’t discovered a magic antidote for all its ailments.

Thanks to a five-year grant the district received in 2018, though, the district has strengthened its mental health supports for students at the community, district, and school levels. As a result, it’s seeing better engagement among both students and educators.

“We always talk about thinking outside the box,” Ellis said. “This is like drawing a new box.”

Strengthening community partnership through federal aid

In 2018, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded a grant to North Carolina’s Departments of Public Instruction (DPI) and Health and Human Services (DHHS), providing $8.8 million for pilots focused on improving the quality and availability of treatments and rehabilitative services to reduce illness, death, and disability among children.

The federal grant is called Project Activate. Locally, it’s called Project AWARE (Advancing Wellness and Resiliency in Education).

DPI and DHHS identified three districts they felt were in good position to pilot scalable solutions: Beaufort County Schools, Cleveland County Schools, and Rockingham County Schools.

“These districts were already doing school mental health work,” said Heidi Austin, DPI’s director for Project AWARE. “Project AWARE is not the magic bullet. What it provides is the opportunity for innovation. It provides funding and provides dedicated staff on the ground and lets some pilots test different evidence-based practices, and work out how they can sustain the additional positions that they have.”

Rockingham was a natural choice as a pilot site, said Rodney Shotwell, who was superintendent there when the pilot began. He believes the district was one of the first to make significant investments in social emotional learning (SEL). He championed those efforts himself for a dozen years.

“If they’re not feeling the way that they need to feel inside, you can’t teach a kid,” Shotwell said. “And we never know what their circumstances are when they leave their house.”

Prior to Project AWARE, the district had already begun cultivating partnerships that brought community support into schools. Through Project AWARE, the district is creating partnerships to ensure supports don’t end at the doors of the school building.

At school, Shotwell said, students could expect breakfast at 7:30 a.m., P.E. at 10 a.m., and lunch at 12:15 p.m. That structure and routine isn’t always present outside of the building.

“When they leave us and they get on that bus or they get in that car, it’s chaotic,” he said. “And we don’t know what’s going to happen. And they don’t know what’s going to happen. The fact that we’re getting in tune with that on a much larger scale, I think is such a big piece of what’s going to make us so very successful.”

This is what it looks like

The district’s Handle With Care initiative is a prime example of partnering with the greater community to support kids.

Chrissy Griffin, director of the Family Justice Center in Reidsville, works with people affected by domestic violence and sexual assault. Sometimes her clients are parents. Other times, they are children. When a child was involved, she’d ask the parent if the school was aware of what was happening.

“Because the child can be in fight, flight, or freeze at school,” she said.

Typically, the response she got was that the parent hadn’t thought about involving the school. It gave Griffin an idea.

She had studied adverse childhood experiences research. She knew the importance of putting at least one adult confidant in a child’s life. It can’t always be the parent, she said, so she wondered how to better involve school personnel. How could folks outside the school building give educators a head’s up when a student might need some extra love?

The solution is a mobile app that sends a non-detailed notification to school and community partners. It lets everyone know that something’s up with a student, but it doesn’t share personal information.

For example, if a child is in a car accident, first responders can send a “Handle With Care” notification. The notification, delivered via the app, goes to community leaders — the schools included.

“It doesn’t give any details and they don’t ask any other details,” Griffin said. “It’s just the child and the student is the [focus] for that day. And that may be that they need more food, they need some more rest time, or they need to retake a test or something.”

At Stoneville Elementary, where the app was first piloted, the school has seen it work several times. Once, a student showed up the day after their parent attempted suicide. Another time, a student’s home was hit during a drive-by shooting. The child showed up for school the next day.

“We would have known nothing had it not been for Handle With Care,” Principal Kasie Pruitt said. “So it has really been a positive, proactive outreach in our community and in our school, and we have really felt like it has created a lot of positive relationships with our families.”

Once the app notifies schools that a student may need extra love, educators have a bevy of processes and tools that are now in place to get the student the support he or she needs.

Those tools exist on both the district and school levels.

Reimagining mental health teams and classroom lessons

Rockingham County Schools now has a district-wide Behavioral Support District Integrated Response Team guided by four behavioral support specialists. The grant paid for three of those positions. The local school board added another behavioral support specialist.

“I have seen the need in the schools for this,” said Vice Chair Vicky Alston, who is a former teacher and principal. “Because you have children from all aspects of life that come into your building, and you know something’s going on but you don’t know exactly what and how to pull it out of them. … So I know the need for these folks in the school, and what advantage it is to have them with you.”

