For Dr. Chris Baldwin, his earliest and favorite memories of Nantahala School, a K-12 institution nestled in a gorge that has served a remote region of Macon County since 1961, happened on the bus. One while he was a student, and the other while he was driving a route during his time as a teacher.

His first recollection of the school he attended, taught at, and eventually became principal of involves the school bus, and the memory imbues his five senses. The smell of the bus, the grooves in the aisle, and the feel of the seats.

Later, when he was a teacher at that same school, he was in charge of scooping the students that lived up Wayah Road, which gains about 1,000 feet in elevation top to bottom and curves around Nantahala Lake. One morning, there was snow on the ground, and he picked up three students he still remembers by name — Diamond, Miranda, and Daniel Williamson.

The bus was just starting to warm up inside, with a blanket of white flanking the road. As the bus was coming back around the lake, the three family members began singing the folk song “Old Dan Tucker.”

“I thought, man, it’s hard to believe that I’m being paid for this experience,” Baldwin said.

Macon County, then and now

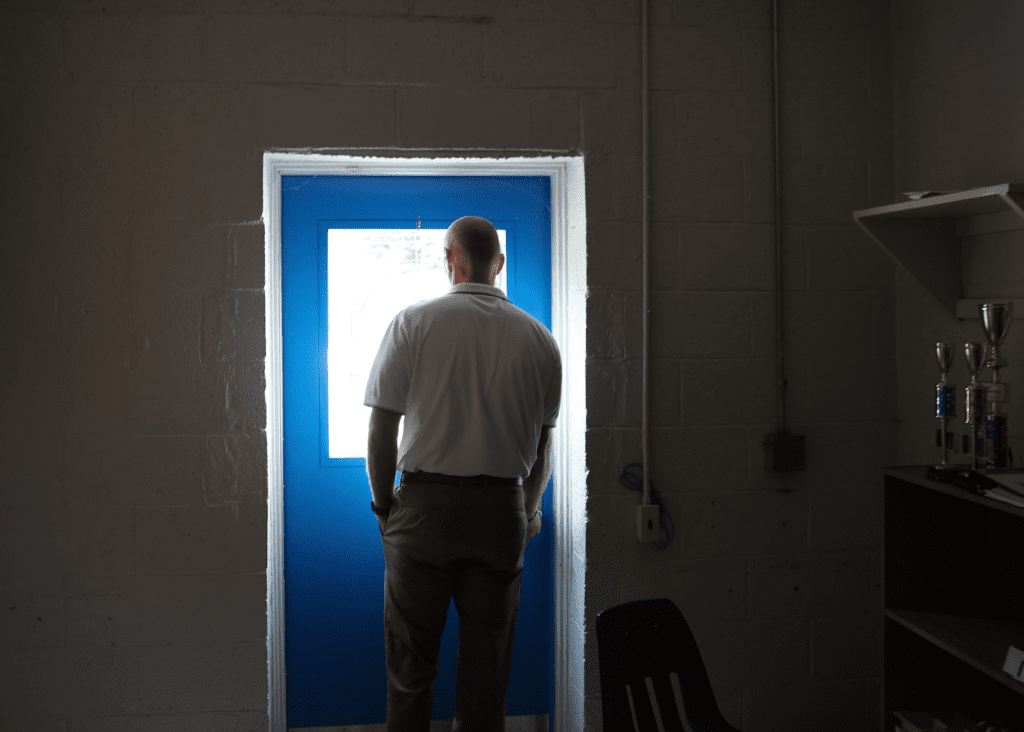

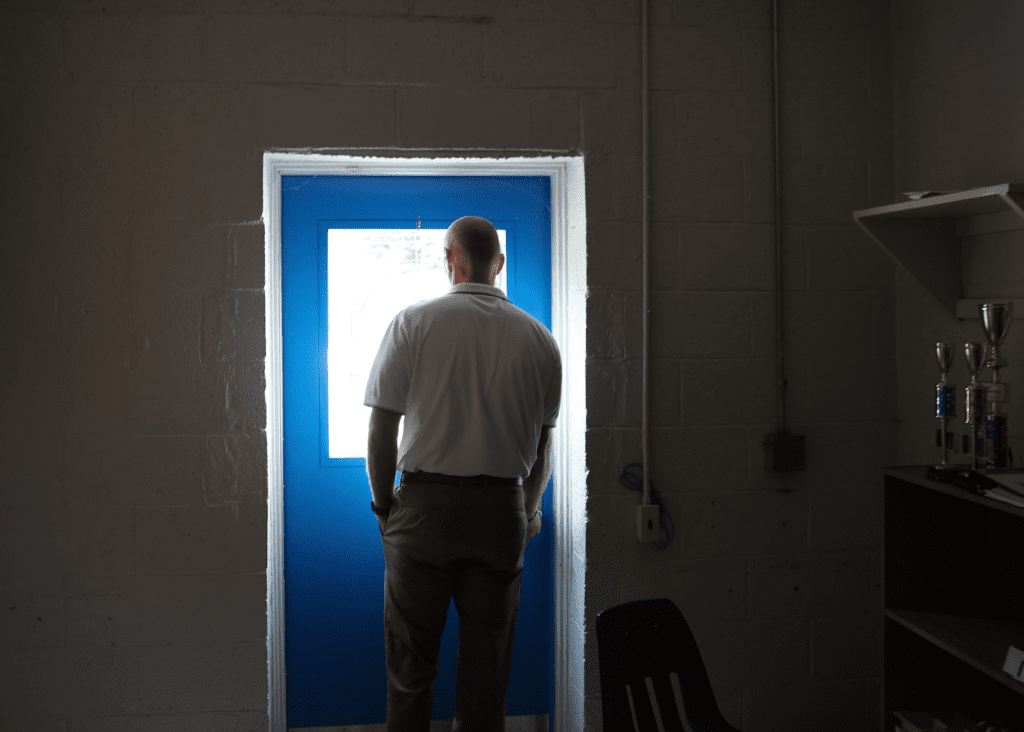

Baldwin has dedicated his career to education and his county. He grew up in the Nantahala community, attended its school, and then eventually returned to teach and became the principal. He went on to serve as the Macon County Schools superintendent for 13 years, before retiring officially in June of 2023.

