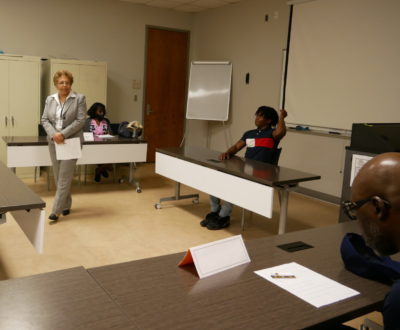

Before Bill Frye met his current class at Richmond Community College (RCC), he was thinking of retiring. After ten years teaching the HVACR (HVAC and refrigeration) program — plus a pandemic — he was ready. Then he met his students.

“I changed my mind,” Frye said. “I told my wife, this is a good group.”

This group feels the same way about Frye.

“Anything that we need help on, he’s willing to do it, no hesitation,” said James McLean, a first-year student in the program. McLean has seen friends find success in similar industries and wants to go straight to work after finishing the two-year associate degree program.

The industry demand “has skyrocketed,” Frye said.

“I have contractors and companies call me every year for employees, and I have more people wanting them than I have to send to them,” Frye said.

The college is working to place industry demand at the forefront of all of its offerings, said RCC President Dale McInnis. Knowing there is “light at the end of the tunnel,” McInnis said, plus a personalized experience with faculty, helps students succeed.

RCC serves Richmond and Scotland Counties, which are both considered Tier 1, a designation the state Department of Commerce gives to the most economically distressed counties.

“It’s all about breaking that cycle of poverty,” McInnis said.

Providing opportunities for economic mobility in the area is personal to McInnis, who grew up on a Richmond County farm — and whose family has been in the county since 1790.

“I’m very lucky to be able to help people that you were at school with, and they’re your neighbors, and that you go to church with, and seeing their kids and grandkids come up and ask for you, is very special,” he said. “A lot of the things we do don’t happen overnight, and you plant seeds that take a long time to grow sometimes, but we’re committed.”

Those seeds have an impact. A recent economic impact report found one out of every 21 jobs in Richmond and Scotland Counties is supported by the college’s activities and students. In 2019-20, the college added $88.2 million in income to the area, the equivalent of 1,613 jobs.

“This contribution that the college provided on its own was larger than the entire Construction industry in the region,” the report’s executive summary states.

State impact

When McInnis thinks about the seeds the college has planted in recent years, the impact goes beyond the income and spending factored into the report.

They’ve built a full campus in Scotland County, as well as a center in downtown Rockingham. They’ve found ways to better utilize the scenic grounds, auditorium, and outdoor amphitheater for public events and concerts. They’ve started programs that attract people from across the country, like the electric utility substation and relay technology program. And McInnis has looked to change the rules at the state level.

“You can’t divorce the work at the local level with the work at the state level,” he said.

Putting industry demand first meant changing how courses were funded. In many cases, the industry demand means offering degree programs like Frye’s. The electrical substation program, the only one of its kind in the state, is also a degree program.

“The folks in the utility industry said we need this to be a two-year degree, we need you to teach trigonometry, we need them to be exposed to English and the humanities, we need them to have a pathway to potentially a four-year degree,” McInnis said.

In others, it means offering noncredit courses referred to as “continuing education.”

All community colleges have both kinds of courses, but McInnis said curriculum courses have long been valued more. He has worked with the Association of Community College Presidents to push for legislative changes to work toward funding parity between the amount of funding colleges receive for curriculum and continuing education courses.

“What we’ve done finally is all the programs are valued the same, all the faculty are valued and treated the same,” McInnis said. “… Changing this model and having this balance where we’re making appropriate decisions for the right reasons has really I think redefined how we do business.”

McInnis pointed to a new partnership with Hendrick Automotive Group, whose leaders in Charlotte helped the college craft a noncredit 16-week course for students to earn an automotive technician certificate and begin working immediately.

The college has plans for a 15,000 square-foot facility, the Hendrick Center for Automotive Training, on its Hamlet campus. The college will be able to graduate 50 students a year, McInnis said, because of the continuing education model.

The college has similar programs for electric linemen and pharmacy technicians. It is also kicking off a Commercial Driving License program with a similar model.

He added that the college is working to address another barrier to continuing education — that those students are not eligible for financial aid — by focusing its foundation on scholarships for noncredit programs.

There are still some examples of curriculum courses being valued more, McInnis said, that he pushing to change.

“When you change the rules and modernize the rules, suddenly, you can adapt and evolve.”