Abstract

School choice is a popular and controversial topic across the nation. School choice options include both public schools such as charter schools and magnet schools, as well as private school options. In North Carolina, the cap was lifted on the number of charter schools in 2011 and since that time additional charter schools have opened each year. In Mecklenburg county there are two main school choice options: magnet schools that operate within the Charlotte Mecklenburg School district and charter schools that operate independently. This study compares and contrasts the magnet schools and charter schools in Mecklenburg County in the areas of academic outcomes, funding and expenditures, staffing, and opportunities for students. Findings form this study indicated there are differences in academic outcomes between magnet schools and charter schools; magnet school students have higher grade level proficiency rates and higher graduation rates. In addition, findings indicated that charter schools and magnet schools are given equal per pupil funding, but there are differences in expenditures. Charter schools are also associated with hidden costs for families and request for parent and community donations. Findings indicated charter schools had less licensed teachers than magnet schools and higher student teacher ratios with a greater number of administrators. Finally, magnet schools all had specific academic programs, while most charter schools described a more general academic program.

Introduction

Public school choice, including the charter school option, has become a popular and controversial topic across the nation. Supporters of school choice claim that bringing market-based competition to the school system will force all public schools to improve in order attract and retain students (Chubb & Moe, 1990; Hoxby, 2003). However, results of school choice programs have not been consistent with these claims. School choice has been associated with increased racial segregation (Saporito, 2003; Rossell, 2002; Bifulco, Ladd, & Ross, 2009; Renzulli & Evans, 2005) and inconsistent student outcomes (Zimmer, et al., 2009).

Giving families greater choice with respect to educational opportunities for their children was one of the purposes of the general statute that authorizes charter schools in North Carolina. It is also evident within the statute that one purpose of having charter schools in the state is to provide options that will better serve students by allowing for greater innovation. According to North Carolina General Statute § 115C-218.a:

The purpose of this Part is to authorize a system of charter schools to provide opportunities for teachers, parents, pupils, and community members to establish and maintain schools that operate independently of existing schools, as a method to accomplish all of the following: (1) Improve student learning; (2) Increase learning opportunities for all students, with special emphasis on expanded learning experiences for students who are identified as at risk of academic failure or academically gifted; (3) Encourage the use of different and innovative teaching methods; (4) Create new professional opportunities for teachers, including the opportunities to be responsible for the learning program at the school site; (5) Provide parents and students with expanded choices in the types of educational opportunities that are available within the public school system; and (6) Hold the schools established under this Part accountable for meeting measurable student achievement results, and provide the schools with a method to change from rule-based to performance-based accountability systems. (North Carolina General Assembly, n.d., § 115C-218.a)

The reality in North Carolina is that charter schools do not often meet the purpose as stated above. In a study entitled The Impacts of Charter Schools on Student Achievement: Evidence from North Carolina done by the Terry Sanford Institute for Public Policy at Duke University, researchers found that “students make considerably smaller achievement gains in charter schools than they would have in traditional public schools” (Bifulco & Ladd, 2006, p.50). Despite this evidence, charter school applications continue to get approved by the state, charter schools continue to open and families continue to enroll students in them thinking they are making a positive educational decision. In addition, children who return to the district from charter schools often have some academic gaps. Based on nationwide studies, almost two-fifths of charter schools (37% of them) show learning results that are significantly worse than their traditional public school counterparts (Miron & Applegate, 2009).