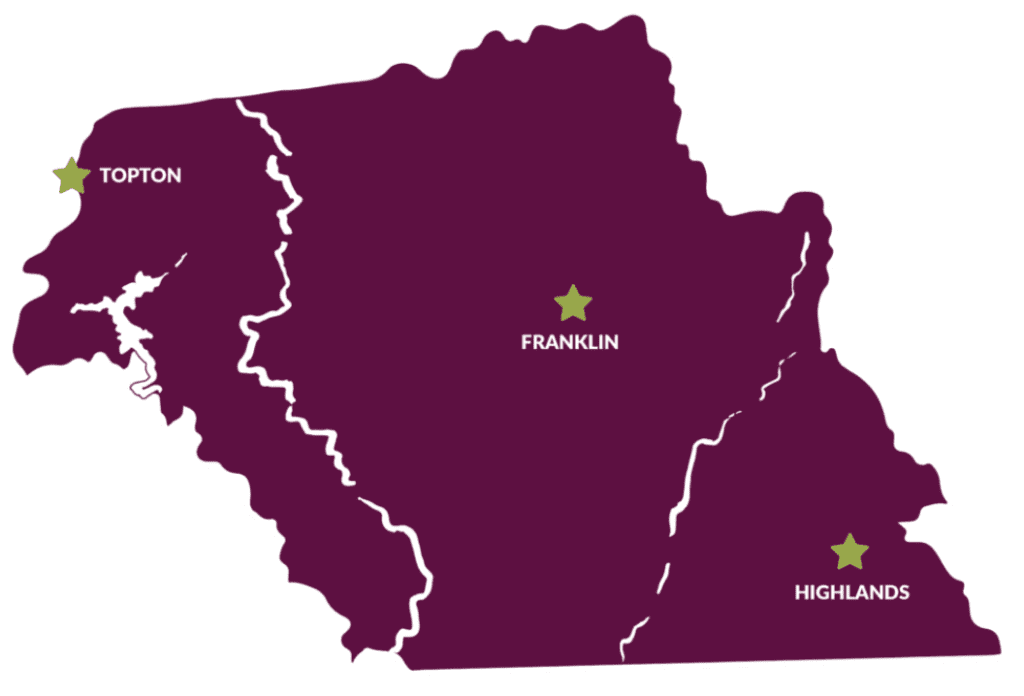

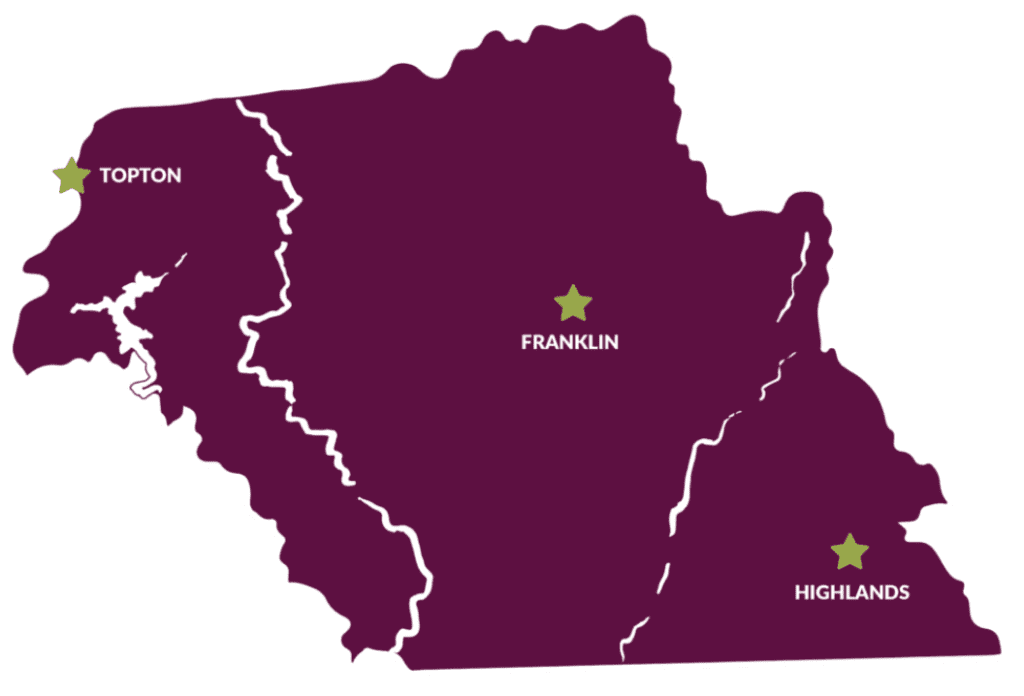

When asked to describe Macon County in his own words, Baldwin first points to geography. There is Highlands on the eastern side of the county, which was named America’s Best Small Mountain Town by Travel + Leisure magazine this year. And on the very opposite side in the far upper western corner sits Topton, where the Nantahala School lives.

In the middle lies Franklin, which he points out has four elementary schools that all serve different communities. The county is 520 square miles.

In terms of describing Macon County overall, just good people… Very different cultures across the county, but very supportive of young people. Very supportive of education. I think that over the past 20 years, we’ve probably seen, you know, some with school choice, some different avenues of support, but they still support education. And overall strong supporters of K-12 in Macon County. But it’s a rural, predominantly rural community (with a) strong work ethic. But just good people, good, hardworking people.

Dr. Chris Baldwin, Macon County superintendent from 2010 – 2023

Growing up in the region, he would notice how families migrate with the economy, and as principal at Nantahala, he saw this shift through an educational lens via enrollment. He attributes this to a combination of factors — the region’s history in manufacturing and historical land ownership.

