|

|

When you hear the word “relay,” you may think of races between children, passing along a message, or a variety of other things.

But to educators in the Public Schools of Robeson County (PSRC), this word carries a different meaning.

Relay – also called Leverage Leadership – is a professional development model designed to help principals better support teachers by delivering more manageable feedback. The model follows an approach to help teachers “get better faster.”

What is Leverage Leadership?

Leverage Leadership poses that principals should spend 85% of their day on instructional leadership. This includes time in classrooms, one-on-one coaching with teachers, data meetings, and more.

“It’s just about coaching so that you can keep on getting better. It’s really not about making anybody the expert in the room,” Windy Dorsey-Carr, assistant superintendent of curriculum, instruction, and accountability at PSRC, said.

When visiting classrooms, instructional leaders can provide real-time feedback that teachers can apply immediately.

Administrators are encouraged to provide “bite-sized” pieces of feedback. Dorsey-Carr said this means coaches are encouraged to only provide feedback that teachers can actually apply in the classroom within a week.

“It doesn’t matter where you are, we’re going to grow you, make you just a little bit better each week — not give you this laundry list of things to work on,” Dorsey-Carr said. “It’s thinking about just one little piece that you can take and help us teach or grow in a week.”

Following this method, Dorsey-Carr said teachers are less likely to become overwhelmed by the amount of feedback they receive.

This model is driven by a master calendar that principals make each week. It guarantees that they and their teams have time to visit teachers, and provide real-time instruction along with additional feedback throughout the week.

There are seven levers – led by instruction and culture – that guide the Leverage Leadership approach:

- Data-informed instruction: Define the roadmap for rigor and adapt teaching to meet students’ needs.

- Instructional planning: Plan backward to guarantee strong lessons.

- Observation and feedback: Coach teachers to improve learning.

- Professional development: Strengthen culture and instruction with hands-on training that sticks.

- Student culture: Create a strong culture where learning can thrive.

- Staff culture: Build and support the right team.

- Managing school leadership teams: Train instructional leaders to expand their impact across the school.

Dorsey-Carr said implementing the model district-wide is a slow process. While there are seven levers in the model, she believes the district should prioritize which are most important and slowly implement those before moving on to the next.

“You have to think about what’s the highest need first and start with that,” Dorsey-Carr said.

Leverage Leadership at work

Amanda Graham, St. Pauls Elementary School principal, has witnessed the benefits of Leverage Leadership in her school.

Graham started the 2021-22 school year as the school’s new principal. She spent the school year piloting the Leverage Leadership program with third grade teachers.

Graham said the success of the model relies on teacher buy-in.

“They know that I’ll do the work with them,” Graham said. “They have to know that, first and foremost, I’m a teacher too. And if you’ll let me, I will help you. If you let me, I will coach.”

There are three core ideas in Leverage Leadership:

- Maximizing time in schools

- Data-driven instruction systems

- Flexible support for turnaround

“It’s all about the students and the teachers and everyone growing,” Graham said.

In schools, these core ideas can take shape in various ways.

