Share this story

- "How can community colleges reimagine, reface, and reshape their presentation to residents to make sure that they know this is the place where you need to go?" Dr. Kenyatta Lovett asked N.C. postsecondary leaders at an adult learners convening last week.

- "Our students and our residents, they're not rejecting higher education and workforce development," Dr. Kenyatta Lovett told N.C. community college leaders at an adult learners convening last week. "They're rejecting our version."

|

|

From fall 2012 to fall 2022, college student enrollment dropped by about 1.9 million students – almost 10%.

College enrollment has been declining since 2010 – due to factors like falling birth rates and rising college tuition, among others. Such trends were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, with community colleges hit particularly hard. Enrollment has since slightly recovered, but higher education institutions aren’t out of the woods yet.

College leaders must reimagine the access, engagement, and completion models at their schools in order to reach students moving forward, Communities Foundations of Texas’ (CFT) Dr. Kenyatta Lovett said at an adult learners convening in Greensboro last week.

“Our students and our residents, they’re not rejecting higher education and workforce development,” Lovett said. “They’re rejecting our version.”

Lovett, the managing director for higher education at CFT’s Educate Texas initiative, spent more than 16 years in higher education leadership in Tennessee, where he launched the state’s first apprenticeship office and worked as the former executive director of Complete Tennessee.

In that role, Lovett worked on Tennessee Reconnect, one of the state’s two initiatives to support adult learners. That project served as a model for N.C. community college leaders who launched N.C. Reconnect to enroll more adult learners across the state.

While working on Tennessee Reconnect, Lovett told event attendees last week, he quickly learned tuition was not the only barrier for adult learners coming to college. Many students wanted to know if the jobs they could get with new certificates or degrees would actually help them earn more.

And for students who did decide to enroll, financial pressures meant one unexpected cost – a flat tire, doctor’s visit, or broken appliance – could force them to pause their education.

“So when we think about the work ahead… we have to think about this with a sense of urgency,” Lovett said. “While we may be fine, the runway from which this thing can take off may not be as long as we give it.”

The opportunity

The pandemic highlighted a lot of new elements for higher education, Lovett said, that colleges need to think about moving forward – good and bad. After the pandemic, colleges must build quality programs, along with strong systems to sustain those programs in times of crisis.

First, Lovett said community colleges must move from aligning to braiding resources. In Texas, for example, Lovett and his colleagues quickly saw that pathways to successful outcomes did not often account for student challenges. They realized students were not often being handed off from one milestone to another, and that more work was needed to better serve specific adult student populations.

So what does it take for a student to reach a successful outcome in their pathway? Lovett outlined a few key findings:

- Advising is not a binary outcome. Community college is one part of a larger ecosystem – how are colleges shaping and sequencing advising for a long-term conversation with students? How are colleges meeting students with a variety of goals and needs?

- Credentials = currency. In other words, credentials are not a stopping point, but a stepping stone. In particular, credentials are helpful for students who have the experience, but not the formal qualifications.

- Employers engage in two distinct ways. Employers either act as true partners in the supply chain, or as a participant in the process. Community colleges need to work to identify and develop the true partners, Lovett said.

- It’s not college or career, but college and career. These conversations take place with each other, Lovett said, and make more sense the more they’re connected to career.

