This year, EdNC will take an in-depth look at North Carolina through a variety of lenses, including the lived realities of adolescents in rural counties.

We think North Carolina needs to move away from one-size-fits-all solutions and move towards political, policy, and philanthropic strategies that take into account the very different needs of urban areas, suburban areas, rural counties with a metro hub, clusters of similarly-situated rural counties, and rural counties with no urban cluster. We want you to weigh in.

“This is an issue about people. Rural or urban, we have the same dreams, same hopes, same desires. We are not fundamentally different. But the challenge is how to get people to talk about common issues. The rhetoric is not there. That is what we need to grow together.” Dan Glickman, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, 1995-2001, speaking in North Carolina on February 6

What counts as rural in the 21st century? Ferrel Guillory says that there are about 100 ways to define rural, and then he smiles, and says he is only exaggerating by about 10.

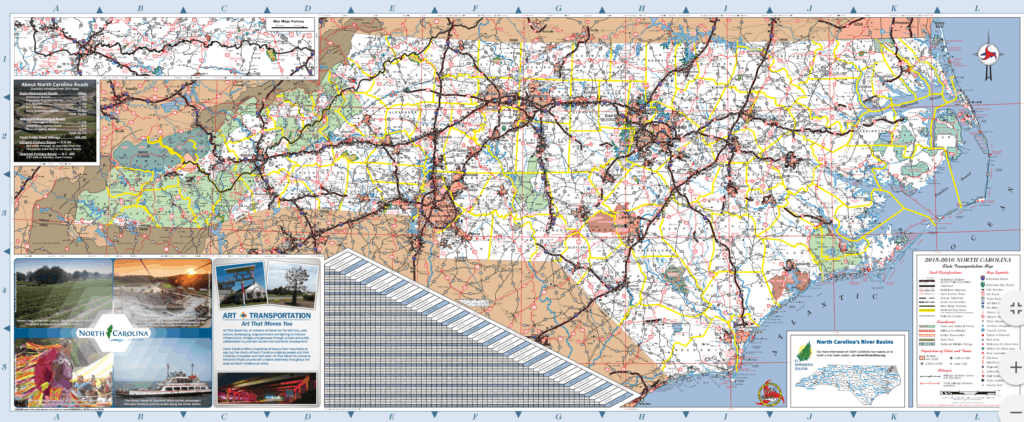

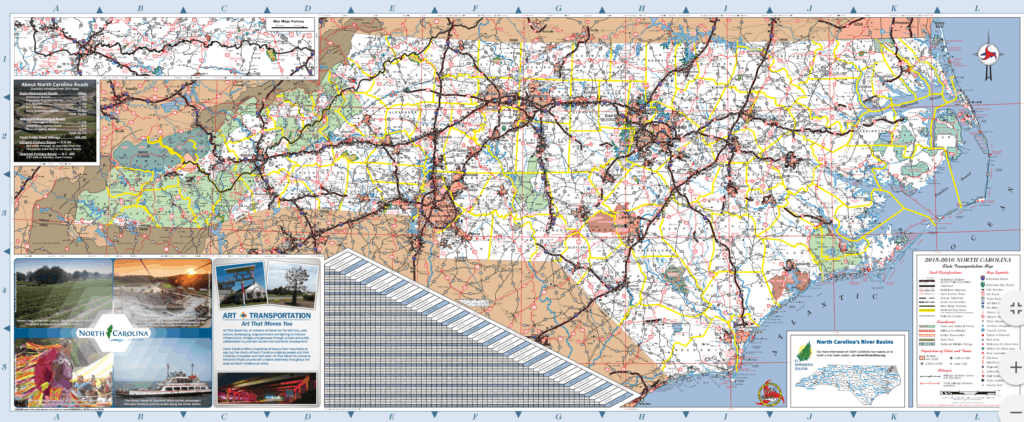

As you drive our urban crescent along I-40 and I-85 from Raleigh to Charlotte, it is easy to forget just how rural North Carolina is. “Among the 10 most populous states, North Carolina has the largest proportion of individuals living in rural areas. In fact, North Carolina’s rural population is larger than that of any other state except for Texas,” writes Rebecca Tippett with Carolina Demography.

John Hood, president of the John William Pope Foundation, writes, “Most North Carolinians still live in places other than the largest cities. Most of them like where they live, and the lives that they live there.”

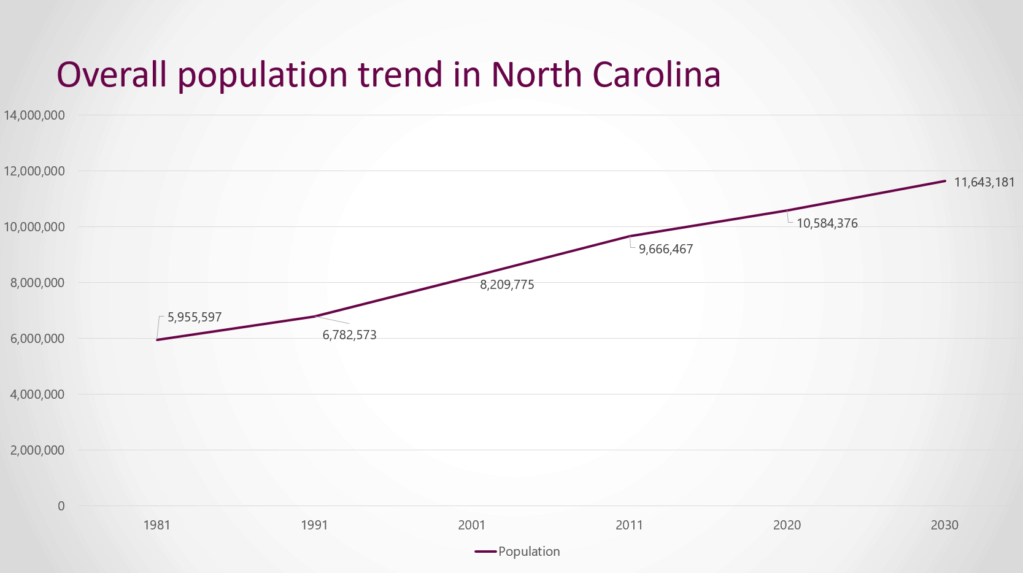

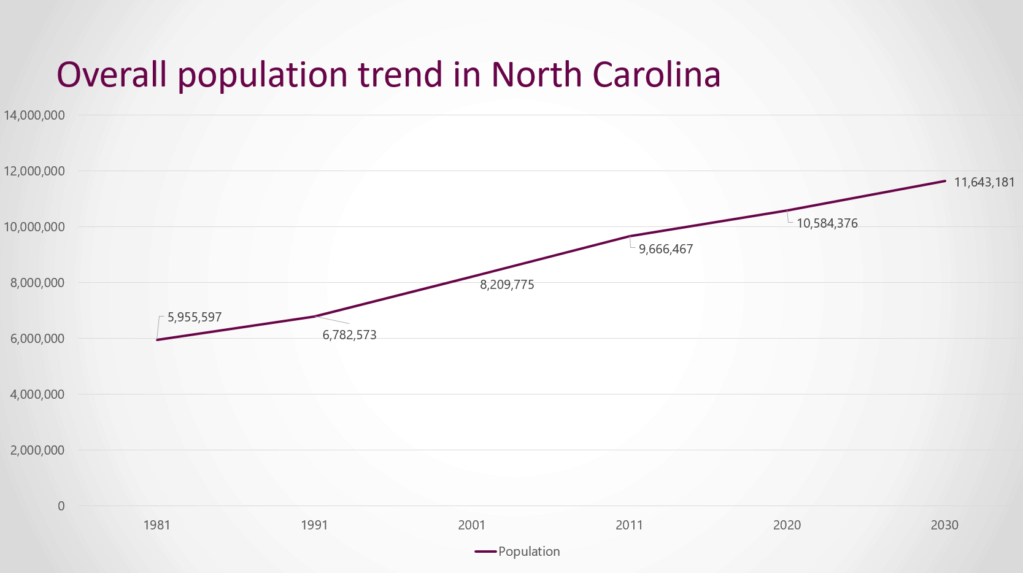

Over 50 years, between 1980 and 2030, the population of North Carolina will almost double rising from just under 6 million to almost 12 million.1