In the early 1900s, he said people had larger families and owned a couple of acres in the county. Back then, during a recession, the district would see an increase in students because families who had moved away to take jobs in textiles in High Point, the auto industry in Detroit, or coal mining in West Virginia would move back to their familial homestead.

With the real estate bubble in the 2000s, Baldwin believes some families sold those homes, the pieces of property that had been in their lineage for generations, and when the recession of 2008 hit, those families didn’t have a spot to return to in Macon County. Couple this with job losses inside the region, he has seen enrollment rise and decline at various times.

He grew up working in tomato and tobacco fields, like much of his community. The adults he knew and parents of those friends worked in manufacturing. He said those things are gone now.

“We had more kids enrolled when we had more manufacturing. And that’s, you know, that was the big magnet for families in Western North Carolina was those manufacturing jobs — good jobs, steady jobs — that allowed folks to have stayed and lived here in western Carolina,” Baldwin said.

During his lifetime, he’s seen a shift away from agriculture and manufacturing and toward a burgeoning tourism and recreation economy. One of the closest businesses to the school itself is the Nantahala Outdoor Center, which boasts one million annual visitors.

Other major changes he has seen in his district are due to technology, and he doesn’t only mean in instruction. Nantahala didn’t have air conditioners until the mid 1990s. He said today the schools are equipped with geothermal systems, and there is AC in all rooms.