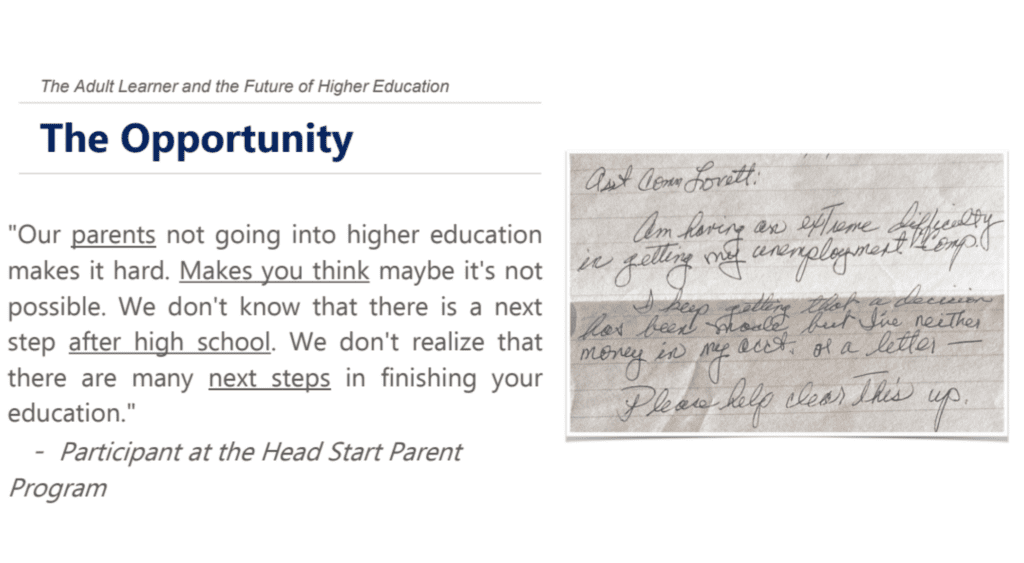

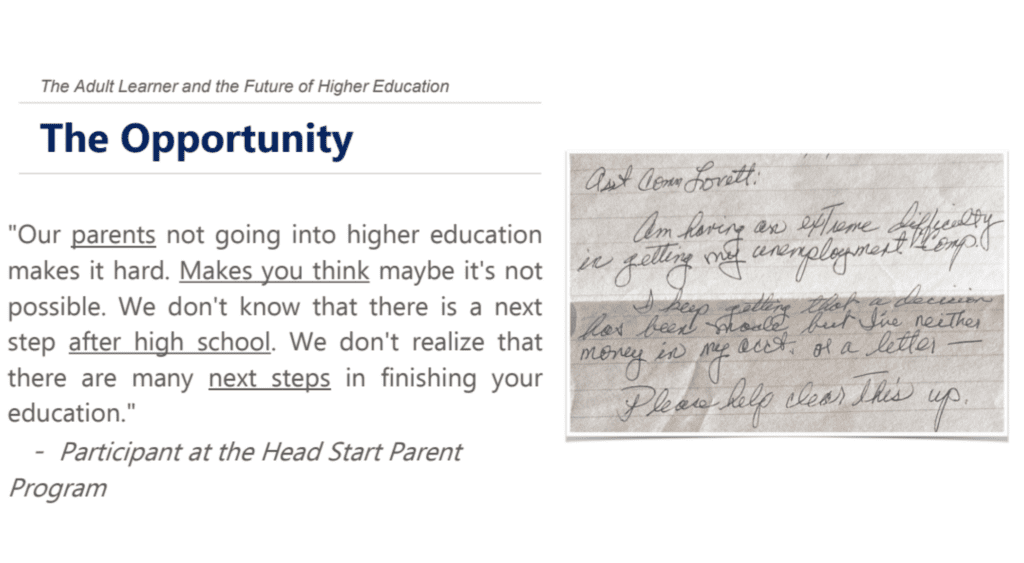

- The first door matters. Community colleges are not usually the “first door,” or first point-of-contact, for students learning about postsecondary options. First doors might be a nonprofit, food bank, or community organization. Because of that, how colleges engage with such organizations matters.

Colleges must also revise linear models designed for non-linear realities, Lovett said.

He challenged attendees with the following questions: What type of student is ideal for successful navigation through the higher education system? What type of student is not?

In many cases, higher education is not designed with the realities of adult learners in mind, he said.

The most influential factor for many adults is their family and children, Lovett said. Colleges should leverage that reality, rather than – intentionally or not – letting it remain such a large barrier for adult students.

He challenged community college leaders to think about ways to build systems, internal values, and policies “to successfully support non-linear realities” faced by many adults.

What does reimagining look like?

Where is the long-term opportunity to serve adult learners? Lovett sees several possibilities, in North Carolina and beyond.

First, community colleges must reimagine access and engagement.

For some students, that means viewing short-term credentials as career lattices, which can connect students to future education and employment opportunities. Credentials have many purposes, Lovett added, like economic value, along with mobility value and engagement value.

“Obviously the gold standard for state governments right now are credentials of economic value, and that’s good. But what about credentials of mobility?” he said. “What credentials actually can stack to lead to economic and social mobility? … And credentials of engagement, for adults especially, they may not be ready to dive deeply into higher education, but you may need to build their confidence that they can do it.”

Reimagining engagement also means shifting from viewing people skills as “soft skills” to “social capital.” Lovett noted that a lack of soft skills is not a deficit for the student, but a social capital they do or don’t have – and one community colleges can help develop.

Colleges must also “make our residents more mobile,” Lovett said, streamlining pathways while acknowledging prior experience and microcredentials students do have. He suggested shifting from “transfer” language to “credit mobility.”

The education market has shifted, Lovett said at the end of his keynote, with more education options available to residents than ever before. Those options include YouTube videos, stackable courses, and on-the-job training offered directly by employers.

If community colleges are the best place to offer job training and an entry into postsecondary education – and Lovett believes they are – then he said they must do a better job proving that to students.

“So there’s really an inflection point right now in higher education,” Lovett said. “How can community colleges reimagine, reface, and reshape their presentation to residents to make sure that they know this is the place where you need to go?”

Editor’s note: The John M. Belk Endowment supports the work of EducationNC, and sponsored the convening with EdNC.