In this study, the researcher compares and contrasts two types of school choice options within Mecklenburg County in North Carolina. The county includes 25 charter school options (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, n.d.-e) and is a large urban district that offers 45 magnet school options (Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools, 2015). The magnet schools in the county operate within the Charlotte Mecklenburg School (CMS) district and follow the laws and policies of traditional K-12 schools in North Carolina. The charter schools operate independently of the local school district and follow a different set of laws and policies established for charter schools in North Carolina. Although there are many differences between charters and magnets, both types of schools are funded by the state and both participate in the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) accountability program. Since these two factors are the same for both types of schools, it sets the stage for a comparison and contrast between magnet and charter schools with regard to return on investment. Specifically, in this study the researcher examined the similarities and differences between the two types of schools in four areas: student academic outcomes, funding and expenditures, staffing, and program offerings and opportunities. Qualitative document analysis was conducted to compare and contrast charter schools to magnet schools in the areas of funding and expenditures, staffing, and program offerings and opportunities. Staffing and expenditures were also compared quantitatively using data obtained from NCDPI. A quantitative comparison of North Carolina End of Grade and End of Course tests along with graduation rates was used to determine similarities and differences in student academic outcomes between the two types of schools.

Background of Study

School Choice. The term “school choice” has a long and inconsistent history in the United States. The term is first associated with a movement in the 1920s to Americanize immigrants and the subsequent court decisions that gave parents the ability to choose private schools as a means to satisfy compulsory education requirements (Minow, 2011). School choice became popular again in the 1960s with “freedom of choice” plans used by southern states to avoid desegregation by allowing black and white students the freedom to remain in their segregated schools (Forman, 2005; Minow, 2011). Soon after, in the early 1970s, school choice in the form of magnet schools became a popular solution proposed for the desegregation of schools. As a result, magnet schools were put into place in many urban school districts. Proponents claimed that magnet schools would attract white students to high minority schools since they offered specialized programs, curricula, and approaches (Minow, 2011; Davis, 2014). Most recently, school choice has been associated with two additional options. The first is voucher programs that allow students to receive public funding to attend private schools. The second is the public charter school movement that is continuing to proliferate across the nation (Minow, 2011). This study focuses on the following two forms of school choice: magnet schools and charter schools.

Magnet Schools. Magnet schools began in the 1960s in response to legal decisions to desegregate public schools. They were first designed to attract students and increase voluntary desegregation of schools (Blazer & Miami-Dade County Public Schools, 2010). They have grown and evolved over time to serve additional purposes. “These programs are being implemented in an increasing number of school systems purportedly to improve academic standards, promote diversity in race and income, and provide a broad range of offerings to satisfy individual talents and interests” (Hausman & Brown, 2002, p. 257). Magnet schools offer specialized programs that focus on a theme or an approach. These include theme options such as Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM), International Baccalaureate (IB), Fine and Performing Arts or Language Immersion. Other magnet schools may focus on a particular approach, such as Montessori (Magnet Schools of America, n.d.).

Charter Schools. Charter Schools began as a school choice option in Minnesota in 1991 when the first charter school law was passed by the Minnesota legislature with the purpose of increasing innovation and opportunities (National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, n.d.). The first charter school opened in 1992 and since that time charter schools have become a popular form of educational reform and school choice across the nation (National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, n.d.). By the 2013-2014 school year, there were 6,440 charter schools in operation serving 2.5 million students (National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, n.d.). Although the specific laws and regulations that govern charter schools are different in each of the 42 states that have them, there are some things that are common to all charter schools. Like traditional public schools, they are publicly funded. Unlike traditional public schools, they are given freedom from some policies and regulations. Charter schools operate based on an agreement with the state, board, or agency that grants the “charter.” They are held accountable for meeting the terms of that agreement along with any additional accountability measures the state, board or agency may require (Zimmer, et al., 2009).

Problem Statement

North Carolina is among the 42 states in the United States that have public school choice options that include charter schools (National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, n.d.). In 2011, North Carolina lifted the cap limiting the number of charter schools in the state and there is currently no cap on the number of charter schools. Prior to the cap being lifted, the number was limited to 100 charter schools in the state (North Carolina General CHARTER VS. MAGNET 6 Assembly, n.d.). Since that time, the number of charter schools in Mecklenburg County has increased each year. Based on the number of charter applications that have been submitted for upcoming years, the trend suggests this increase will continue (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, n.d.-e). As the number of charter schools increases, the number of students attending them increases also, impacting funding and resource allocation for traditional public schools and districts. According to North Carolina General Statute § 115C-218 Article 14a, the first stated purpose of the establishment of charter schools in North Carolina is to “improve student learning” (North Carolina General Assembly, n.d., § 115C-218.a.1) However, based on the North Carolina School Report Card grades, charter schools are failing at a higher rate than traditional public schools. More than 13% (17 of 126) of the charter schools in North Carolina received a school report card grade of F, while only about 5% (129 of 2,439) of traditional public schools received that same grade (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-j).

