I’ve been in the education field for nine years, serving six of those in a charter school. Recently, the North Carolina Teacher Voice Network, a division of Hope Street Group (which I am a part of), aggregated data on several key issues in teaching[1]. Among these issues, five key concerns about charter schools came out:

- Charter schools take resources from public schools

- Charter schools have no interaction with public schools

- Charter schools take students away from public schools

- Charter schools have different standards/curriculum, causing many students to be less prepared when they transfer to public schools

- Charter schools are perceived negatively by many traditional counterparts

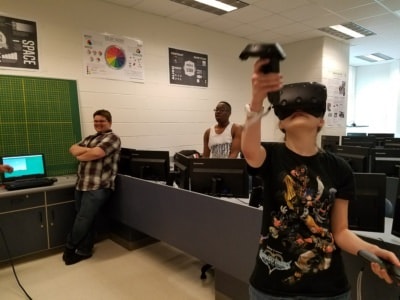

It’s a regrettable perception, because there are a number of fantastic charter schools doing innovative things[2] that are challenging our educational structures and concepts for the better.

The sad reality is that there are also many charter schools who are not providing quality and innovative education well[3], [4], [5]. Many of these charters are using their funding in highly questionable ways[6], creating inferior instruction in the classroom[7], [8], and only replicating their public counterparts without innovative practices. Let us be clear: for those of us who are passionate educators, and choose the route of charter schools, we recognize the incongruence brought about by failing charters. So, how can we work together to rectify the image the public has of us, especially the perception of our public education colleagues. I offer a two-part solution, which would require accountability for both traditional and charter schools.

Part A: Accountability through the process

Charter schools are required every five years (or ten years, in some instances) to revisit their original charter in order to assess compliance in finance, academics, and policy. I recommend that as a part of the charter application and renewal process, it become a requirement that charter schools must reach out and partner in some capacity with a traditional school. This can range from professional development partnerships between the schools, sharing best innovative practices, and teacher leadership opportunities.

This must be a two-way street, however. Charter schools could very easily reach out to schools in their area, with little to no response from traditional schools, especially those who are inclined to block off conversations with charters around them. Which is why we need an incentive.

Part B: Incentivized grants or funding for partnership

This one would require more creative efforts from outside resources, federal/local dollars, and investors of education. Imagine the buy-in that could be garnered if a funder offered financial assistance to schools who partnered together. This would encourage and enforce collaboration on a different level, since both schools would be incentivized to receive additional funding for their efforts in working together.

We, as educators, must begin to erase negative dialogue. Instead of pitting traditional schools against charter schools, we should work to navigate how we can create, collaborate, and innovate education for all students in our districts and our great state.