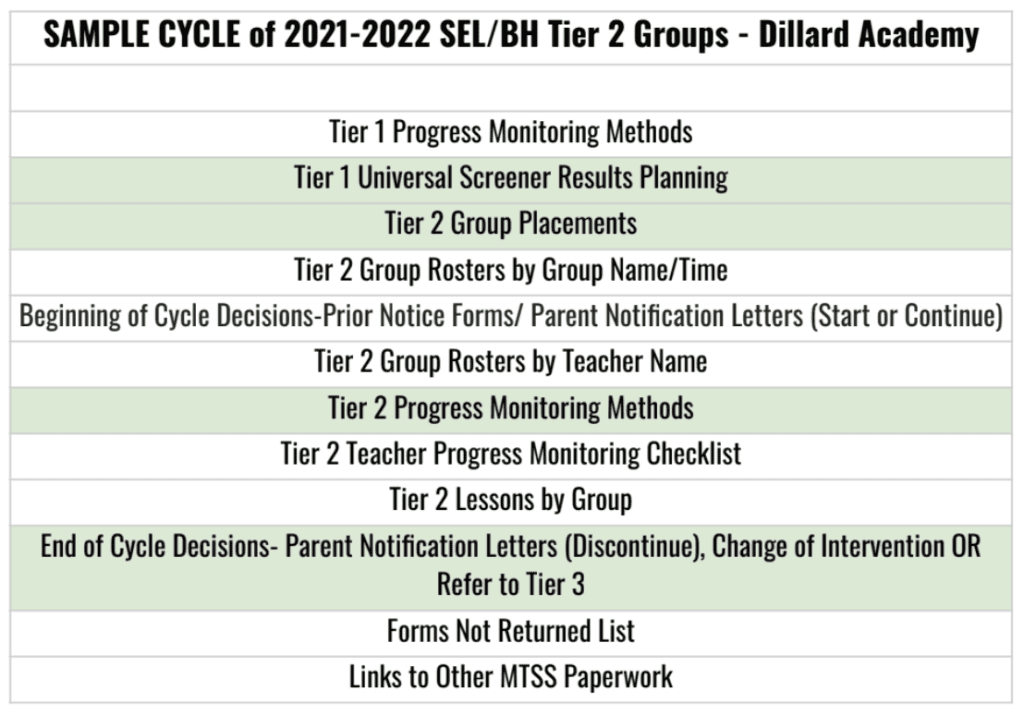

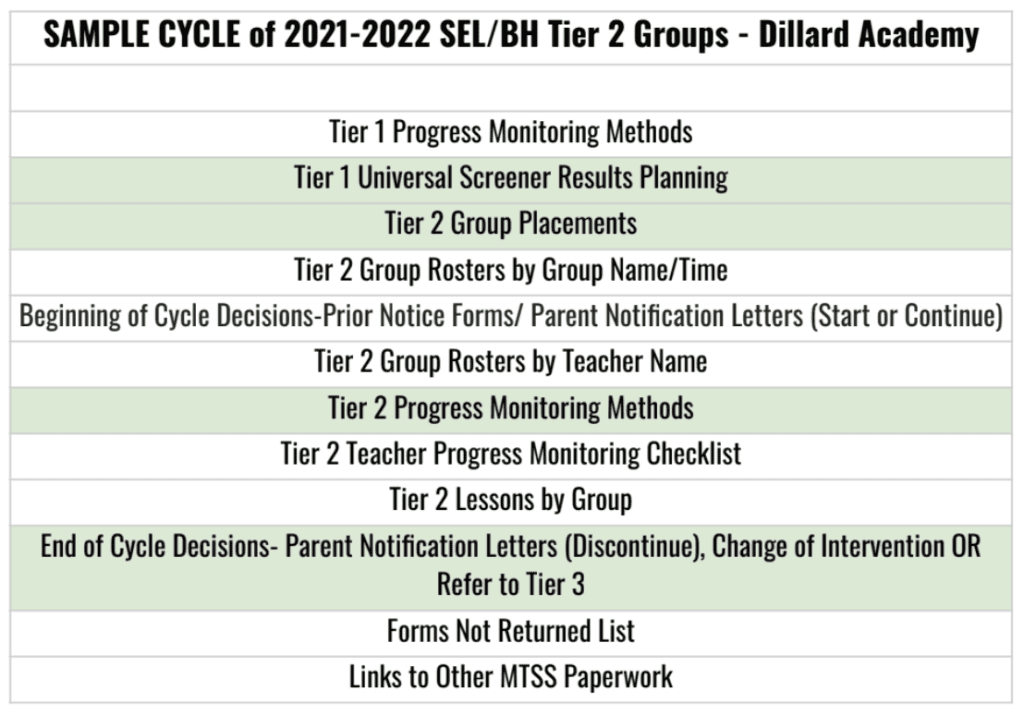

Every school in the district has its own team which meets regularly and runs through the same agenda to ensure close monitoring for students in need of support.