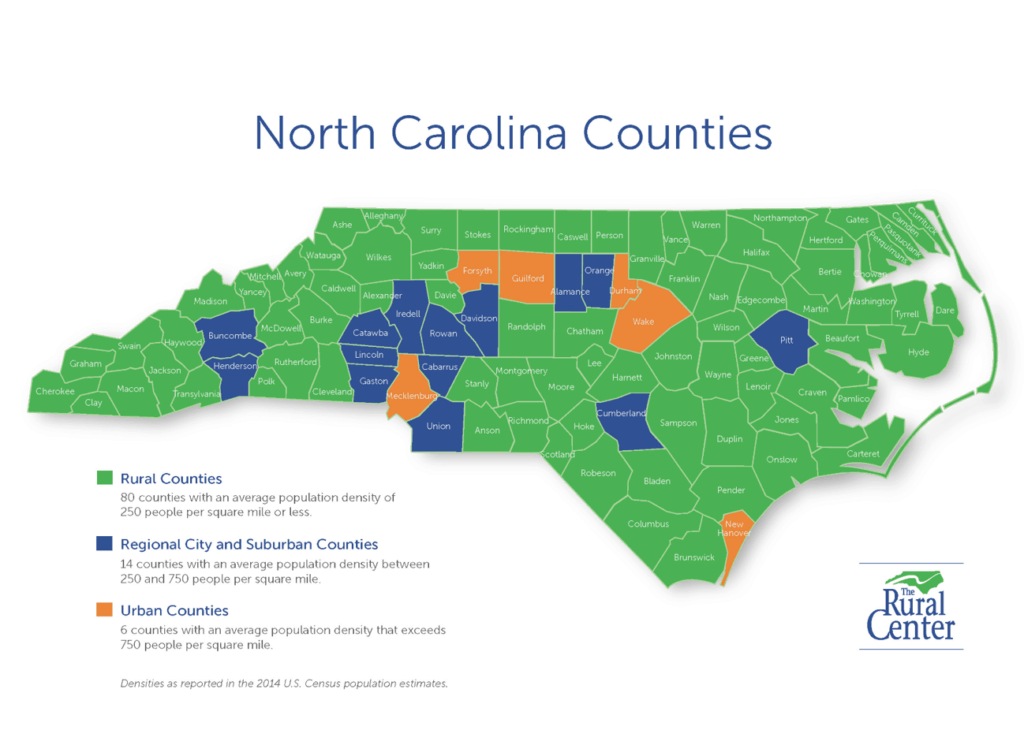

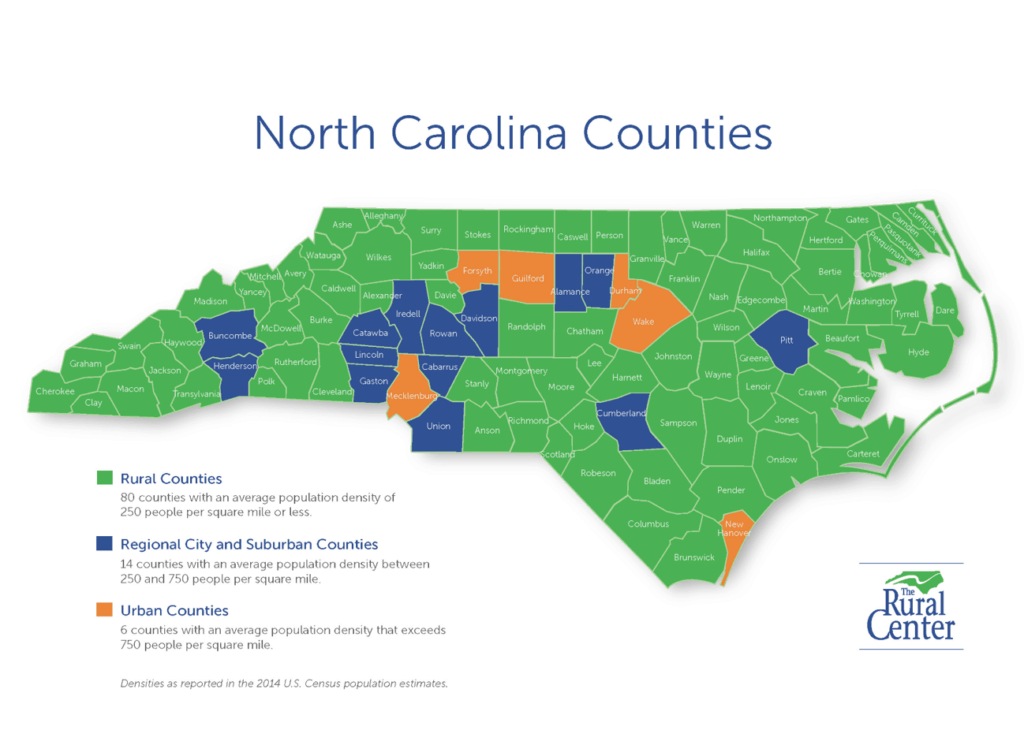

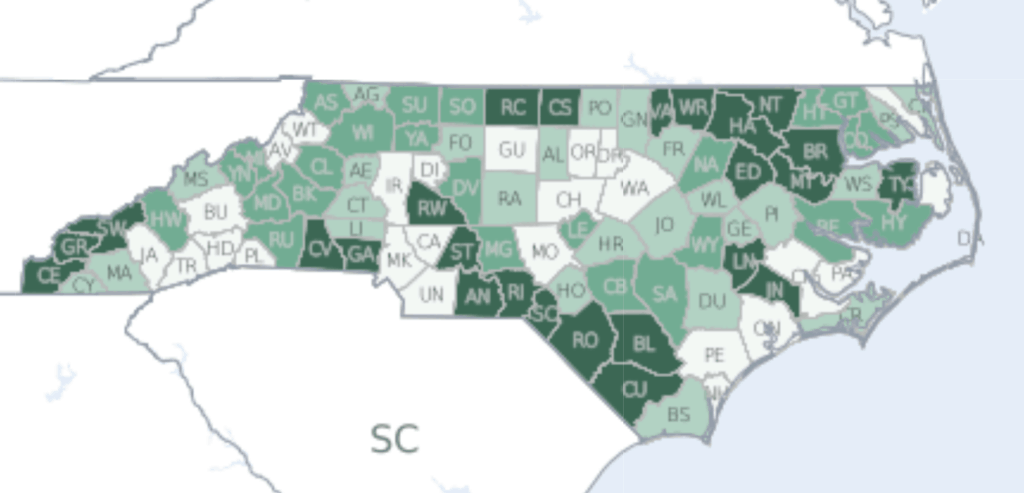

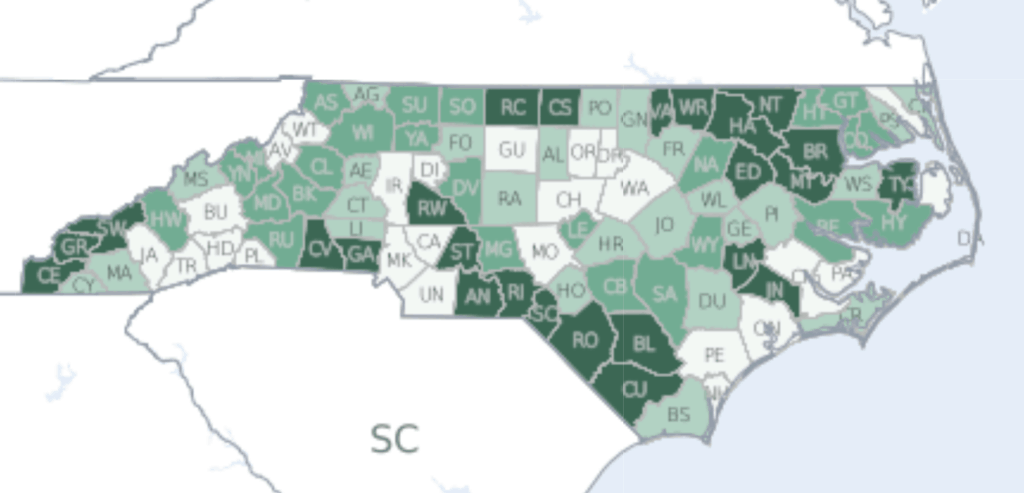

Across North Carolina, we have 100 counties. North Carolina is fortunate to have the N.C. Rural Center, identifying rural issues, rural voices, and rural solutions. The Rural Center uses density to assess which counties are rural, finding that we have six urban counties with density that exceeds 750 people per square mile, 14 regional city/suburban counties with density between 250 and 750 people per square mile, and 80 rural counties with density of 250 people per square mile or less.

In meetings with thought leaders across the state, we have started the process of thinking through ways to get a better handle on the differences among those 80 rural green counties.

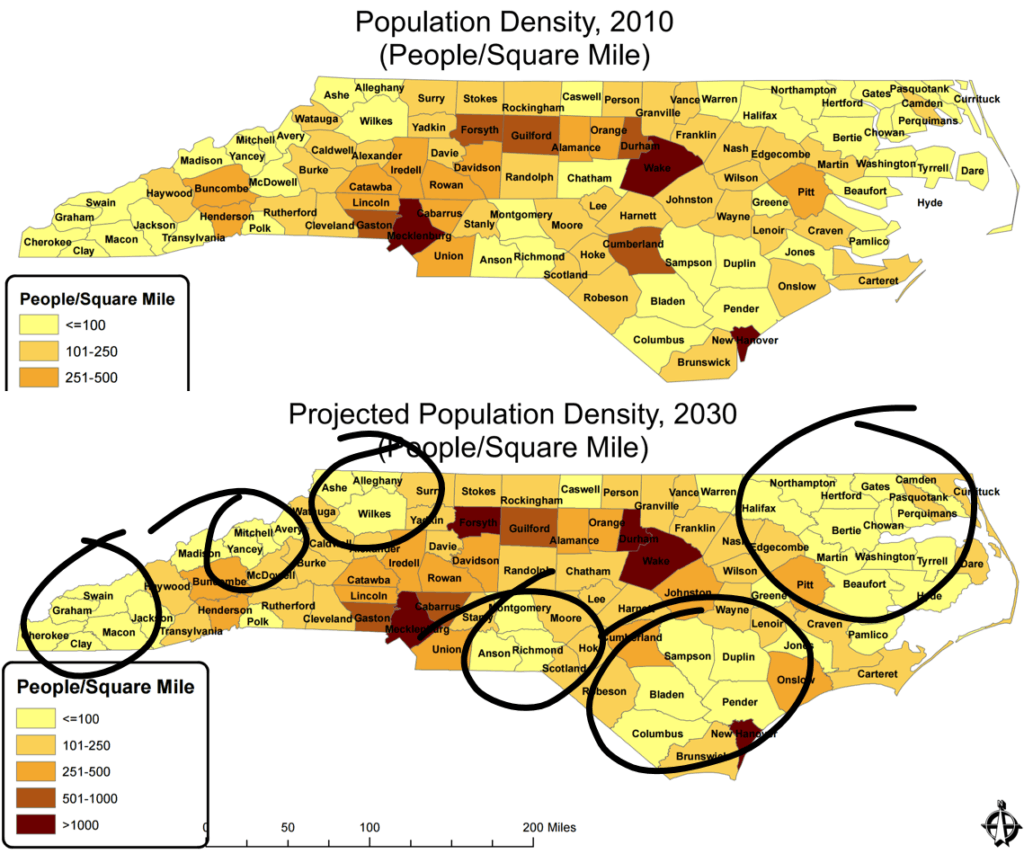

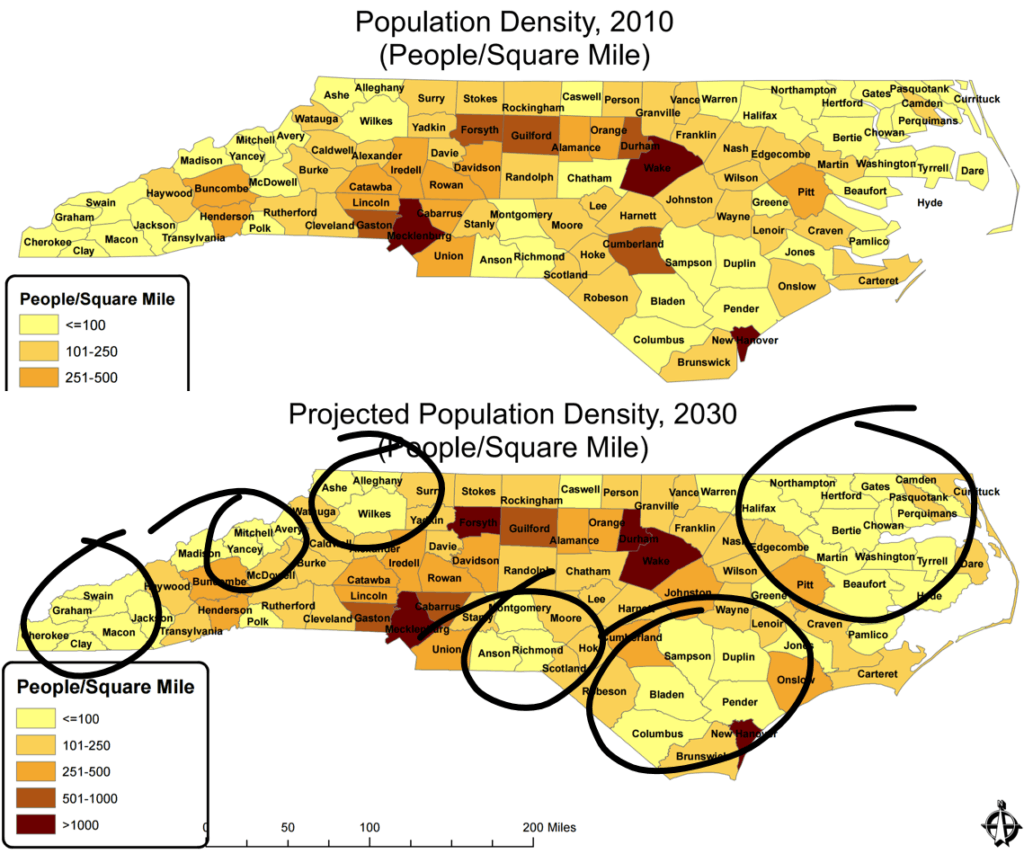

These more nuanced maps from the Office of State Budget and Management compare population density in 2010 and 2030. Note the number of yellow counties with 100 people per square mile or less in each map. Note the clustering of yellow counties — and think about the other maps in this article relative to the circled areas.

