It’s only in the quiet moments that I am able to hear my own heartbeat. The sturdy drum right at the center of my being. The pulse that unifies all that dwell on this pale blue dot.

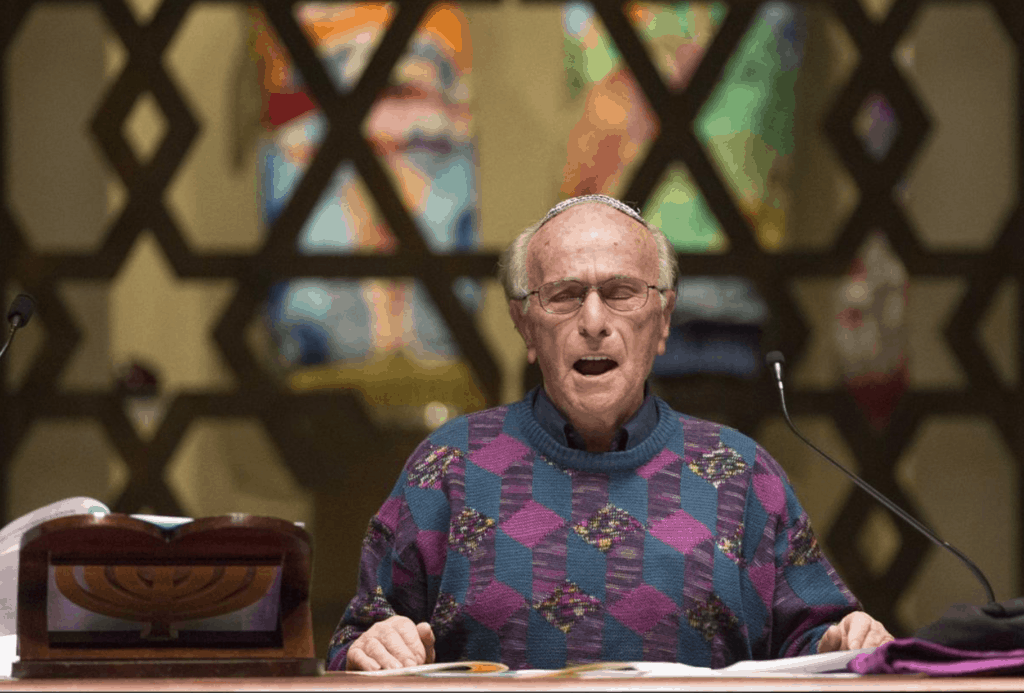

Two days before George Floyd died, Hank Brodt passed away. He was one of the few Holocaust survivors that belonged to our temple. More than that, he was a friend and a reminder of the resiliency of the human spirit. He survived five Nazi concentration camps. His passing hit me hard and our community even harder. His story taught me the importance of speaking up. I think that’s why I needed to process this current devastation through a Jewish lens.

How did we forget this — this thread of life that lives in every single one of our bodies? How did we become so numb to the fragility of human life? How did we let division sink its insidious claws into our skin so deep we can’t even recognize the light in another’s eyes? How can we not look? Have we forgotten how to see? Have we forgotten how to hear? The cries of our neighbors? The screams in broad daylight? There is so much hurt here. There is so much pain. There are lifetimes of work to be done.

They can’t breathe. We can’t expect them to when we take up all the air.

Every bone in my body aches to speak out, to speak up for the horrific injustice that took place last week. For the horrific injustices that have become so common that many people won’t even stop scrolling their phones to read the names of the deceased.

But each time I’ve come close to sharing my thoughts, I stop.

I don’t have the answers. I won’t pretend to. But I will continue to carry the weight of these questions. To wrestle with solutions. To drag our collective ego out of the dark cave it hides in. To continuously process my privilege and use it to contribute to the common good. I want to play my part. I want to remain awake even when it’s hard, especially when it’s hard. I will not be blind to the truth of this world we have created.

Thousands of years ago, Rabbi Hillel, one of the most notable Jewish sages, asked these questions —

“If I am not for myself, then who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, then what am I? And if not now, when?”

Millions of people have lived and died since these words were written. Empires were created and destroyed. The dark night has come and come again, and we are still learning.

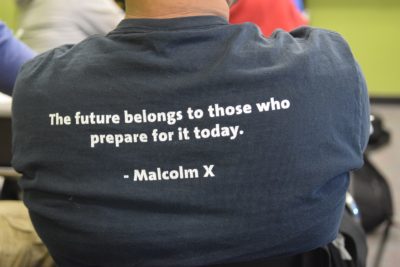

This quote is commonplace in Jewish circles. You’ll hear it recited by wide eyed 17-year-olds in confirmation speeches (cough cough like my own), printed on the backs of T-shirts, and tattooed on Jewish millennials looking to make a statement.

What’s even more commonplace, though, is the very act of asking questions, of continuous self-reflection, of taking action on our values.

After surviving the Holocaust, in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, Victor Frankl wrote:

“No man should judge unless he asks himself in absolute honesty whether in a similar situation he might not have done the same.”

It is not our place to judge behavior coming from a deep pain we will never know. A deep pain we were part of creating and upholding.

Decades later, in 1965, Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote:

“When I marched in Selma I felt my legs were praying.”

I find this notion of praying with your legs especially relevant today. I wonder what these wise people would think of social media, about the silos we have created digitally, about the division we stoke with tweets, likes, and comments. Recently I’ve been especially struggling with the increased focus on social media activism. Particularly the presumption made by people who claim that if you’re not sharing the same three graphics that they are, then you’re not an ally.

This challenges me for several reasons:

- Besides raising awareness, which is critically important, what does posting on social media really do?

- Are we posting because we truly care or just because we want to appear to? Is it just another form of social validation that these online spaces have magnified in our lives?

- What about the people who don’t have social media? I have a good friend who works day in and day out to own up to her own implicit biases. She also works in a job that is helping to dismantle racism in our institutions. This year she is reading books only by Black women. She doesn’t use social media and hasn’t posted about any of this once. Does that mean what she’s doing doesn’t matter?

Let me be clear and say that I don’t think posting on social media is wrong. I think it can be helpful in many ways and has helped spread awareness and spark change. I just want to challenge how we think about what it means to make a difference and if our idea of that is sharing a graphic and criticizing people who don’t, I think we can dig deeper. I think we can do better.

In addition to all of these reasons, the one question I keep coming back to is: how can I do more? We all know posting a graphic isn’t enough. I worry that many of us, myself included, fall into the social media trap of needing to feel validated for the work that we’re doing instead of actually getting our hands dirty and doing the work.

If we really want to Tikkun Olam (Repair the World), we’re going to need to do a whole lot more than tweet about it. I commend the people who are putting their phones down, engaging in difficult conversations, walking in solidarity, and lending a hand wherever it is needed.

We can do better. We must do better. The time to start was years ago. The time to restart is now.

Recommended reading