Six months ago, I was thrilled to become an intern in a second grade classroom. I have wanted to become a teacher since my early childhood. I felt like this would be the perfect opportunity to become familiar with the classroom from a teacher’s perspective.

Today, as I look back on those six months, I am questioning my willingness to become involved with public education which is being neglected and misunderstood by policymakers in Raleigh.

As a second grader, my curiosity and excitement for exploring classroom material was routinely encouraged. I would peer along the edge of my teacher’s desk as I would fire away questions and observations about the day’s lesson. I felt like Nancy Drew. And the extra nurture and care my teacher was able to give me in answering those questions, proved to effect my development in a number of ways. It was through those earliest experiences that I developed my ability to critically think and formulate unique ideas.

Compared to what I observed as an intern, I found that my second grade experience is no longer familiar behavior among eight-year-olds. The students’ natural curiosity is still present however, the students are not encouraged to act upon it. The absence of curiosity both on apart of the students as well as the fostering of said curiosity by teachers, perplexed me for the first several weeks of my internship. I could not fathom how something as natural and dominant as a child’s curiosity could be overpowered.

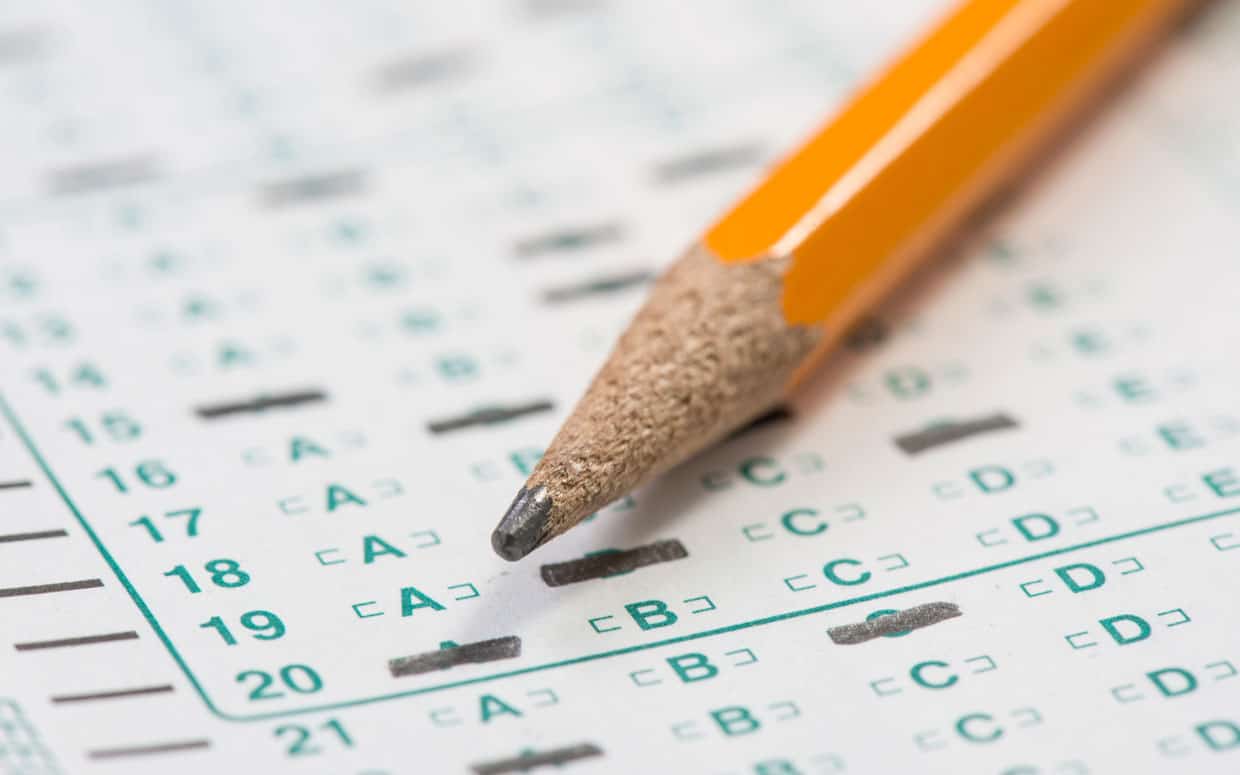

My realization of what was the true nature of the black hole sucking the curiosity from second graders, finally came to me as I sat through my first “practice assessment.” Practice assessments attempt to replicate the content and format of End of Grade tests.