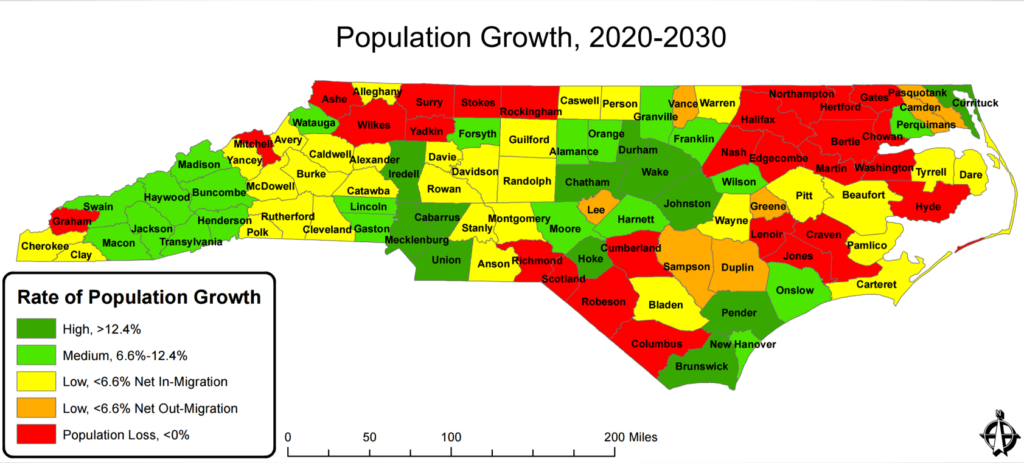

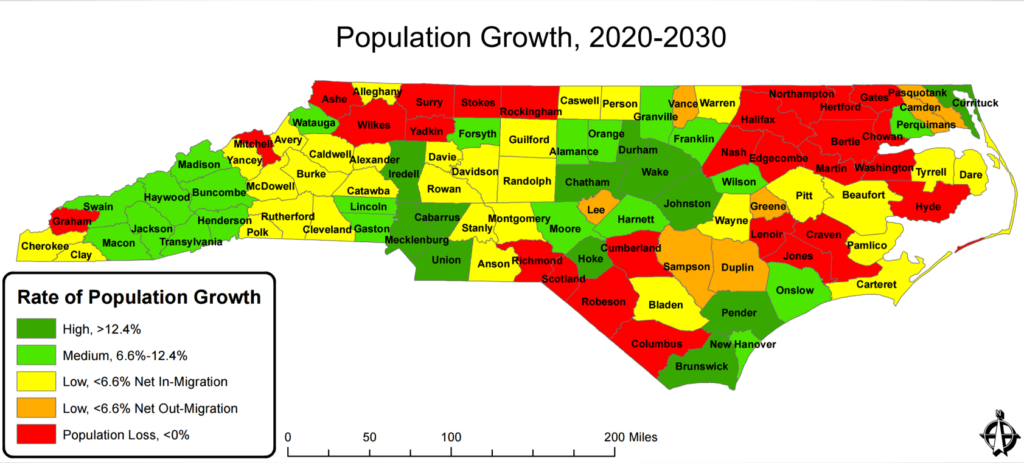

This map, also by OSBM, is a longer range map of population growth so you can see the counties that will be gaining and losing population over time.

These maps by the UNC Program on Public Life illustrate North Carolina’s evolution from an agrarian state to a metropolitan state by showing the population growth from 1900 to 2030. Each dot represents 1,000 people. Guess what the biggest city in North Carolina was in 1900? Wilmington — because it was our port city.

Factors driving density and growth

As we look at these maps, we see four factors driving population density and growth: proximity to municipalities, proximity to natural resources, proximity to an institution of higher education, and proximity to an interstate highway. These factors can be economic drivers.

In the North Carolina Visitors Network Travel and Adventure Guide, Greene County puts forth this description: “Located in beautiful eastern North Carolina in the middle of the coastal plain, Greene County is bordered by Goldsboro, Greenville, Kinston and Wilson making major shopping malls and rich cultural activities only a 15-25 minute drive.” Access to municipalities matters.

Our beaches, our mountains, and now our land for solar farms also can drive density and growth. North Carolina is now the 3rd largest solar energy producer in the country.

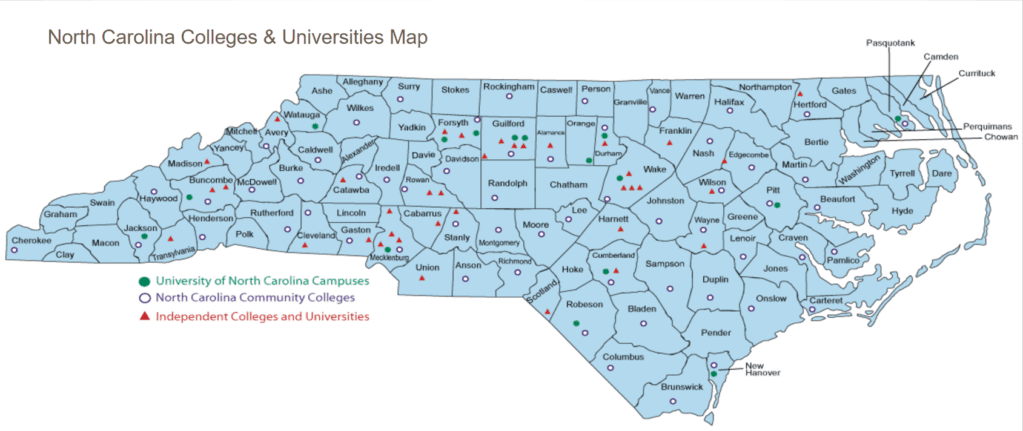

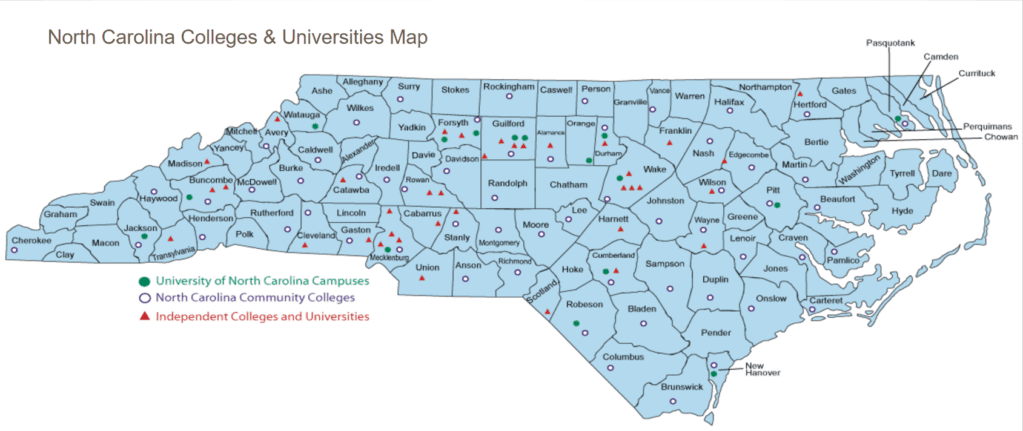

This map shows where our institutions of higher education are located. Note which counties don’t have a community college, private college/university, or UNC campus.

Some counties are able to build local economies around the institutions of higher education.

North Carolina has about 1,300 miles of Interstate Highways that can serve as corridors of prosperity.

An even more nuanced look…

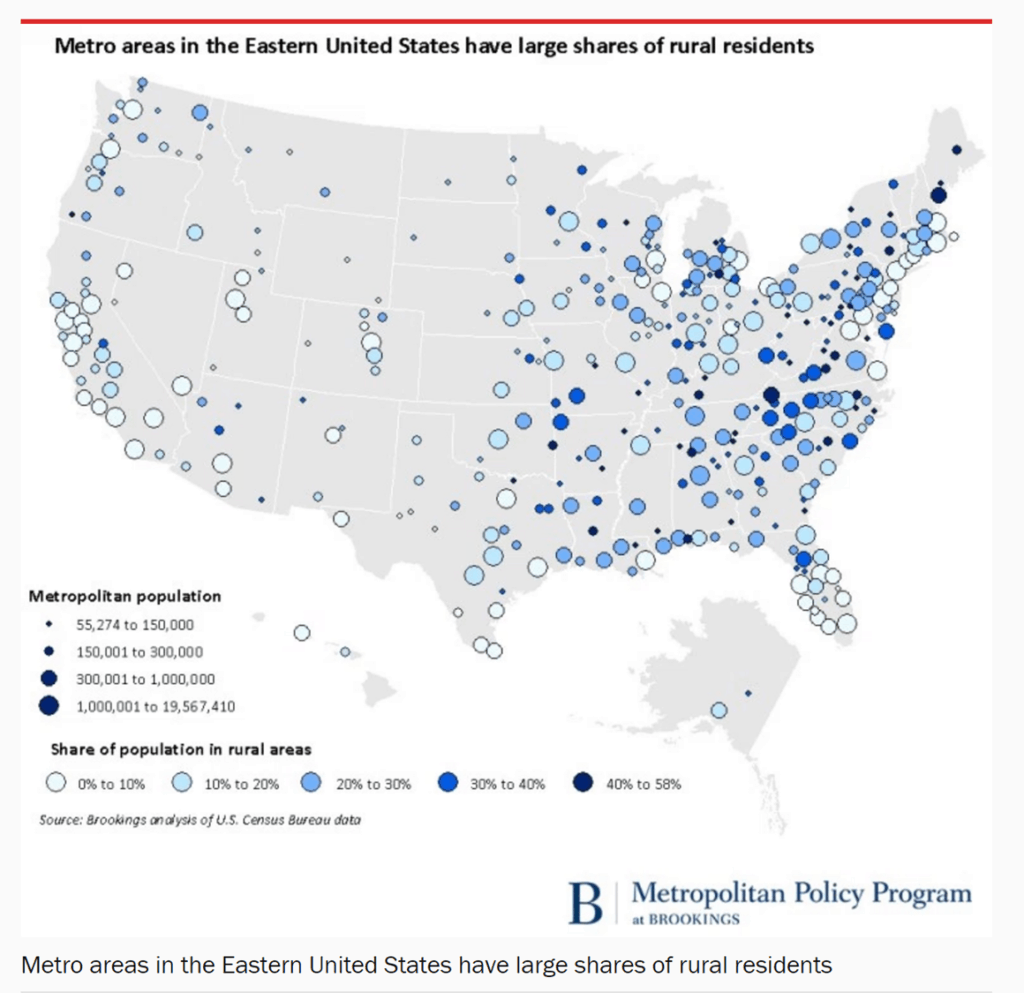

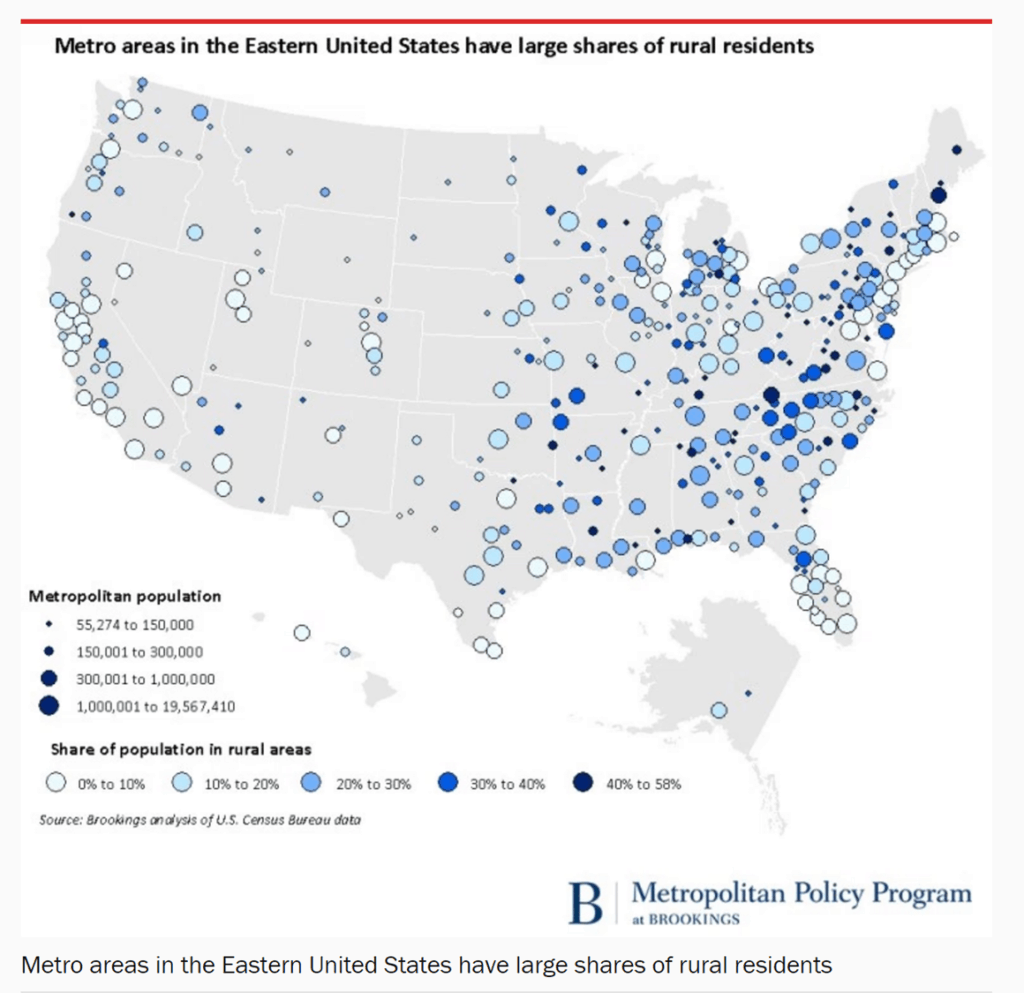

Increasingly, rural residents in North Carolina live in metro areas. For instance, three in 10 residents of the Winston-Salem metro area live in a rural community, according to Brookings.

