The John M. Belk Endowment and Durham-based nonprofit MDC have partnered to examine the patterns of economic mobility and educational progress in North Carolina to determine who is being successfully prepared for entry and success in the most economically rewarding sectors of the state’s economy. The report, “North Carolina’s Economic Imperative: Building an Infrastructure of Opportunity,” provides data and analysis on these trends and includes a close look at eight localities across the state. This week, EducationNC will be featuring the profiles of five of those communities.

You can’t talk about Wilkes County without talking about its long history of entrepreneurship. From a modest hardware store in North Wilkesboro grew Lowe’s, one of the largest home improvement chains in the country. Any fan of 1970s ACC basketball remembers the Holly Farms Chicken Player of the Game, but may not have known that every time that UNC’s own Phil Ford received that award it was from a Wilkesboro-based company. And of course, driving into the county on the Junior Johnson Highway is a reminder that entrepreneurship in the form of moonshine running and stock car racing is part of the county’s history as well.

The legacy of these and other businesses in Wilkes County is just that: a legacy. In 2003, Lowe’s took its headquarters to the big city, or at least to the booming Charlotte suburb of Mooresville. Holly Farms was taken over by Arkansas-based Tyson Foods back in 1989. And the only tangible reminder of Junior Johnson and his racing friends left in the county is the hulk of an abandoned speedway sitting just off Highway 421.

So what does a community do when it its economic base is stripped? What do you do in the face of declining population and massive job loss?

“It hurt our pride, especially when you see the racetrack sitting over in North Wilkesboro deteriorating. It was a similar feeling when Lowe’s left,” Linda Cheek, the president of the Wilkes Chamber of Commerce says. “But you have to hitch up your pants and say, ‘Let’s go.’”

“But you have to hitch up your pants and say, ‘Let’s go.’” — Linda Cheek, president, Wilkes Chamber of Commerce