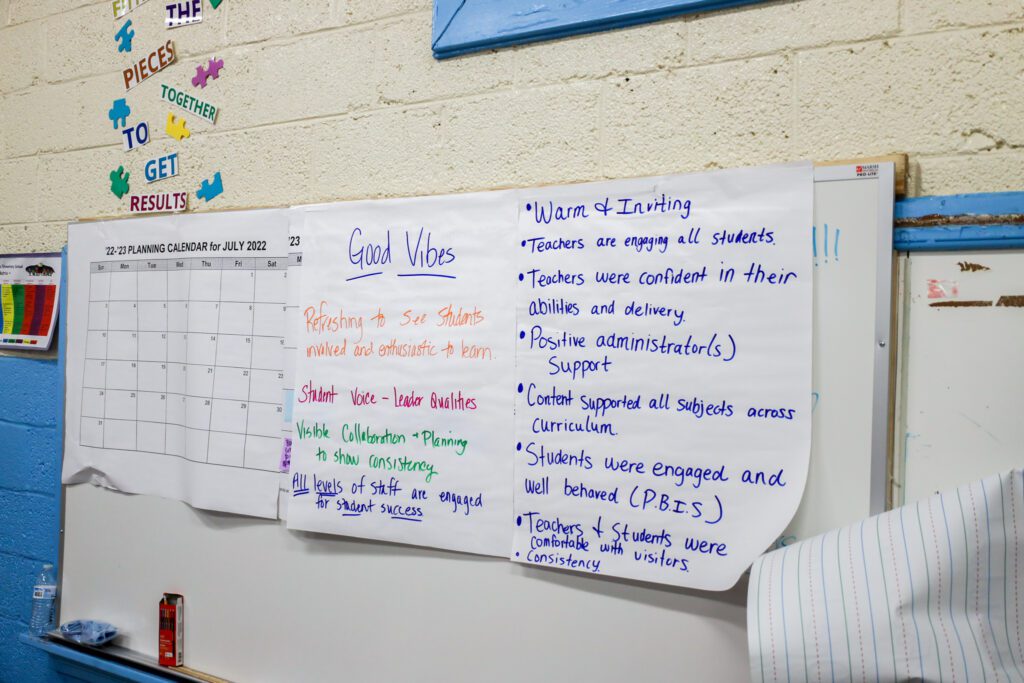

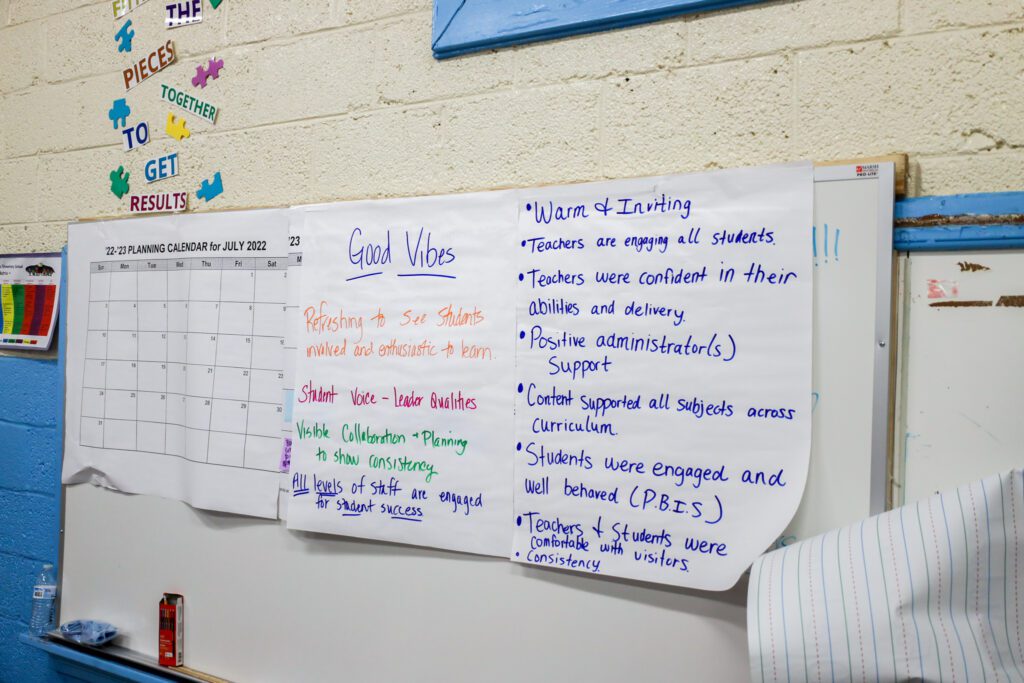

Each week, schools hold meetings with their instructional team – usually consisting of principals, assistant principals, and instructional coaches. They plan their week based on “trends” they see in classrooms across the building. Instructional leaders discuss school-wide “glows” and “grows.” Glows are areas where instruction is thriving, while grows are areas that could use improvement.

It’s in these meetings that instructional leaders determine what kind of feedback teachers need. Should they hold a grade-level data meeting? Should they host a practice clinic?

Instructional leaders – principals, coaches, and teachers alike – use their playbooks to effectively implement this approach. Creating an efficient calendar is one way to maximize time through Leverage Leadership. It ensures that even as principals handle discipline and managerial tasks, there is always time built into their calendars to get into classrooms and provide real-time feedback.

Data guides the feedback principals, coaches, and teachers provide. For each, the data helps lead instruction and determine how to best re-teach concepts that students may be struggling with, how to better differentiate instruction, and overall, improve best practices.

Brittney Norton teaches third grade at St. Pauls Elementary School. She said having more student data and more opportunities to meet with her principal have been beneficial.

“It’s bringing in more data to kind of look at and figure out what works best for certain students, and what groups I can put them with, and how to make my small groups more beneficial,” Norton said. “It helps with differentiation, for sure.”

Last year, St. Pauls Elementary School exceeded growth for the first time since 2016. After piloting the Leverage Leadership program with third grade teachers, Graham saw particularly promising growth in that grade.

Implementing district-wide

After piloting the program with 12 schools in the 2021-22 school year, PSRC is now implementing Leverage Leadership district-wide.

A major benefit of implementing the approach district-wide is that there’s a common language among administrators, principals, and teachers.

“There’s a common language now because everybody uses the same terms,” Dorsey-Carr said.

Dorsey-Carr said another advantage of this model is that it makes education in the district more equitable.

“What we were working on is how to provide that equity now,” Dorsey-Carr said. “Thinking about how do we redo our resources to really meet those needs, so that those opportunities are there.”

In some ways, the model hasn’t changed much – rather it’s improved systems and conversations in the district, and it makes the district more intentional.

“Meetings look very different. Discussions are very different – about students, about data, about lesson planning. I’ve seen teachers grow tremendously in their skill set,” Dorsey-Carr said.

Anthony Barton is the principal at the Public Schools of Robeson County Early College High School. Initially, he was unsure about implementing the model in his school. But seeing Leverage Leadership in action, Barton sees the model as a way to prevent a “grave” instructional mistake.

“When you walk around with the teacher and monitor together, and then you spar and say, ‘What did you see? What did I see?’” Barton said. “That’s the gap. Let’s fix it now.”

Barton said the model still relies on teachers’ strengths as content experts but pushes them to think of different instructional strategies to help them excel and grow.

This school year is the first where all schools in the district are participating in the Leverage Leadership model. Dorsey-Carr said implementation is slow but shows promising outcomes.

“It’s a good thing. We’re seeing a lot of growth in a lot of areas,” Dorsey-Carr said. “It’s going to take us a few more years.”

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the grade level that Brittany Norton teaches. It has been corrected.