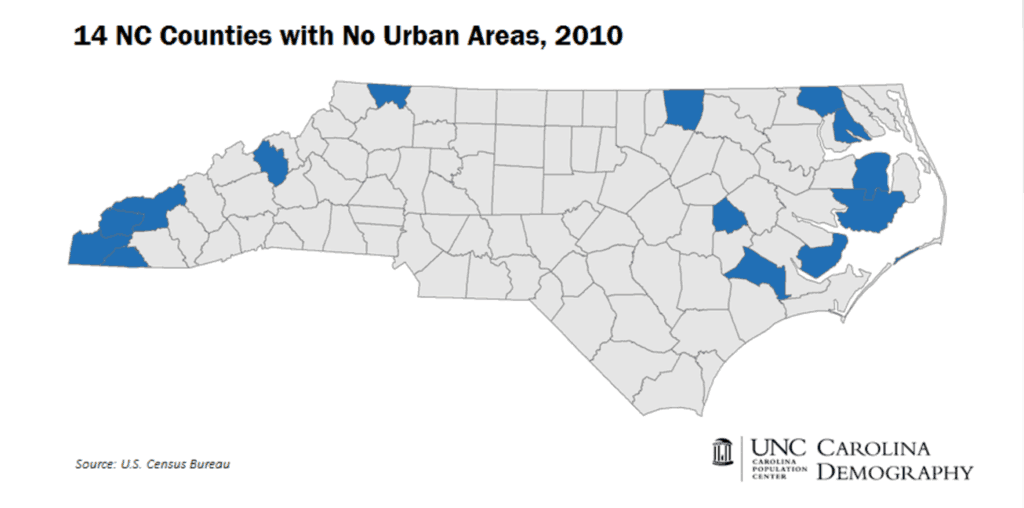

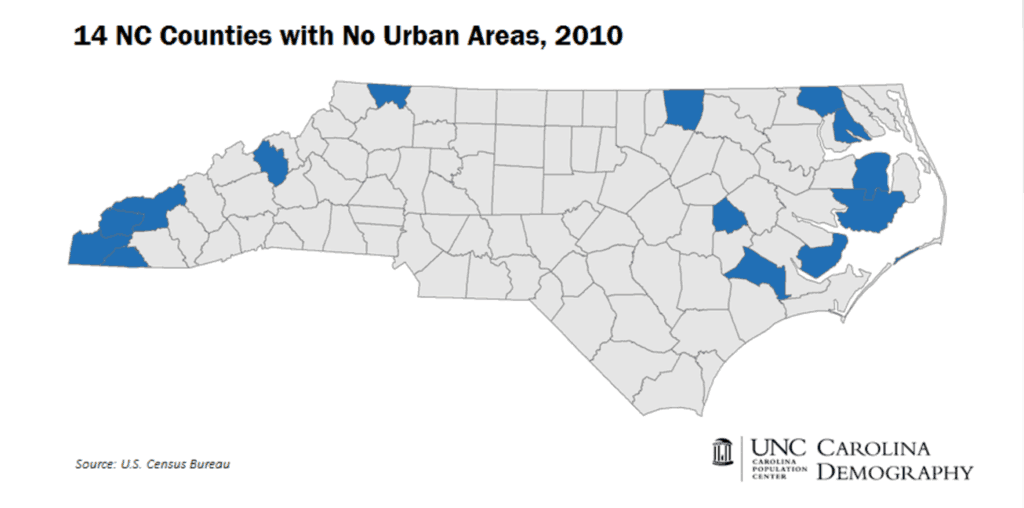

The U.S. Census Bureau uses two definitions of urban area: urbanized areas of 50,000 or more people and urban clusters of between 2,500 and 50,000 people. Carolina Demography finds that 14 counties across North Carolina have no urban area.

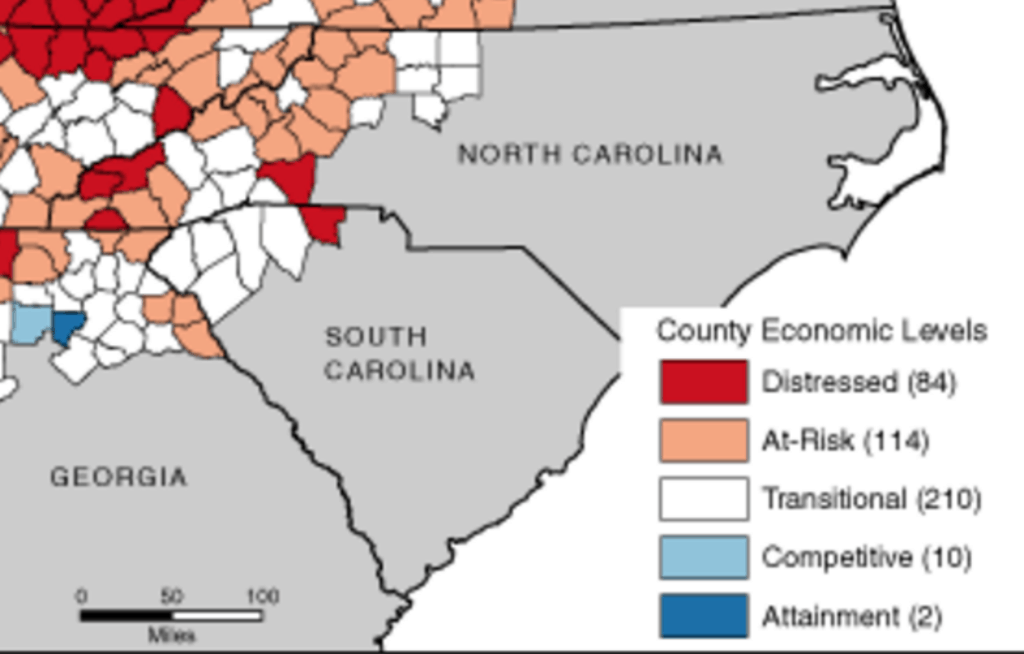

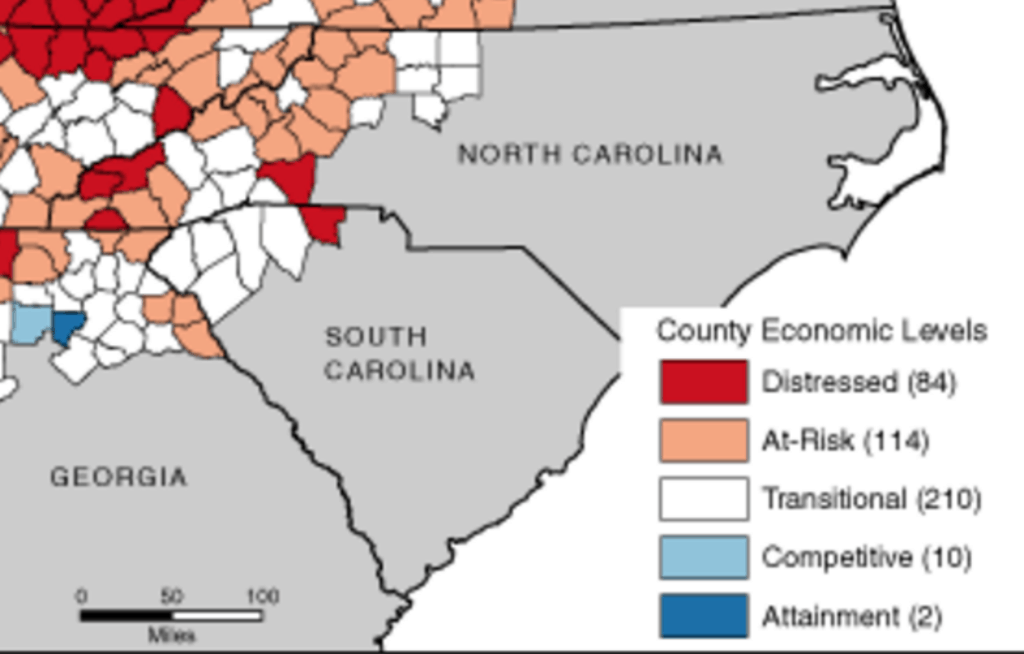

Each year, the Appalachian Regional Commission maps counties out west with economic distress. What would a statewide map of distress look like?

Impact on opportunity

These maps led us to think about how location impacts on opportunity. We wondered…

Where are our jobs? What are our jobs? Which counties have educational disparities? Where are our best schools? What is the impact of school choice? Which counties have health disparities? How does the aging of our population impact rural counties? And does it matter if the county is red, blue, or purple politically?

Jobs

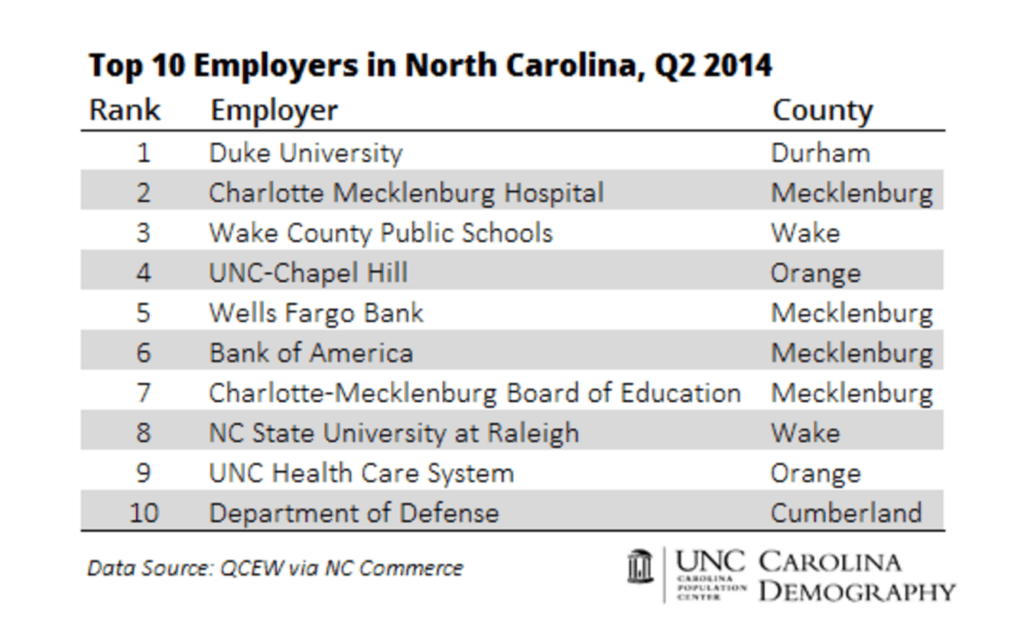

It often surprises people that Duke University and the hospital is the top employer in North Carolina. It doesn’t usually surprise people that our top employers are not located in rural areas anymore, according to Carolina Demography.

This GIF shows the top employers in counties across the state. In rural counties built around the military or agriculture, the economy is at odds with density because big wide open spaces are needed, and yet those counties need better ways to build the systems that density supports. Note that in 59 counties across North Carolina our public schools are the top employer — a point our state has not confronted in debates about school choice.

Sam Houston, the president and CEO of the North Carolina Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education Center says, “We don’t want or need to ‘bring back’ jobs that have been lost. Those jobs are gone. We need new jobs for our 21st century workers.”