Professional Significance

The researcher intends for the results of the comparison and contrast between charter schools and magnet schools to be used to identify what is working well and inform CMS district efforts and funding decisions. The significance of this study lies in the continued growth in the number of charter schools in Mecklenburg County and North Carolina. One of NCDPI’s goals is to ensure that “Every student in the North Carolina public school system graduates from high school prepared for work, further education and citizenship” (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, n.d.-a, Goals section). To reach this goal, funding and resources need to be largely directed to support the types of schools and programs that are successfully moving students toward the desired outcomes. Improved understanding of the specifics of these innovative schools and how they impact students, will enable further work in Mecklenburg County with school choice options to more effectively educate and prepare students. The goal of this study was to compare and contrast the charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County. The two types of schools were compared and contrasted with regard to academic outcomes, funding and expenditures, staffing, and the program offerings and opportunities provided for students. The following research questions were investigated:

- Are there differences in student academic outcomes, as reported by proficiency on state exams and graduation rates, between charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County? If so, what are the differences?

- Are there differences in funding and expenditures between charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County? If so, what are the differences?

- Are there differences in staffing between charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County? If so, what are the differences?

- Are there differences in programs and opportunities provided for students in charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County? If so, what are the differences?

Methodology

Theory of Action

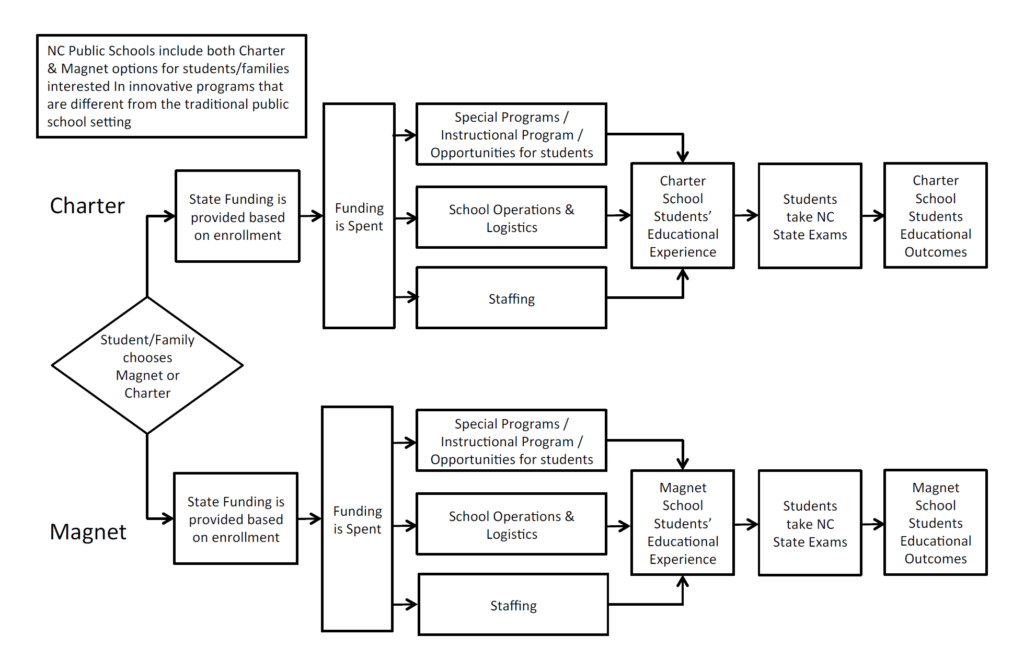

Figure 3.1 shows the theory of action for the progression from school choice to educational outcomes for students. The figure includes and connects the four areas that are the focus of this study: academic outcomes, funding and expenditures, staffing, and programs and opportunities provided for students.

