The rise of educational technology over the past 20 years is not news to anyone. With companies such as Google now getting into the market of information and communications technology (ICT) in education, it is vitally important that we, as educators, identify effective and productive technology for use in STEM (and other) education applications.

No country has turned more heads in the world today than Singapore — topping the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores as the top educational system in the world for STEM education. 1 This summer, a team of Burroughs Wellcome Fund Scholars had the opportunity to observe just how Singaporean schools utilize ICT. While we were taken aback by the incredible technology implemented in Singaporean schools, we also had questions.

Who is it for?

Does student performance benefit from increased ICT usage and involvement?

Or is it the efficacy of teachers/other resources?

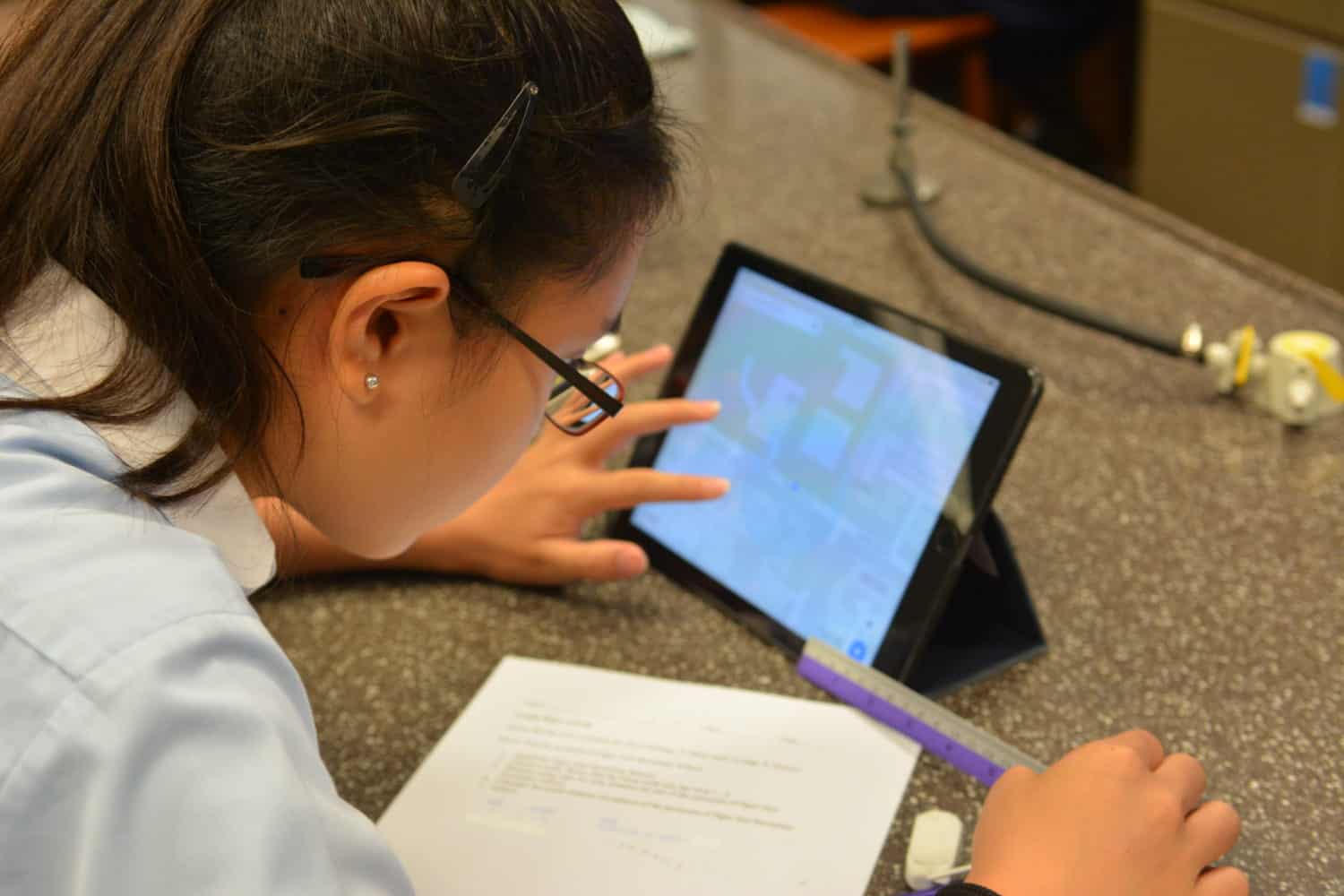

Adrian Lim, the director of Singapore’s Infocomm Development Authority (iDA), was more than willing to show the tremendous progress Singapore has made in educational innovation through their mass funding of ed tech in their school systems. Multiple schools that we toured reflected their innovation. Beyond Smartboards, students had wide usage of tablets, e-readers, and cloud software. These schools had developed Learning Management Systems that provided immediate feedback and data to drive further instruction in class and real time. Other innovations included uses of sensors for research-based and project-based learning tasks involving the Internet of Things (IoT). Adrian Lim was forthcoming that Singapore emphasized the value of innovation in education and achieved success through the government collaboration with these resources.

However, resources and technical education do not equal success. Singapore has had a mindset encouraging innovation and strong education systems since its foundation. The government has had a vested interest in providing technically and vocationally skilled workers. They accomplished this through the development of the Institute for Technical Education (ITE). However, this was just a start. As a small nation that saw the trend toward a knowledge-based economy, Singapore heavily funded research and industry, including its flagship universities NUS and Nanyang Technical University. With heavy investment, Singapore attracted quality human capital. Now, with some of the brightest minds in the industry, Singapore has begun funneling money into ICT research. Research heavily detailed in its “master plans” and development of organizations such as iDA.