“Our whole purpose in these mental health teams is really to remove barriers for kids to access their education,” Ellis said. “To have, really, their best life.”

The district-level leadership team and synchronized processes are critical to providing equitable services, Ellis said.

“We wanted students to have the same services, no matter where they were,” she said. “We didn’t want zip code to determine what kinds of services that they got.”

At Central Elementary School, the day begins with a 20-minute SEL meeting, because “our team recognizes that a daily focus on social and emotional needs of our students sets them up for better success,” said principal Jane Frazier.

The school focused on growth during the summer acceleration academy following the 2020-21 hybrid remote/in-person school year. There was a lot of academic ground teachers needed to cover with students, but the schools’ SEL screening showed students were as far behind in growth mindset, resiliency, and emotional regulation as they were in math and reading.

So the teachers integrated SEL lessons into academic instruction over the summer.

“And so the teachers that were teaching in the summer program were saying things like, ‘You won’t believe how great these lessons are, you won’t believe the conversations our kids are having,’ and they were just seeing a lot of growth from that,” Frazier said. “They wanted to see it happen across the whole student body.”

The school developed an action plan for incorporating SEL into classes daily. The instructional coach created a four-hour, self-paced professional development for staff to complete over the summer and created two weeks of SEL lessons for staff to use with students when school started up.

One day, Frazier was covering a class in the media center because a teacher was out sick. The students were making crafts and she marveled at their creativity.

“I said to one, you know, this is so creative, I don’t think I could have thought of something like that,” Frazier recalled. “And he said, ‘Whoa, Ms. Frazier, you could have done this. You got to have a growth mindset.’ It has had a big impact.”

In the final year of the grant, buy-in is high

Walk into any Rockingham County Schools building and you’ll see evidence of a culture shift. You’ll see it in classrooms and conference rooms, alike, where both classes and meetings start with a welcome, focus on continuous engagement, and end with an optimistic closure.

“Every single one of our schools in Rockingham County implement those strategies,” Ellis said.

Perhaps the best evidence that things are working is that adults across the county want to see even more investment in these efforts.

In schools, educators are more bought-in. Tina Whitten, an instructional coach at Dillard Academy, is seeing the SEL lessons take root there, too. As someone who focuses on coaching teachers in academic instruction, she wasn’t excited when she first heard that every school in the district had to hold mental health team meetings and incorporate social emotional lessons to the day.

“Here’s one more meeting,” she thought. “Really, do we need to do this?”

But then she saw it in action. She saw the impact it had on students who weren’t concentrating in class because they were thinking of other things. No amount of academic instructional coaching would reach those kids in those moments.

“They don’t care how to indent a paragraph and they don’t care how to multiply by the reciprocal to divide a fraction,” she said. “They’re worried about, did my mom get arrested in the car pool line today, which we have had happen. They’re thinking, did we have a student who died in a fire.

“So because of the lens that I had with assessments and data and who’s on grade level and who’s not, and we’ve got to get them on grade level, we’ve got to get this intervention in place, where’s the resource, what’s the strategy, what’s the best practice – I had to change that a lot when we realized sometimes we have to start dealing with social and emotional needs of children first.”

Schools are now so in tune with student mental and emotional needs, there’s a clamoring demand for specialists’ time. The grant also helped the district bring its ratio of specialized instructional support personnel to students closer to nationally recommended standards.

“And we really get creative with our time, but it’s not enough of us,” said Paula, a district behavioral support specialist. “I’m assigned to three schools right now, but while I’m here with two of my schools my third one is saying, ‘Hey, what time will you be done because we want you to see this kid here today.’ And you know, what can we do?”

The board is taking notice. Funding is a challenge, but they know the need is there.

“They need to be in the school all the time, not one day or two days in another school,” Alston said. “They need to be stationed at one school and stay there throughout the year, to be able to do their job.”

That kind of buy-in isn’t universal. In some counties, school boards have cut mental health support and parents are demanding that SEL stay out of schools. But in Rockingham, the grant has provided the district an opportunity to demonstrate what’s possible when schools invest in mental health.

That investment, Alston says, is made in more ways than just through money. It’s demonstrated through the leadership capital the district provides via Ellis. She’s grown in the district from intern to directing an entire division, and it’s her passion and vision that are guiding the grant efforts through Project AWARE.

“This lady right here, she is a blessing to Rockingham County Schools,” Alston said. “She has nothing [at heart] but the best interest of the children that we all serve. Without her, this would not be possible.”

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article misidentified the name of Stoneville Elementary School It has been fixed.