Figure 3.1 Magnet and charter schools: Return on investment comparison

Theory of Action Narrative. School choice is a current, popular, and controversial topic with history in the United States going back to the 1920s (Forman, 2005; Minow, 2011; Davis, 2014). North Carolina supports school choice by enabling parents and families to choose between a number of public and private school options within the state (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, n.d.-f). Two of these options, charter schools and magnet schools, are advertised nationally as being innovative by offering specific curriculum or specialized approaches (Magnet Schools of America, n.d.; National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, n.d.).

When a student enrolls in a charter school or a magnet school, public funding is provided for that student to the school based on the monthly calculation of Average Daily Membership (ADM) (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). Ultimately, the amount of funding a school receives is based on ADM. ADM is the number of students enrolled in the school and taking classes for at least half of the school day. ADM values are calculated monthly by dividing the number of days in membership for all students in the school by the number of days in the month (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a).

Once the funding is provided to the school, it is spent in accordance with the laws, policies, and procedures required by the state of North Carolina. Magnet schools operate within the local school district and state funding is provided in the categories of position allotments, dollar allotments, and categorical allotments. The School Finance page on the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) website includes the laws and policies that govern how each of these allotments can be used and requirements for schools and districts. Position allotments are given by the state to the district for state licensed educator positions including teachers, instructional support staff, and administrators (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). When the district hires the certified educators for the position, they pay them based on the state salary schedule. The state covers the dollar amount, based on the state salary schedule, for the number of positions that the district is given (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). The district is not limited to a certain dollar amount; they are only limited to the specific number of positions they were given for certified educators. Dollar allotments are given by the state to the school district for things such as classroom materials, textbooks, teacher assistants and central office administrators (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). The school system is limited in these areas to the dollar amount that is allocated by the state. Categorical allotments are used for things such as transportation and non-instructional support personnel (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). The school system has some flexibility in how these funds are used, but is limited to the amount that is allocated (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a).

Charter schools in North Carolina operate independently of the local school district and follow separate laws, policies, and requirements. According to North Carolina Article 14A § 115C-218.10, “Except as provided in this Article and pursuant to the provisions of its charter, a charter school is exempt from statutes and rules applicable to a local board of education or local school administrative unit” (North Carolina General Assembly, n.d., § 115C-218.10). Charter school funds are allocated to the school as a dollar allotment with more flexibility on how the funds can be used (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). Charter schools are not required to pay staff according to the state salary schedule and not all teachers in charter schools are required to be licensed (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). Charters do not have to participate in the state employees retirement system or medical plan (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). In addition, they are not required to purchase on state contract or participate in e-procurement (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-f; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2014-a). Charter schools are not held to class size minimums or calendar laws and they are not required to provide transportation or lunch for their students (North Carolina General Assembly, n.d.). The Financial Guide for Charter Schools, which can be found on the Financial and Business Services page of the NCDPI website, details the laws, policies, and requirements that govern charter school finance. (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, 2015-d). The qualitative method of document analysis was used to compare and contrast funding, expenditures, and staffing between charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County.