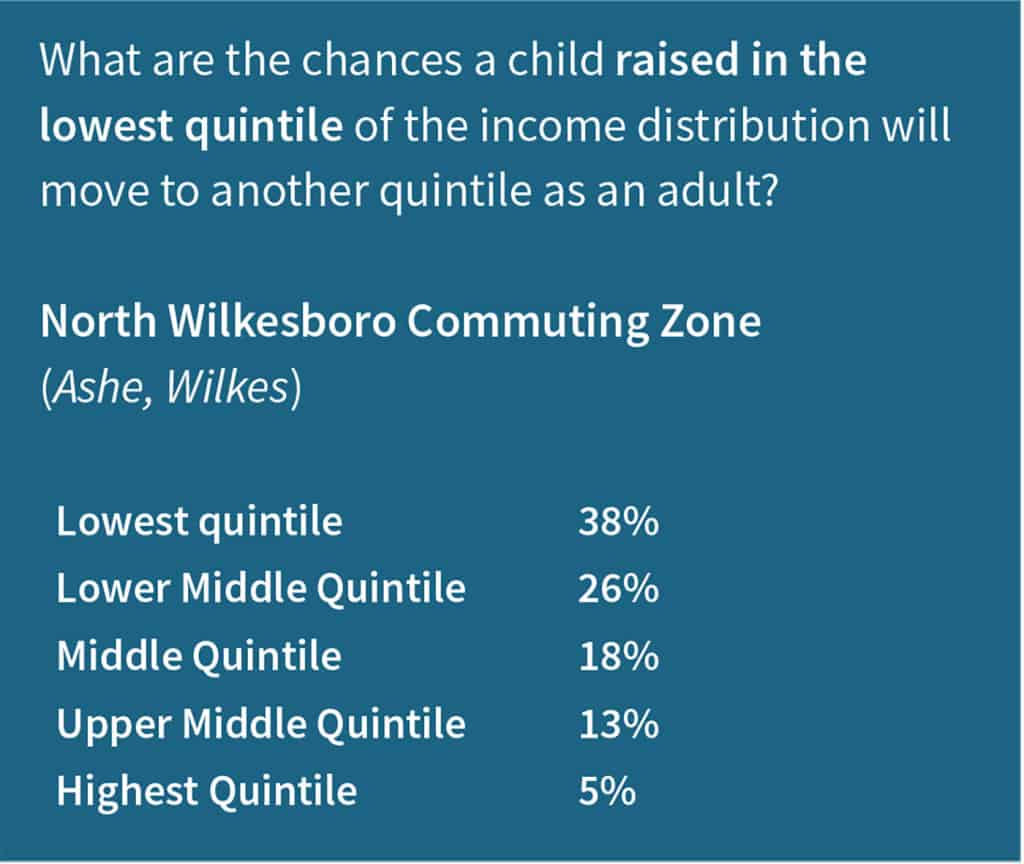

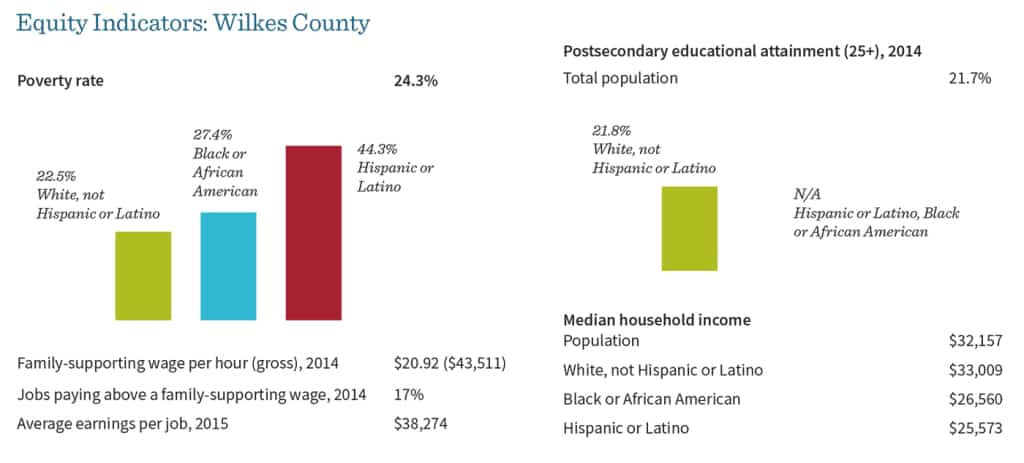

Indeed, connecting workers to this new economy is one of the significant and pressing challenges the county faces: how do you make sure the county has the workforce to grow the economy? How do you fill the skills gap to ensure that the prospect of economic growth—be it in manufacturing or in other sectors—is met? The county faces issues similar to those in the rest of rural North Carolina, especially regarding economic mobility. These regions must ensure that efforts aimed at providing good, homegrown opportunities for the county’s best and brightest reach all segments of the population. Rural communities want those opportunities to appeal to young people who leave to pursue an education so they’ll come back to pursue their chosen professions.

“I have a huge concern for people who just have a high school diploma,” says Mark Byrd, interim superintendent of Wilkes County Schools. “Fifteen years ago there were jobs for those individuals at factories and they could have a successful life. There are so few of those jobs available now.”

Hardin Kennedy, chair of transportation technologies at Wilkes Community College, puts an even finer point on it. “We have a top education for the top 14 percent of the county, but what about the other 86 percent?” There are vexing barriers that impede mobility for these 86 percenters. These include intergenerational poverty, lack of public transportation, the cost of internet access (which is increasingly needed to find jobs and meet educational requirements), and a deadly drug problem. Wilkes County has had consistently the largest number of methamphetamine labs in the state; 50 labs were raided in 2013.1 Employers frequently comment on the inability to hire workers due to drug test failure, making the cost of illegal drugs stretch beyond the personal to one with widespread economic impact.