Those things have upfront costs and are expensive to maintain. Small schools have to adjust for those things in the budget, on top of new technology for instruction.

“I think technology has changed every community, rural (and) urban,” Baldwin said.

Something in recent years that has offered change in counties across our state is the expansion of school choice. This year’s legislative session included a vast expansion of private school vouchers through the Opportunity Scholarship program.

Baldwin shared his thoughts on the current movement, and what it could mean for Macon County families.

School choice, I think at face value, there’s nothing wrong with it.

School choice when it involves defunding public education is a problem. And I don’t think folks understand the impact that that choice has, you know, if you’re a family here in Nantahala, and you want to enroll your child in a private school, you know, you’re looking at $20 to $30,000 a year in a private school.

Public education in Macon County costs the taxpayer about $10,000 to $11,000 per child. And what you’re getting for that amount of money is a pretty good bang for the buck.

You know, I have to break it down for folks here in Macon County. You know, our budget was in the mid $50 million per year with 4,500 students. You know, that’s a lot of money for someone that grew up making $2 an hour hoeing tobacco and tomato rows.

You know, $50-plus million dollars is a lot of money, that’s hard for me to wrap my mind around. So to break that down, you get down to $50 million dollars for 4,500 kids per year, that works out to $10 to 11,000 per child, per year (in) 180 school days. That works out to about $55 to $60 per day per child.

You know, from what we provide students in schools in North Carolina, for $50 to $60 per day, is pretty tremendous. Starts with that yellow school bus picking those kids up in the morning, bringing them to a conditioned school building– its warm in the winter, cool in the summer, feeding them two meals a day, snacks, extracurricular activities, teach them to read, and write, mathematics. If they have vision problems, we can teach them Braille. If they have hearing problems, we can teach them sign language. (We offer) occupational therapy, physical therapy if they have mobility issues. And, you know, then just preparing them for college or for life for $50 to $60 a day, and folks are spending that much money to board a pet.

There’s folks that are telling these people that their kids, their child is not receiving a good education. You know, and research has shown that most parents are satisfied with their school. And that’s true in Macon County. They’re not satisfied with public education, but they’re satisfied with their school, what’s causing that?

There’s some misinformation out there. And we’ve got to do a better job of showcasing what we provide to kids at really minimal cost.

Dr. Chris Baldwin, Macon County superintendent from 2010 to 2023

From student to superintendent

As a first grade student, Baldwin can remember collecting coal on the playground and hiding it under his bed because he thought it was worth something. He started at the school in 1974, and the building was still heated by coal. When he came back as an educator, he found the room that stored the coal was converted into a classroom — one he would eventually teach in.

Baldwin graduated from Nantahala in 1986, attended Western Carolina University, receiving a bachelor’s in science and education in 1990, and returned promptly to his alma mater to begin work.

The year he started teaching, there were no students in the ninth grade, but four transferred a couple months into the school year. Baldwin went to Lowe’s, purchased a white board and some erasable markers, and set up his biology classroom on top of the stage in the school’s theater dressing room.

In 1993, he started teaching seventh through 12th grade science. During those years he was always coaching some sport — volleyball, cross country, or basketball — and driving a school bus. In 2001, he was named principal and served that post for nine years.

He finally left Nantahala in 2010 to become principal at the county’s largest high school in Franklin. It was a big change. For comparison, in 2023 Nantahala School has 84 K-12 students while Franklin High School serves 950 ninth through 12th grade students.

The organizing of the school day’s activities was also a lot more involved and fast paced than at his previous school. More students meant more of everything: more faculty, more course offerings, more extracurricular activities, more events, and more overall time on campus. Understanding the needs of each department was important to him.

He said the least challenging part of that new job was the students themselves.

The student body of both schools was just outstanding… A lot of differences in the community, obviously, from Franklin to Nantahala, but good people in both communities. The advantages are tremendous at both locations.

Dr. Chris Baldwin, Macon County Superintendent from 2010 – 2023

Baldwin was principal of Franklin High School from 2010 to 2013, and moved on only to become superintendent of Macon County Schools.

It is a special thing to have someone at the helm who has seen the ebbs and flows of their county for the last 50 years. Asking if he knows of any other person who attended their district from kindergarten to graduation, and eventually held all three positions of teacher, principal and superintendent, he’s says he can’t confirm, but laughs saying, “That’s probably a short list.”

Baldwin’s dedication to his rural district may be unique, but to him it isn’t. This is what people in his community do. He believes, “they care for one another, and they care about education.”