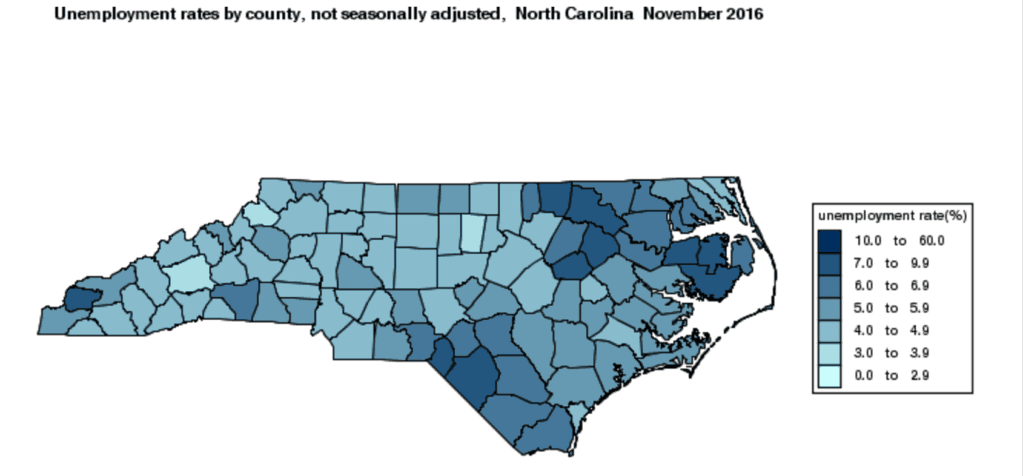

In this map you can see the unemployment rate by county in November 2016, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

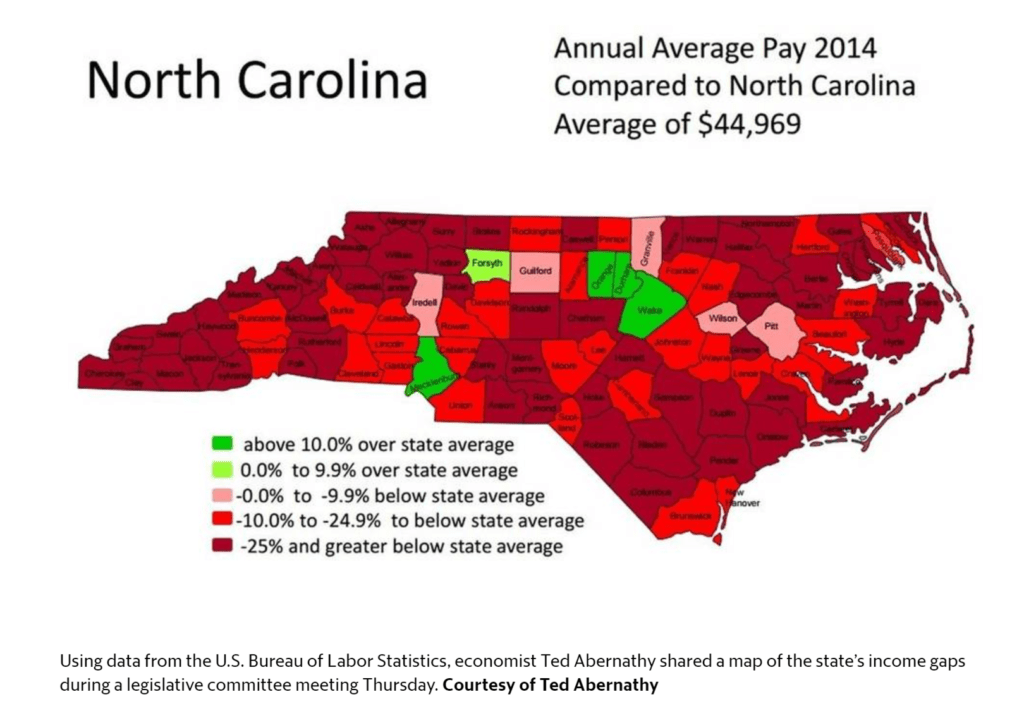

Economist Ted Abernathy prepared this map for a legislative committee meeting showing average annual pay by county in 2014.