A student’s educational experience in a school depends on the curriculum, programs, and opportunities that are offered, how the school is organized and managed, and the staff members that they interact with on a daily basis. All of these things together impact the education that the student receives and ultimately how they perform academically. Specific curriculum and specialized approaches play a role in student learning. When students are interested in what they are learning, they are more engaged in the classroom and learn more as a result (Ely, Ainley & Pearce, 2013). Teacher quality has been linked to student achievement in a number of studies. Stronge, Ward and Grant (2011) investigated the differences between highly effective and less effective teachers, as measured by student achievement. They found significant differences in student achievement between highly effective and less effective teachers. “The differences in student achievement in mathematics and reading for effective teachers and less effective teachers were more than 30 percentile points” (p. 348). In 2012, Metzler and Woessmann found that teacher subject knowledge had a significant effect on student achievement. Interesting curriculum and highly effective teachers are not the only things that impact the success of students. Involvement in extracurricular activities has been linked to higher academic performance (Knifsend & Graham, 2012) and lower dropout rates (Mahoney, 2014). Participation in high school sports has even been linked to a lower occurrence of childhood conduct disorder and adult antisocial behavior (Samek, et al., 2015). Involvement in leadership activities in high school has been positively linked to the attainment of education after high school (Rouse, 2012). Qualitative analysis includes comparison and contrast between charter schools and magnet schools with respect to school logistics, staffing, and the curricular, academic, and extracurricular opportunities they provide for students.

In North Carolina, student academic performance is measured using the North Carolina End of Grade (EOG) and End of Course (EOC) tests (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, n.d.-d). The quantitative analysis used both graduation rates and proficiency on North Carolina EOG and EOC exams to compare and contrast the academic outcomes of students in magnet schools versus charter schools.

Methodology

Description of the Sample. This study is a mixed methods comparison and contrast between charter schools and magnet schools within Mecklenburg County to gain insight into the return on investment with both types of schools. All charter schools and full magnet schools in Mecklenburg County that have been open for three or more full school years are included in the study. Charter and magnet schools that have not been open for three or more full school years have limited data, so they were not included. Based on information found on the Office of Charter Schools section of North Carolina Department of Public Instruction website, there are 25 charter schools that are currently operating within Mecklenburg County. Of the 25 operating charter schools, more than half (13 schools) are within the first three years of existence. Four are currently in their first year of existence and were not included in the study as a result. Six opened in July of 2014, and three charter schools opened in July of 2013, having only one and two school years of data available. There are 12 charter schools in Mecklenburg County that fit the criteria of being open for three or more years; these schools are included in the study. Ten of the 12 serve elementary students, another ten of the 12 serve middle school students and seven of the 12 serve high school students.

Based on information from the Magnet Programs section of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) website, CMS has 45 different magnet school options currently operating within the district (Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools, 2015). Similar to the group of charter schools, some of these schools have been open for only one or two full school years, limiting the data available. In addition, only 19 of the 45 magnet schools are full magnet schools with all students in the school participating in the magnet program. The other schools are considered partial magnet programs in which only a fraction of the students enrolled in the school are participating in the magnet program. For the purposes of this study, only the full magnet schools were included for the comparison and contrast with charter schools since the charter schools do not have any partial charter programs. Of the 19 full magnet schools within CMS, 17 have been open for three or more years. The 17 full magnet schools that have been open for three or more years fit the criteria and are included in the study. Thirteen of the 17 serve elementary students, 11 of the 17 serve middle school students and three of the 17 serve high school students.

Identification of Subjects. Charter schools and magnet schools were identified for participation in the study based on the school’s location in Mecklenburg County, the school’s operation for three years or more and the school’s operation as a full magnet or full charter school. All charter schools and magnet schools that fit the criteria outlined above are included in the study. Charter schools and magnet schools that do not fit the criteria are not included in the study due to insufficient data.

Assurances of anonymity and protection of human subjects. All data used for both the quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis within this study are publicly available data collected from North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools website and individual magnet and charter school websites. Quantitative data for EOC and EOG proficiency and graduation rates are disaggregated by demographic group with no individual student data or student identifiers.

Conclusion

Summary of Findings

There are differences in student academic outcomes between the charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County and the differences have become more pronounced since the 2012-2013 school year. The magnet schools in this study had better academic outcomes overall, as measured by grade level proficiency on North Carolina EOG and EOC tests and graduation rate. In addition, magnet schools in this study consistently had better academic outcomes for black students, white students, males, and economically disadvantaged students. Charter schools in this study consistently had better outcomes for Asian students. The academic outcomes for students with disabilities and Hispanic students were inconsistent for both magnet schools and charter schools.