“We have a top education for the top 14 percent of the county, but what about the other 86 percent?” — Hardin Kennedy, chairman of Transportation Technology at Wilkes Community College and a member of the Wilkes County School Board

“We see hopelessness among a lot of parents,” says Donna Cotton, director of secondary education at Wilkes County Schools. “Parents can’t see past a job at Tyson for their kids and even a job at a call center might be beyond their reach because it requires having nice clothes. We need to show kids there’s something else out there.”

“Parents can’t see past a job at Tyson for their kids and even a job at a call center might be beyond their reach because it requires having nice clothes. We need to show kids there’s something else out there.” — Donna Cotton, director of secondary education, Wilkes County Schools

As the region wrestles with these multiple challenges, it has embraced the idea of cooperative and collective solutions. Indeed, while the entrepreneurial spirit may have been the defining characteristic of Wilkes County in the 20th century, the first part of the 21st century is about working together to develop systemic strategies to connect more people to the education-to-career continuum. That means bringing business and industry to the conversation, but it also means public schools, the community college, and local governments have had to take action to promote effective policy efforts. Most of these efforts have focused on preparing a new workforce to both attract new businesses to the county and support new entrepreneurial ventures.

In some ways, the example for collaboration came from the closer relationship between North Wilkesboro and Wilkesboro. The towns share equipment on a regular basis and even have joint council meetings several times a year, an unheard of practice just a few years ago.

“We know we’ve got to work together to move forward,” says Wilkes County Manager John Yates. “We’ll go backward if we don’t.”

“We know we’ve got to work together to move forward. We’ll go backward if we don’t.” — John Yates, manager, Wilkes County

That spirit of collaboration extends to a renewed focus on getting the business community involved in worker training. The community college, Economic Development Council, and school system created the Business Industrial and Educational Forum (BIEF) to explicitly explore how to produce better qualified employees for local industry. While these industry councils by themselves are not uniquely innovative, having industry look at systematic strategies with people from postsecondary and the K–12 system is a breakthrough for Wilkes.

BIEF’s efforts have led to some innovative programs, including a teaching externship. In this program, teachers from the county’s five high schools are paid a stipend to spend a day with a local employer to learn about what the company does and what technical and workplace skills are necessary for the industry.

The collaboration modeled in BIEF is apparent between the local schools and Wilkes Community College. An example of the deep partnership is the new Project ADMIT (Advance Development in Manufacturing and Technology) which expands STEM-related instruction and opportunities for high school students. Project ADMIT will construct facilities at local high schools to accommodate the equipment and technologies to give students the training they need to be matched with employers in the region. Instructors for the program will include, at least initially, those from the community college until the school system can bring on full-time instructors at each of the high schools. Students who participate in these expanded career education programs can receive college credit, giving them a leg up as they pursue a postsecondary credential. The effort is funded through a variety of philanthropic sources such as Golden LEAF, government sources such as the Appalachian Regional Commission, as well as contributions from Wilkes County businesses.

President Cox sees programs like Project ADMIT as the solution to the critical economic challenge facing the region: growing or attracting businesses in a county where, traditionally, educational expectations have been lower. “It’s a bit of a chicken and egg scenario,” he says. “If we want to attract high-wage manufacturing we need a high-skilled workforce, but there aren’t necessarily those jobs here yet to encourage students to pursue these programs. To sustain these programs, we have to keep students coming in. We can’t build a program for two students a year.”

Much of the Project ADMIT focus is on preparing a new workforce rather than addressing the needs of incumbent or dislocated workers.

Marty Hemric, who retired as school superintendent in the fall of 2015, agrees that the challenge is making the connection between education and employment. “There is the real perception that we are educating people to leave— it’s not an accurate one, but a real one,” he says. “What we are doing is changing the mindset to get kids into more curriculum pathways by working with Wilkes Community College and local businesses, to give students awareness of the opportunities that are out there [in our community].”