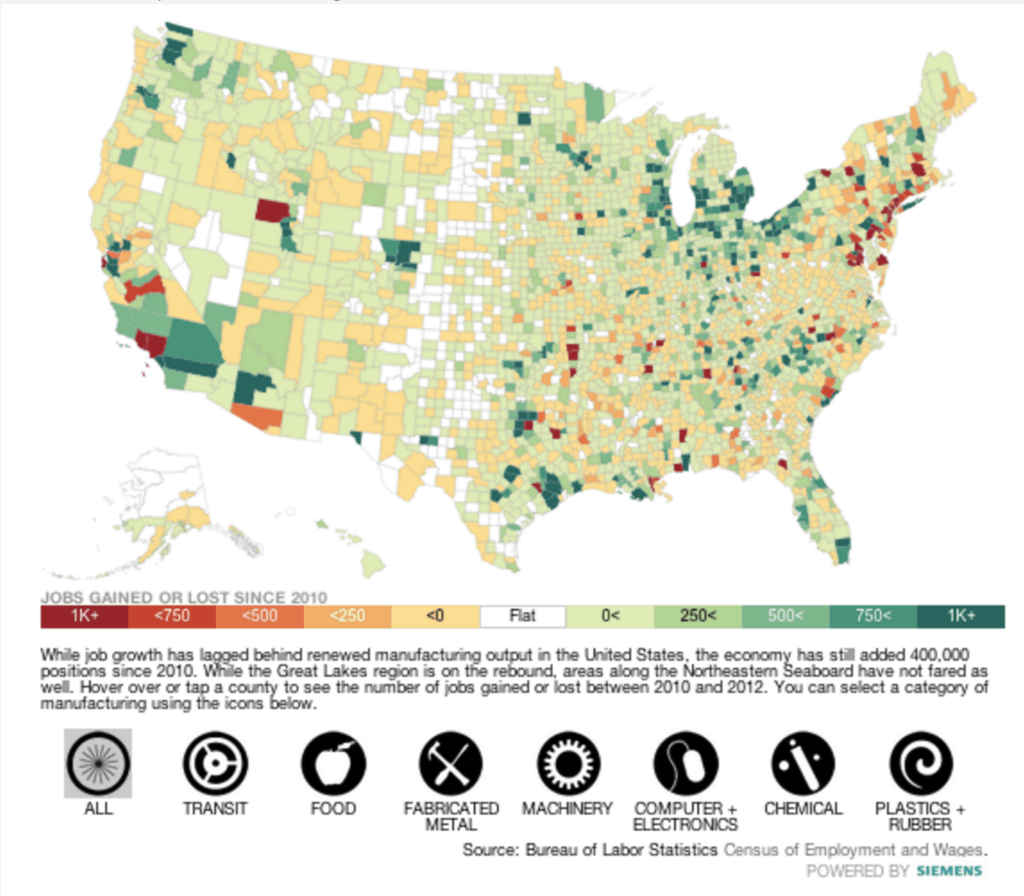

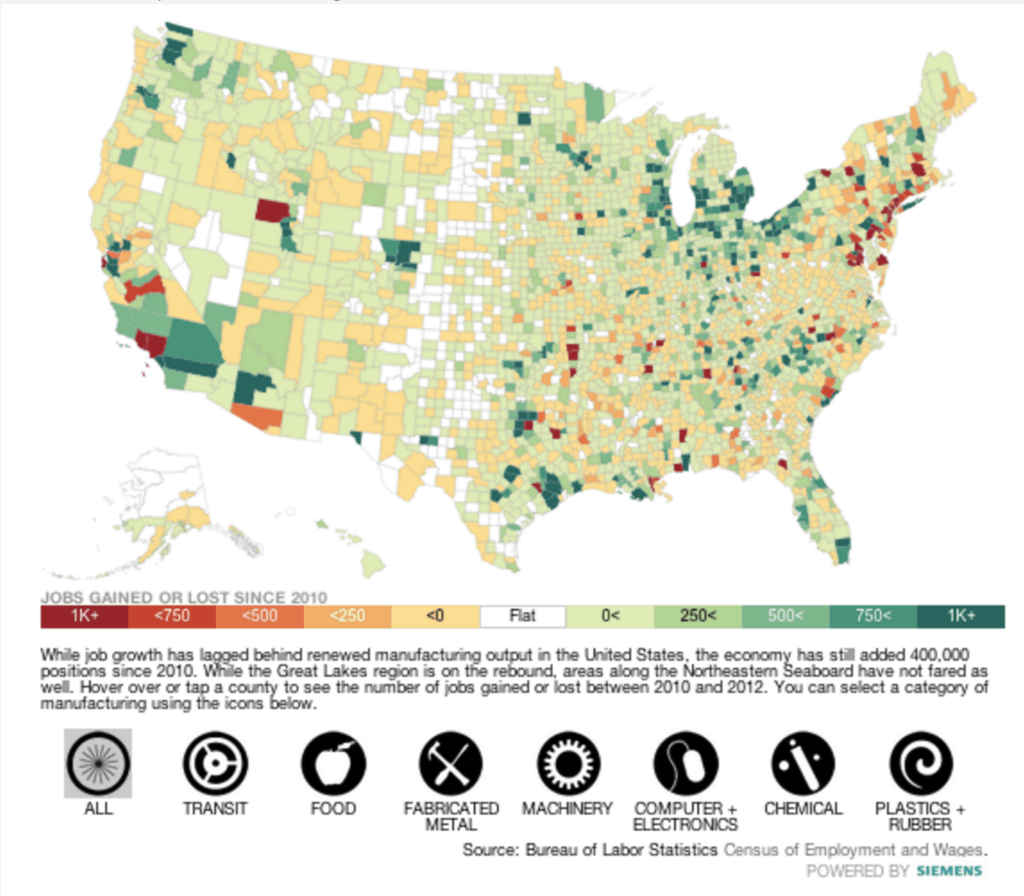

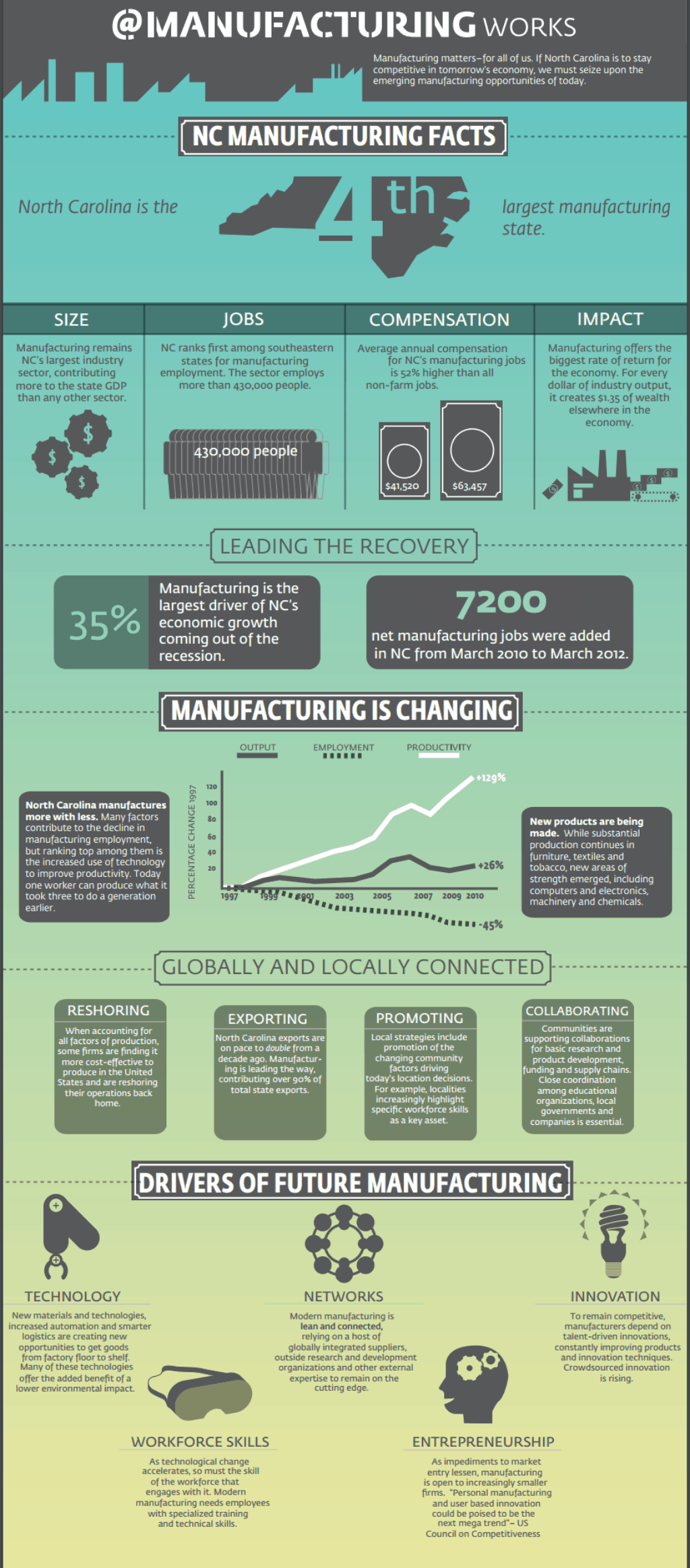

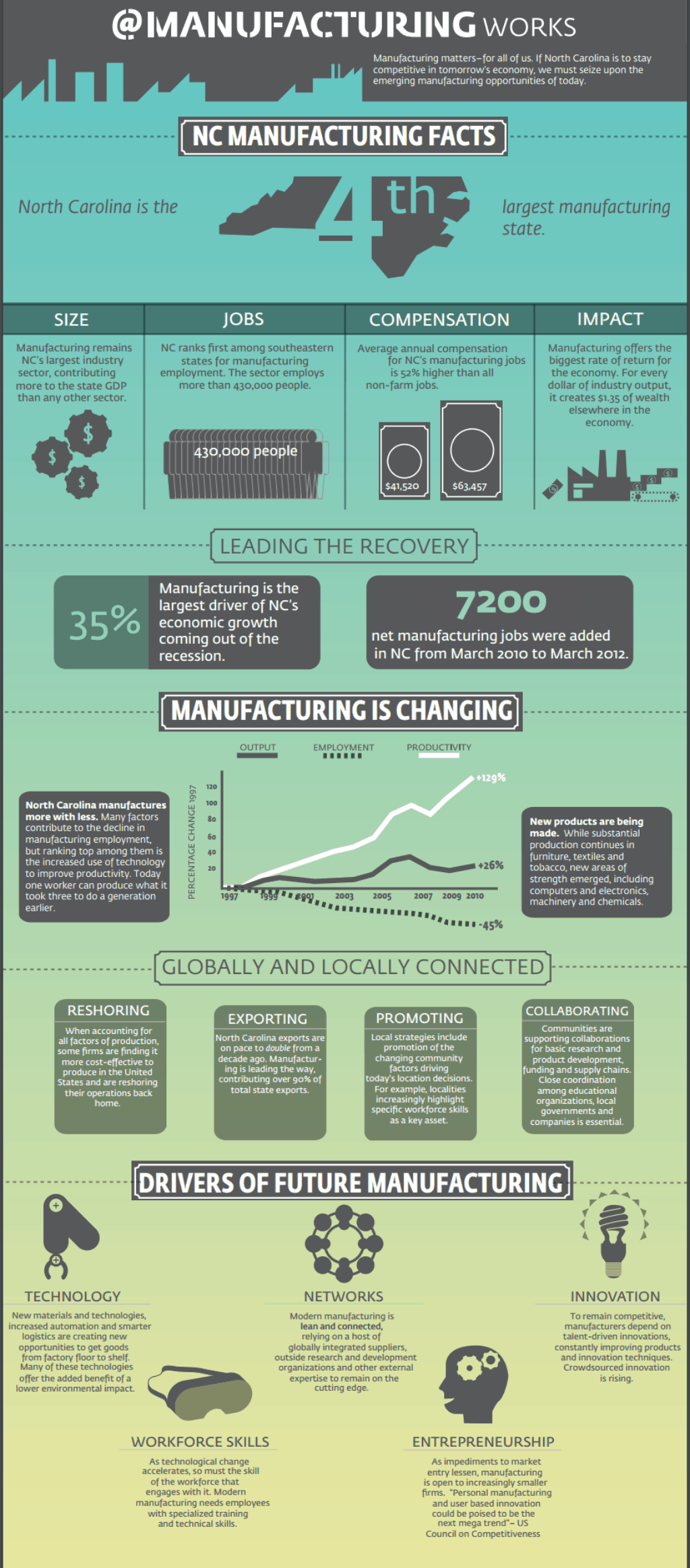

The Institute for Emerging Issues held an emerging issues forum on @Manufacturing Works, looking at the future of manufacturing across our state. Here is a map from TIME magazine on manufacturing growth nationally and then an infographic developed by IEI for the forum. What could a “Made in North Carolina” economic development strategy mean for our rural counties?

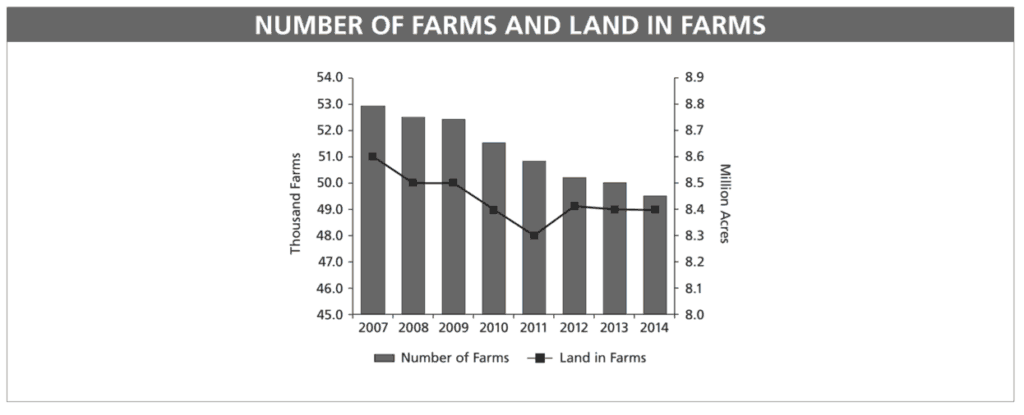

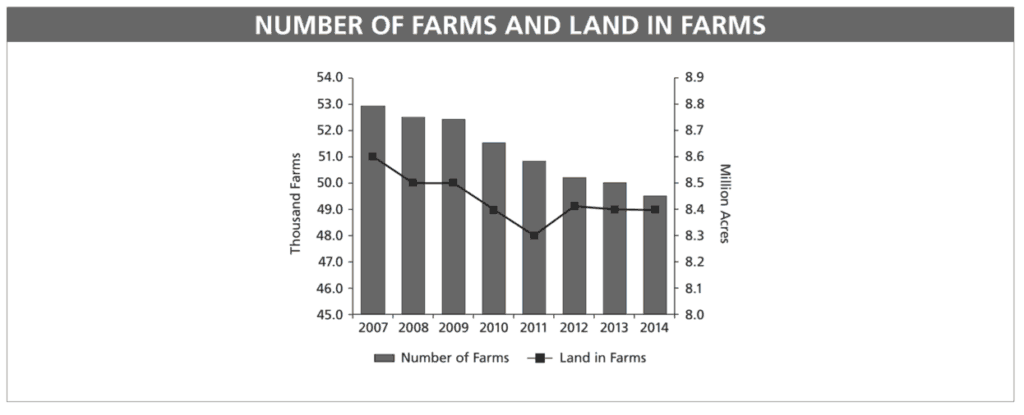

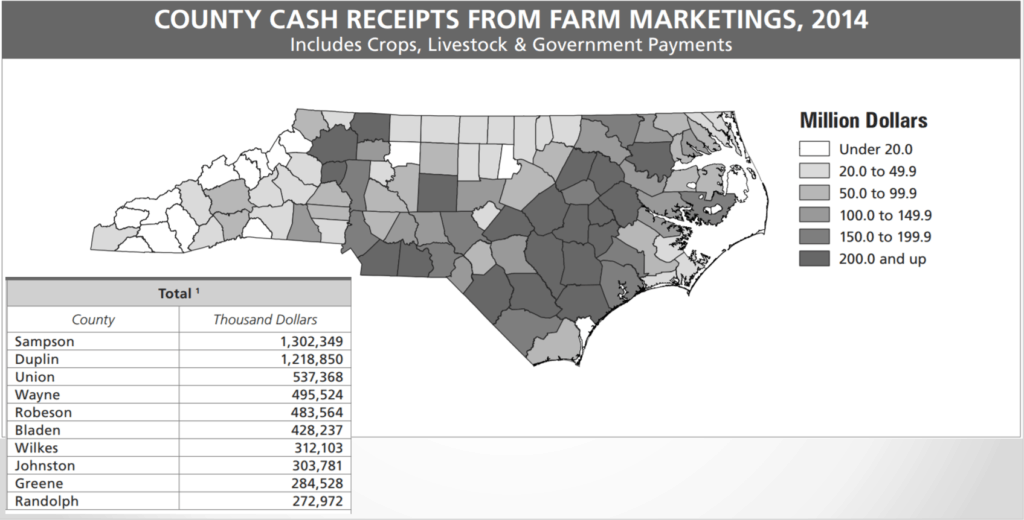

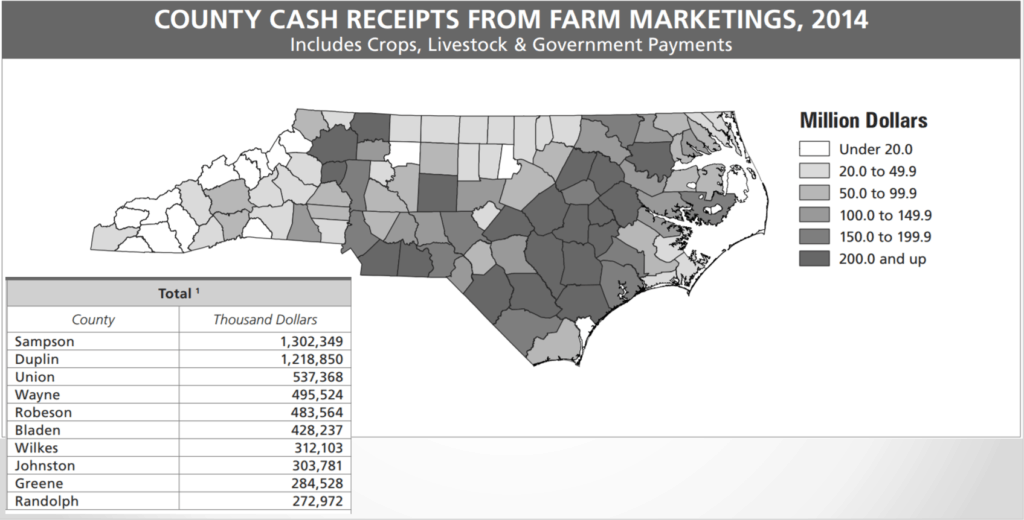

Agriculture is still big business in North Carolina, with our state leading the nation in production of tobacco and sweet potatoes, and second in the nation in poultry and hogs. However, the number of farms and land in farms is declining. This trend may have a disproportionate impact on southeastern North Carolina.

Small family farms have bound communities in rural areas together and driven local economies over time.

Guillory says, “The end of the federal tobacco program resulted in a consolidation in Eastern North Carolina — fewer farms, more acreage. Yes, still family-run in many case, but younger more technologically savvy, and equipment-ready, farmers bought up land — and they grow tobacco under contract to cigarette companies and exporters. Tobacco is no longer the hot political issue that it used to be.

Hog and poultry represent major segments of the agriculture sector. There’s still a cap on hog production but it remains huge. Farmers produce hogs and chickens under contract to big meat producers. Despite efforts to move farmers to alternative methods of disposing of animal waste, the state still faces environmental issues with the presence of lagoons (the polite word for cesspools) across the coastal plain, vulnerable to flooding.

In a more urban-suburban state, production of shrubs, ornamental plants and Christmas trees have become major agricultural products.”