There are differences in funding and expenditures between magnet schools and charter schools. Efforts were made by the state, within the law that authorizes charter schools, to ensure that charter schools are funded at the same per-pupil rate as other public schools, such as magnet schools. However, charter schools do have greater autonomy with spending. Charter schools consistently spent a larger percent of their budget on services and a smaller percentage of their budget on salaries and benefits as compared to the CMS district. Charter schools consistently asked for donations from parents and the community, sometimes with persuasive or potentially misleading language and with benefits to large donors. In addition, charter schools have more hidden costs for families than magnet schools. The majority of the charter schools in this study do not provide bus transportation or a free and reduced price lunch program. Also, uniforms are required by some charter schools and by some magnet schools, but the cost varies.

There are differences in staffing between magnet schools and charter schools in Mecklenburg County. Charter schools are required to have only 50% of their teachers be licensed. This has resulted in charter schools having a significantly smaller number of licensed teachers when compared to magnet schools. In addition, staffing data collected from charter and magnet school websites suggest that charter schools may have a higher student to teacher ratio and lower teacher to administrator ratio. There is some evidence in the data collected from websites that suggests some charter schools may have a higher teacher turnover rate than magnet schools of similar size.

Finally, there are differences in opportunities provided by charter schools and magnet schools in Mecklenburg County. The intention of the opportunity itself seems to be different based on magnet school documents as compared to charter school documents. Magnet schools seem to focus on opportunities for students and opportunities for improvement within the district. Charter schools seem to focus on the opportunity for students, teachers and the community to improve by separating from the district. Academic programs also differed between magnet schools and charter schools. All magnet schools offered specific academic programs (for example: STEM or language immersion); however, most of the charter schools offered more general academic programs. Both magnet schools and charter schools seemed to offer athletic programs at the secondary level. There was not enough information available on school websites to determine if there were differences in other extracurricular activities such as clubs.

Specific Meaning of the Combined Answers to the Research Questions

This study provides evidence to suggest that magnet schools have a greater return on investment than charter schools. The laws that authorize charter schools in the state of North Carolina ensure that charter schools receive per-pupil funding that is equal to that of the local school district where they are located. However, there is evidence to suggest that charter schools seek and receive donations from parents and the community and are more likely to have hidden costs for families, such as lunch or transportation. The same laws that provide equal funding also provide charter schools with a greater degree of autonomy in a variety of areas including their expenditures, staffing, and overall academic program. Although charter schools are funded at an equal per-pupil rate and given autonomy for the purpose of improving student learning, the academic outcomes of magnet schools are better than those of charter schools.

This difference in academic outcomes is potentially due to a couple of factors. First, there are differences in the staffing of charter schools as compared to magnet schools. Charter schools have a lower percentage of licensed teachers and this has decreased from 83.3% in 2013 to 71.5% in 2015. Over this same three-year period, the gap between charter school and magnet school proficiency rates went from no difference in grade level proficiency overall to a difference of about three percentage points overall, with magnet schools performing better. The gap in proficiency between magnet schools and charter schools has become even greater in specific subgroups: in 2015, black students in magnet schools had a proficiency rate that was 15.4 percentage points higher than the proficiency rate for black students in charter schools. The same was true for white students and economically disadvantaged students with proficiency rates that were 7.5 and 10.7 percentage points higher in magnet schools. As mentioned above, the difference in the staffing of the charter schools may be impacting the academic outcomes. Multiple researchers have studied the impact of teachers on student academic achievement. One study linked the overall professional competence of a teacher, defined as the pedagogical content knowledge, professional beliefs, work-related motivation, and self-regulation, to positive impacts on the quality of the instruction they provide (Kunter, et al., 2013). Similarly, Metzler & Woessmann (2012) found teacher subject knowledge does have a statistically significant impact on student achievement. Also, it is not only teacher quality that impacts student achievement; teacher turnover has also been linked to having a negative impact on student achievement (Ronfeldt, Loeb & Wyckoff, 2013).