Students were asked to work through the test in 90-120 minute portions. The teacher sternly proctored the students, speaking loudly “misadministration” if the child squirmed in the least. The process was truly devastating for everyone involved. Devastating in the sense because so much intellectual and emotional growth carefully nurtured over the previous six months, was largely nullified during that 90-120 minutes.

For several months, I worked with a small group of students and they excelled with the one-on-one attention they were not used to receiving. Lack of teacher assistants, large class sizes, and frequent lack of attention at home combined to create a classroom population starving for one-on-one attention. I watched the students grow in their writing, reading, and social skills.

All of the vast improvements they made came to a halt the day they began their exams. Some of them froze up and became unable to process the tediously-worded equations. That day I watched an eight-year-old boy on the verge of tears as he struggled with the exam, and that was the day I swore off becoming a public school teacher as it currently stands in North Carolina.

These tests were also proving to be the culprit behind the monotonous school days. The teachers I worked with gave their all to make each day interactive and exciting, but often they expressed how overwhelmed with pressure coming from EVASS and the state tests.

The students were constantly reminded that these scores counted a great deal as to whether or not they would go on to the third grade. They also count a great deal for the teachers who are scrutinized and judged by the test scores. Students were so overwhelmed by testing anxiety that they told me that they “didn’t want to to go to the third grade because that was the testing year.”

Midway through my internship, I decided to conduct surveys to determine whether testing was truly as big of an issue that I suspected it was. A Google form document was sent out to all of the teachers in this K-4 school. Within two days I had sixteen responses all of which were submitted anonymously. A common theme emerged from their disconcerting yet eloquent responses.

“Shutting down classroom instruction to test is very frustrating knowing that the kids are facing E.O.G.’s at the end of the school year.”

” The tests are challenging because they are “one size fits all” and we know students aren’t the same.”

“Today we spend a lot of time testing, progress monitoring and talking about the test. I don’t ever recall being stressed about a test as a kid the way my students are stressed about the EOG’s. Tests were just something we did and were never a big deal. At 8 years old I never had to worry that I wouldn’t pass third grade because of one test. It’s just too much pressure on the students and on the teachers.”

“The students today are tested entirely too much. Not enough time is allowed for children to learn through exploration and classroom experiences.”

“I feel that the educational environment has shifted to more testing-centered instruction, instead of more student centered learning which seemed more prevalent when I was in elementary school.”

Collectively, the 16 teachers who returned the surveys estimated that they spent a total of twenty percent of each month administering tests and conducting “progress monitoring.” After speaking with the teachers I decided to distribute surveys to all of the third and fourth graders to see if their answers were similar to what I observed in the second grade. I asked the third and fourth graders without prompting them beforehand, to ensure elimination of my possible bias towards their response.

When 135 students responded to “What is your least favorite part about coming to school?”

The top three responses were:

- Math (26)

- Testing (23)

- Going to school (14)

When asked “What would you like to learn about at school?” Thirty of the students responded by saying “animals.” Several of the other students had a nature-themed response. Other answers included “art, robotics, physics, or vocational interests.”

Through my surveys and observations I have found the over-dependence on standardized tests to be deeply disturbing. The psychological impact on six, seven, eight, and nine-year-olds should be a concern for all parents of young children currently enrolled in a K-4 public school. It should also be of great concern to the General Assembly, the Superintendent of Public Instruction, the State Board of Education, as well as local school boards.

Students coming from these high anxiety school environments, eventually become adults living in our communities. Shouldn’t it be of our greatest concern to make sure students are receiving intellectually stimulating content that stimulates them to becoming better leaders and citizens?

And what happens to the little girl who just wants to peer along the edge of her teacher’s desk, asking question after question without concern to whether she will be tested on the content? And what about the teacher who wants to foster curiosity in that little girl but who feels that she doesn’t have the time to focus on content that will not be tested? And what about the recent high school graduate who had a lifelong career goal of being a second grade teacher but who refuses to participate in pointless amplification of anxiety and the stifling of an eight-year-old’s curiosity?