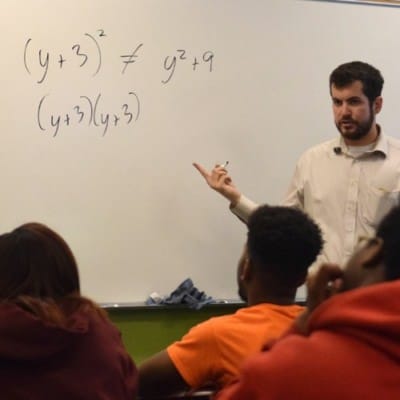

Education

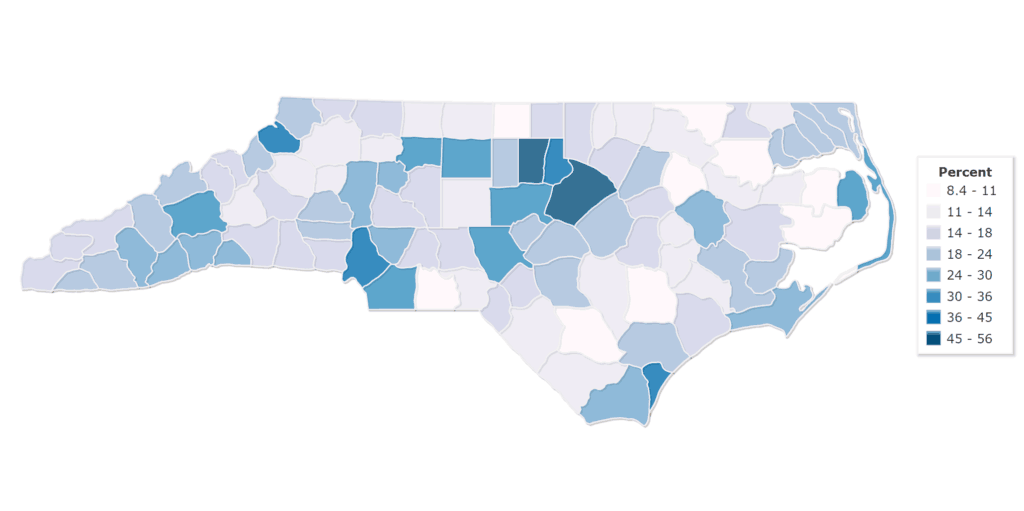

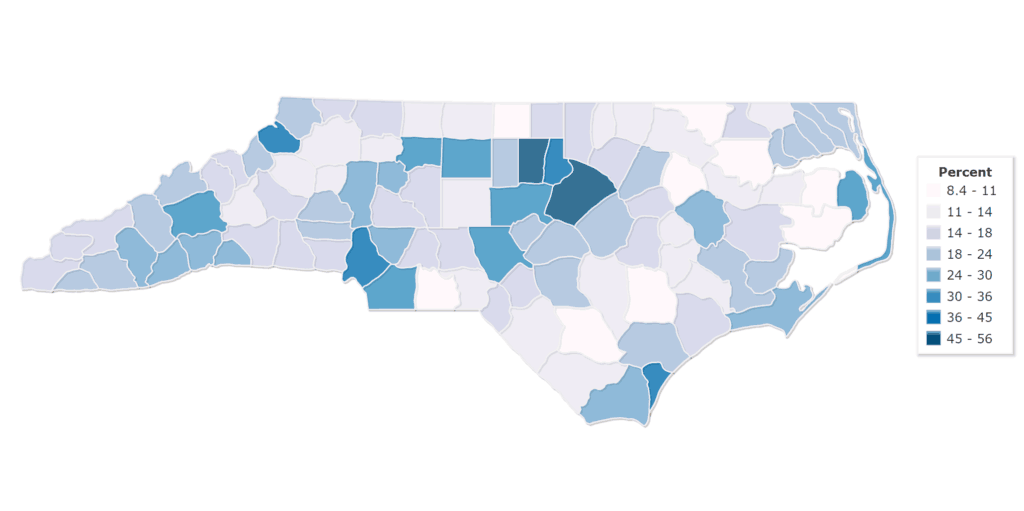

This map shows percent of people age 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree in North Carolina by county between 2009-13.

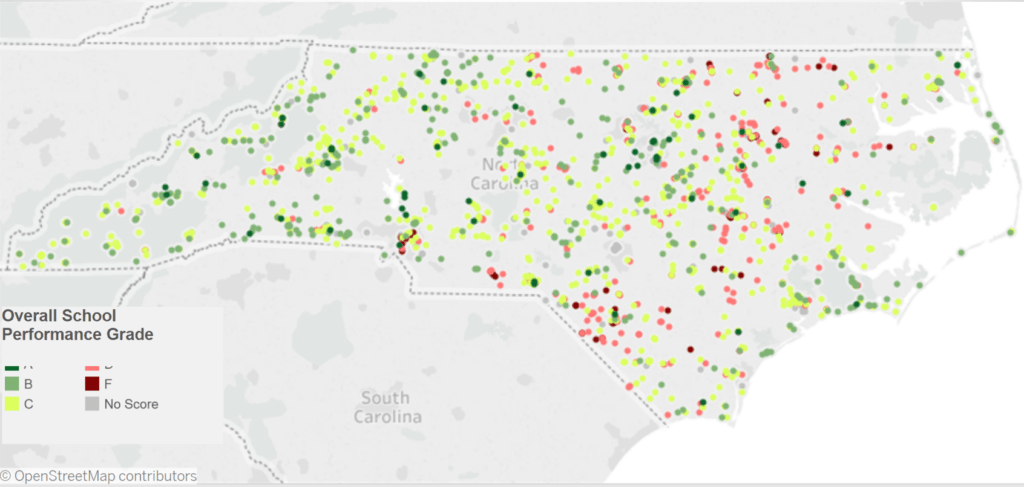

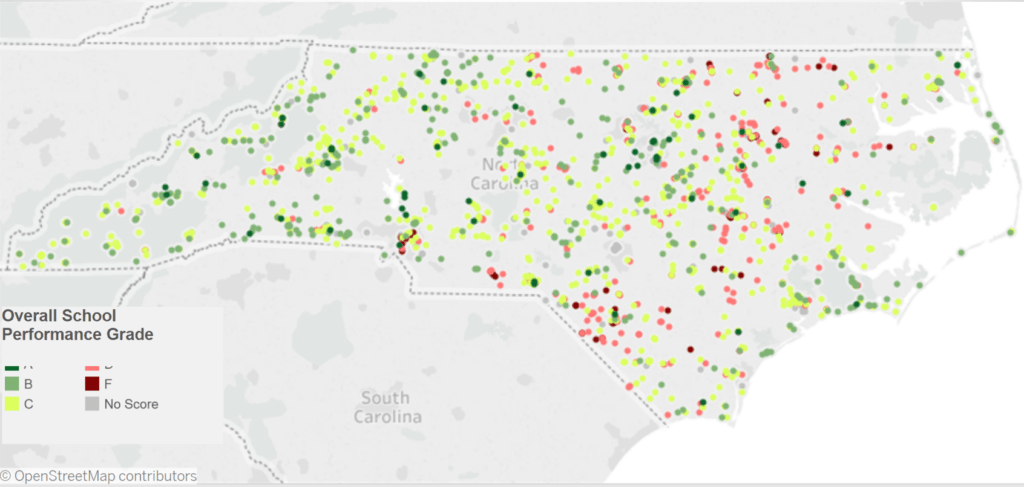

These are the A-F school grades for schools in the 80 rural counties. The coral color is a D, and the darker red is an F. Note the swath of D and F schools mirrors our stroke belt.

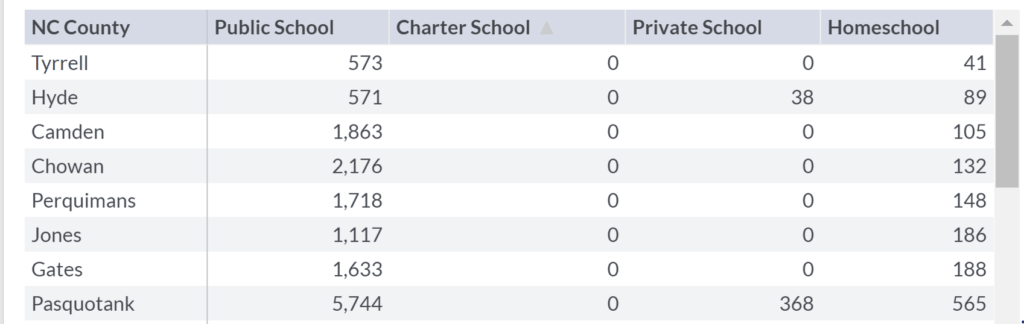

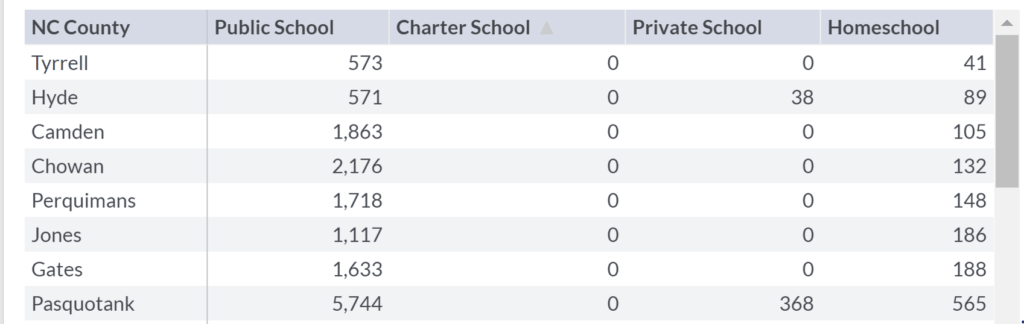

Smaller, rural counties tend to have less school choice.

A recent article in Education Week, entitled How Education Is Failing Rural America, says:

When young people in rural places finish high school, their options are often simple: stay and work in whatever industry or business is locally available, or leave to pursue higher education or other types of work. For generations, when manufacturing supported entire communities, logging and fishing industries boomed, and family farming dominated the landscape, young people had multiple opportunities to stay in their thriving rural communities. Students who were able to go to college might return, if they chose, to open small businesses or work in upper management. However, as the economic vitality of these communities has slowly—or in some cases, quite abruptly—declined, the opportunities for educated young people to return to their communities has also declined.

The result is that instead of providing a pathway for youths to go out of their communities and potentially return with a knowledge base of new experiences, rural public schools have simply become engines of exodus, educating students for labor markets and communities located elsewhere. Educated young people, for the most part, leave rural places and, even if they want to, cannot return. The phenomenon is so common that it has a name: rural brain drain.

…

Many researchers in rural education argue that rural schools themselves can be drivers of economic development. Entrepreneurial thinking by educational leaders at the state, school, and district levels can lead to greater opportunities for schools and communities to collaborate on attracting families, retooling local economies, and providing needed skills development to community members.

Health

These are overall health outcomes by county across North Carolina. The darker green counties are those with the worst overall health outcomes.

Aging

Source: EdNC, based on data from OSBM

By 2036, in 37 counties across North Carolina, 25 percent or more of the population will be 65 years of age or older. In nine counties, 30 percent or more will be 65+ (from highest to lowest, Polk, Transylvania, Brunswick, Chatham, Pamlico, Clay, Cherokee, Henderson, and Perquimans).