The Singaporean government believes education provides massive public and private returns, and this investment has clearly paid off. In terms of attracting capital and returns on investment in education, most would think of higher education, but Singaporeans thought otherwise. By adapting a bottom-up approach, Singaporeans are investing more of their funds in primary and secondary education. By developing a strong foundation, Singapore can prepare a better labor force and quality future citizens.

With strong salary incentives, and multiple career paths for advancement, Singaporean schools recruit some of the best and brightest as primary and secondary teachers. Teaching is viewed as a highly valued profession, and applications for a teaching position are highly competitive. Consequently, teachers must go through intensive training at the National Institute of Education (NIE) to become teachers. The result of this intensive training is a teacher trained in the best educational practices and who is provided plenty of opportunities and time for professional development and growth. This is continued throughout the beginning of teaching through strong mentorship programs at the Academy of Singaporean Teachers (AST), and at least of 100 hours of professional development.

With all of this time, teachers are never required to come up with lessons or train themselves in the use of new curriculum and ICT resources. Before any new tech is implemented in primary and secondary schools, it is thoroughly tested at AST, iDA, and NIE. Lesson plans, projects, and practical uses for the technology are developed prior to implementation, which is offered in the multiple voluntary weeks off for teachers as professional development during the school year. With time off, benefits, and plenty of support, teachers are excited to use technology, not burdened by it.

To answer our final question, students have not fully benefited from the implementation of just ICT, but they have benefited from the strong priority that the Singaporean government has placed on the mindset of its education system. With funding, plenty of government support, high incentives for teacher recruitment, and best practices and high levels of human capital, Singapore has produced an environment for student success prior to the use of ICT. The U.S. K-12 school systems can benefit from this mindset, but if it truly wants to increase performance it would need to change its priorities. The motivation for Singaporean investment is clear — increasing production, human capital, and future resources — and the payoff has been enormous. With an investment in primary and secondary education, the U.S. and other international institutions have a hope for returns on their investment even without the use of ICT.