The second potential factor is the lack of specific academic programs in charter schools as compared to magnet schools. Multiple studies have shown the positive impact of the specific magnet academic programs on student achievement (Gamoran, 1996; Betts, et al., 2006; Houston Independent School District, 2007). Although charter schools are part of “school choice,” many of them are lacking a focused or innovative academic program that would set them apart from traditional public schools. The difference in academic achievement may be related to this difference in academic programs.

Finally, there is some evidence to suggest that the spending practices of charter schools may impact the learning environment and overall academic performance of students. Overall, charter schools spent a smaller proportion of their budget on salaries and benefits than the traditional school district. It is possible that this difference in spending is due to the staff being less experienced or more simply due to employing less staff. Staffing information on school websites did suggest that charter schools have a higher student teacher ratio and a lower teacher to administrator ratio. Although this evidence is not conclusive, it does lead to further questions about charter schools and the impact of the autonomy they have.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Future Research in this Area

With charter schools continuing to open in North Carolina, there is a need for further research. There were some differences in staffing identified in this study that have the potential to be explored further through additional studies. The researcher recommends further research that focuses specifically on the effectiveness of charter school teachers and the teacher turnover rates in charter schools. In this study, the researcher found some evidence to suggest that charter schools are not set up to serve all students. Hidden costs for families and an expectation of donations from parents have the potential to exclude economically disadvantaged students. Further research on both the demographics of charter schools and equitable access to charter schools is recommended. This study highlighted the differences in academic outcomes between the two types of schools; however this research did not focus on why parents and families chose charter schools or magnet schools. Further research is recommended to identify the factors that play a significant role in school choice. Finally, this study did a comparison that was based on the compilation of data from a group of charter schools and a group of magnet schools; however, individual school results can vary greatly. Further research is recommended to identify specific factors, such as academic programs or teacher experience level, that are found in successful magnet and charter schools.

Recommendations to the District

Recommendation one. The researcher recommends that the district use this study to better inform the community about magnet schools and charter schools. The results of this study have the potential to be used to market magnet schools to parents in an effort to recruit students back to the district and retain the students that are currently in the district. It is in the best interest of the district to recruit and retain students from a funding perspective. This study provides statistical evidence that magnet schools have better academic outcomes than charter schools. Academic outcomes are likely to be a factor that parents consider when making the choice to attend a specific type of school. Hastings and Weinstein (2007) found that when parents receive information about school performance, they are significantly more likely to choose the school that is performing better.

Recommendation two. Consider expanding the magnet school choice options within the district. Since magnet schools are performing better than charter schools, the creation of additional magnet options may be what is needed to retain more families in the district. More magnet schools and programs would create greater access to a variety of quality programs so that all students have more than one good choice option. Also, the researcher recommends that the district consider magnet feeder patterns in all areas to allow students to continue with a magnet program from elementary school to middle school and from middle school to high school. Finally, considering the history of magnet schools and the role they played in desegregation (Minow, 2011; Davis, 2014), they have the potential to be a key factor in the current student assignment discussions within the district. The researcher recommends that the district consider the use of magnet schools as a tool to create stronger and more diverse schools throughout the district.

Recommendation three. Based on the student achievement results, magnet schools are performing better than charter schools with the majority of subgroups. However, students with disabilities had inconsistent academic outcomes in both magnet and charter schools. Although there is little research on students with disabilities in magnet schools, there is some research to suggest academic programs, such as a STEM focus, can be beneficial for students with disabilities if implemented to meet their needs. In a study on teaching computational thinking and computer programming to students with disabilities Israel, et al. (2015) recommended specific strategies, such as using multiple representations of concepts and multiple ways of engaging students, to give students with disabilities the opportunity to succeed in an academic area where they are typically underrepresented. The researcher recommends that greater support be provided to magnet schools to work with students with disabilities in achieving greater academic success. This support may include professional development for magnet school teachers and the addition of support staff to work with students with disabilities that are enrolled or want to enroll in magnet schools.