Politics

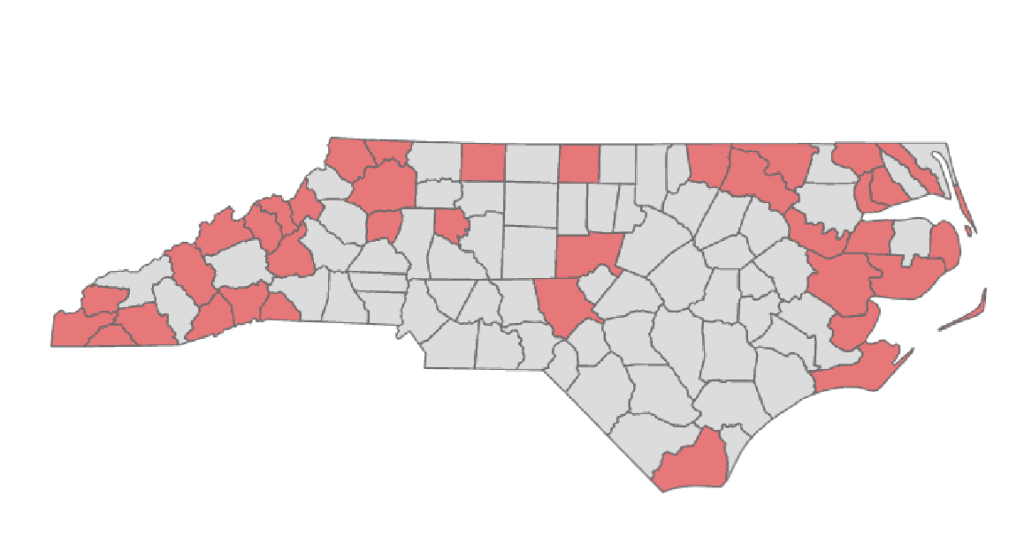

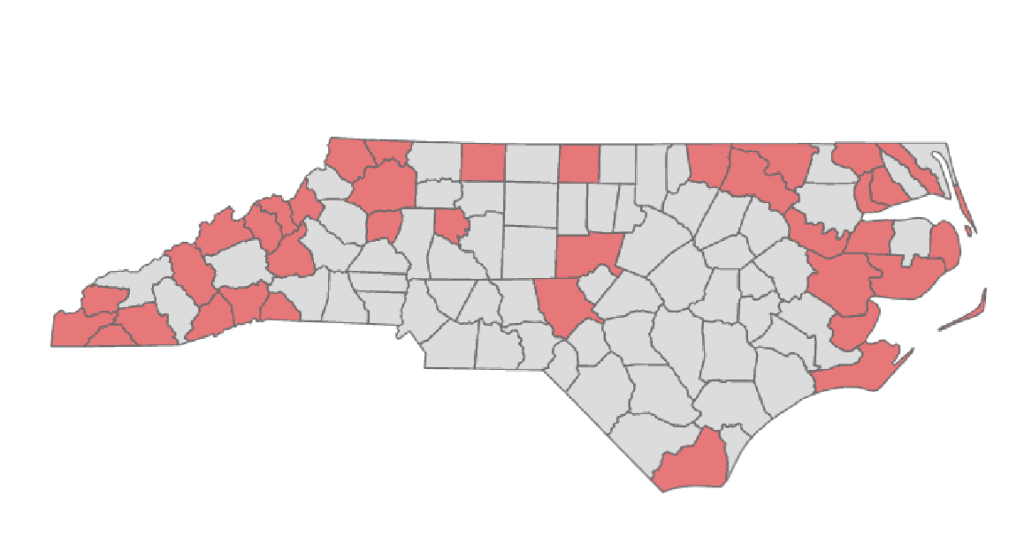

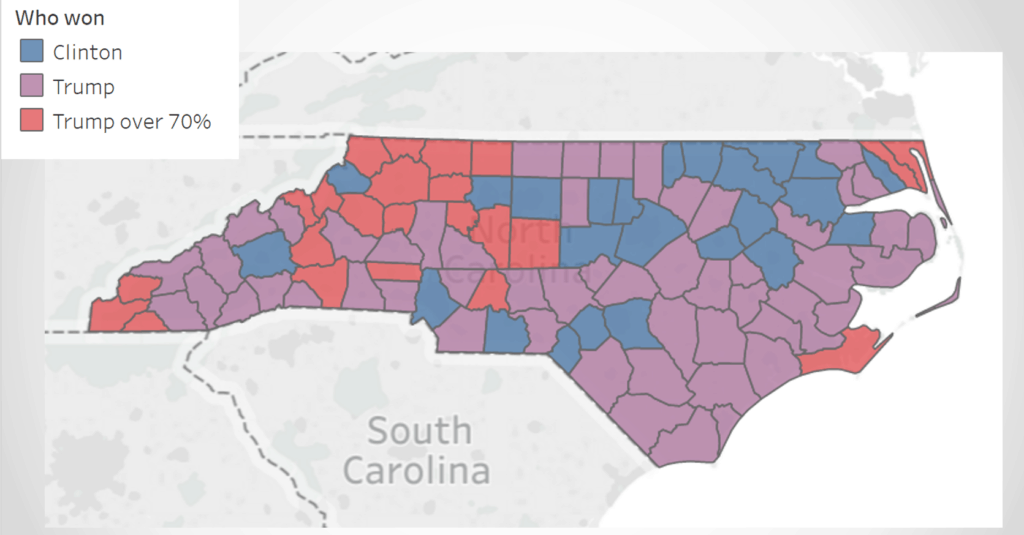

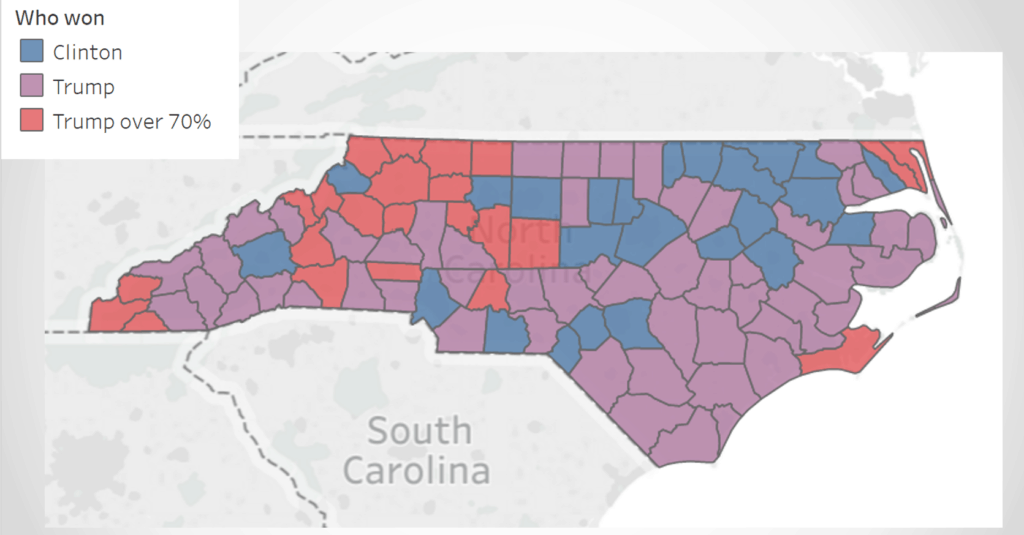

We created this map of the general election presidential results in 2016. Donald Trump won 76 of our 100 counties. He won 23 of our counties with more than 70 percent of the vote, and in this map, these counties are red. He won 53 more counties with closer margins, and in this map, these counties are purple. Hillary Clinton won 24 counties, following our crescent from Raleigh to Charlotte, and in this map, these counties are blue.

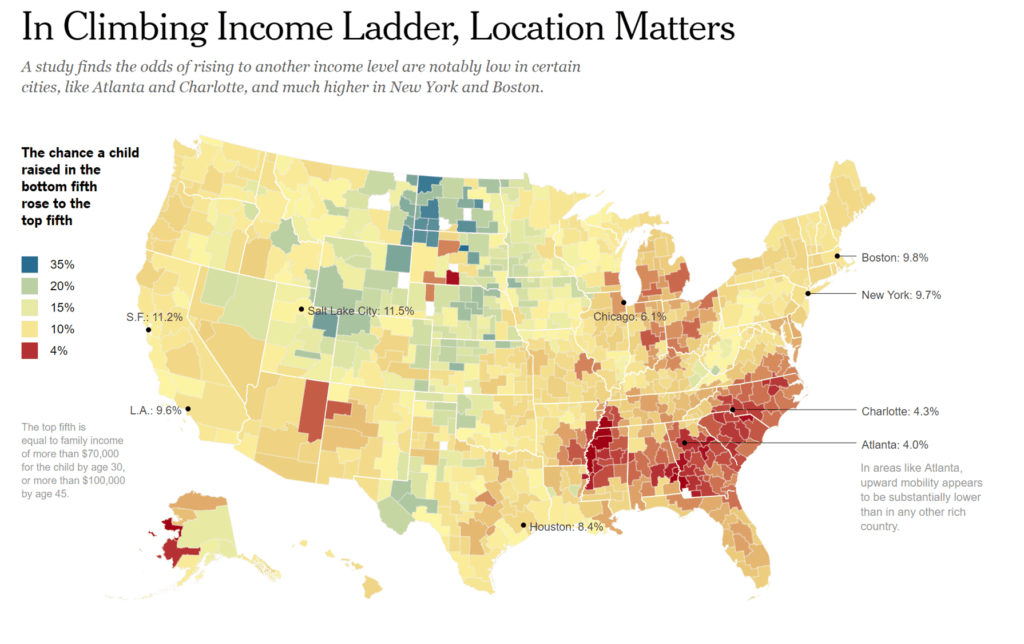

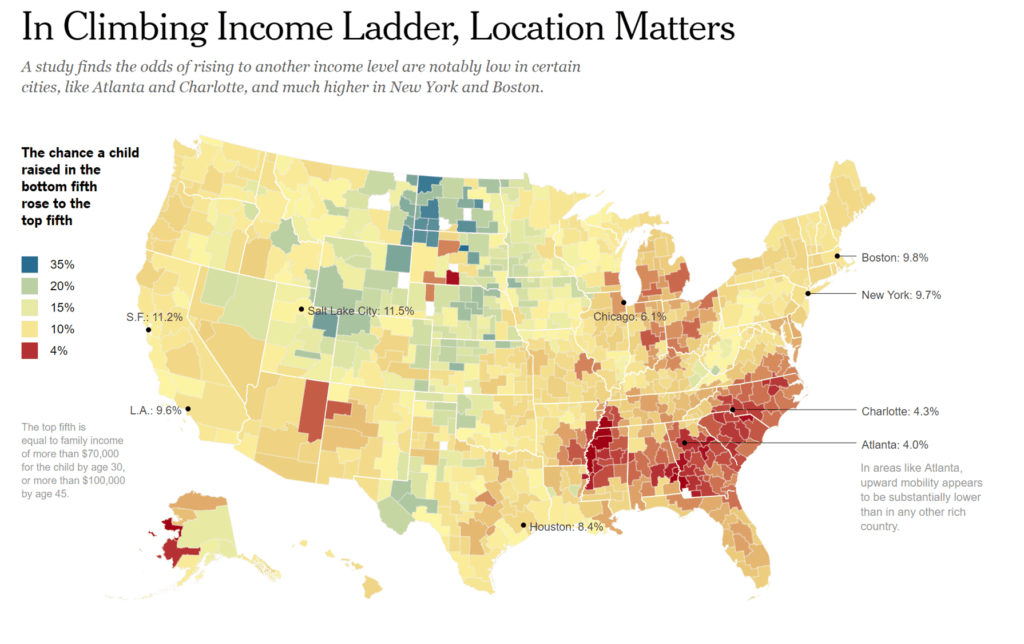

This map by the New York Times assesses the impact of location on upward mobility.

Why does it matter?

Too often the differences in our counties are ignored or treated as one grand distinction between urban and rural.

“This is a bigger issue than a rural/urban divide. The issue is an argument for bringing people together…this is as much culture as it is economics. We need to drill down into the cultural disconnect to find solutions. It is tearing America apart.” Secretary Glickman

When we look at these maps we see clusters of counties that are going to face persistent challenges for decades to come. Senator Bill Purcell (D-Scotland) once said to me, “There is no smell like the smell of a dying community.”

Is our state strategy to help them manage decline?

Or is it to saturate them with possibility?

When I showed these maps to Joe Stewart over at the N.C. Free Enterprise Foundation, he told me about his theory of creating a “Mayberry effect” across our state:

“For rural parts of North Carolina that continue to face population decline, the economic model going forward is probably less about attracting traditional large-scale employers and more leveraging relative proximity to a big city while providing small town charm some gig economy workers seek.

Features like broad band access and high quality schools can draw families whose breadwinners can make their living anywhere they can access a computer keyboard. Rural communities can be the Mayberry some in this segment of the workforce seek — but with a brew pub instead of a diner, and friendly neighbors who are from Mumbai not Pilot Mountain.”

Leverage points for politics, policy, and philanthropy

- Think about clusters of counties instead of regions

- Identify and invest in emerging rural leaders

- Invest in rural convenings, fostering collaboration to develop local solutions

- Invest in revisioning rural economics