Again, Hemric and others point to the collaboration with the college and businesses as a key to developing the programs. New programs like Project ADMIT developed through frequent conversations between the institutions in a variety of settings; they are not one-off programs created by a committee working in a silo.

“It is important to have cross-enrollment of entities and individuals on local boards,” Hemric says pointing to BIEF, the EDC, and the local hospital boards as examples where individuals can have conversations relating to local workforce challenges. “These shared conversations are critical.”

“It is important to have cross-enrollment of entities and individuals on local boards.These shared conversations are critical.” — Marty Hemric, former school superintendent, Wilkes County

Indeed, Hemric says that one reason Project ADMIT received funding was that it was not seen as a school project but as a community-wide effort.

Though the relationship between local community colleges and K-12 systems is sometimes difficult, that is the not the case in Wilkes. “It’s not my students or your students; we’re looking at all students as our students,” Superintendent Byrd says. “We’ve done an unbelievable job of eliminating that notion in Wilkes County.”

Another example of the collaboration comes from the active participation of local philanthropy, which has its roots in the economic history of the region. Several prominent families associated with Lowe’s stayed in the county even after the company moved its headquarters and have contributed to efforts aimed at increasing the economic vitality of the region. For instance, the Leonard G. Herring Family Foundation recently gave substantial funding to open a new health science building at Wilkes Community College. At the building’s dedication, it was clear that the foundation sees the college preparing people for work in the health-care industry as critical to encouraging economic mobility.

“We live in a low-income area with too many people in poverty,” said Lee Herring, representing the family. “The only dependable way out of that circumstance is an education leading to a job paying a family-supporting wage. With a two-year degree earned in this building, you are giving them an opportunity for a better life, to have a higher standard of living than their parents, and the means to support a family.”2

There is much underway in Wilkes County aimed at preparing individuals for work that can pay beyond a family-supporting wage. In addition to Project ADMIT plans, there are efforts to introduce more STEM courses into the middle school and high school curriculum and a program called Skills USA that allows school-age competitors from Wilkes County to compete and win national competitions on a variety of technical skills. All these efforts share the common commitment to collaboration and their current and projected success reflects that spirit.

But the community recognizes that there is a lot of work left to do. And it also recognizes that its programs may not be reaching the most difficult to reach—the persistently poor. If, as Kennedy at Wilkes Community College asserts, the county is already doing well on reaching the top 14 percent of students, the programs where the county is placing its next bets focus more on the next 30–40 percent of students, those who have shown some academic promise. These academically oriented programs are geared to identify students who may have an interest or aptitude for technical careers, but who have not yet had the chance to explore these opportunities. There are not as many programmatic efforts geared toward the bottom 20 percent or, perhaps just as concerning, on those who have lost their jobs and are now disconnected from employment. Projects to meet the needs of the most low-income residents are primarily through the United Way’s efforts at crisis management and relief, rather than addressing systemic causes of poverty.

Most of the collaborative efforts have focused on the future workforce rather than on retraining workers who may either be working in non-family-supporting jobs or have been disconnected from the workforce. Certainly, many of these individuals can reenter the education pipeline through Wilkes Community College, but the emphasis again is on finding a path for young people to enter the workforce.

And perhaps the focus on collaboration and cross-pollination of boards and committees has created another kind of silo when it comes to determining where the county’s emphasis should be. Groups such as BIEF that have been so instrumental don’t include active representation from low-income communities. It is not clear where the voice of those below the poverty line can be heard in making critical decisions for the community. Wilkes, of course, is not alone in this, but as the community seeks ways to lift people out of often dire economic circumstances, it may look for ways to encourage active participation from those not always included in shaping the community’s future.

Certainly the collective will to enact change in the face of trying circumstances is here. As Allison Phillips, executive director of the Wilkes Community College Endowment Corporation, puts it: “We keep going here. We get around our obstacles.”

“We keep going here. We get around our obstacles.” — Allison Phillips, executive director, Wilkes Community College Endowment Corporation

NORTH CAROLINA’S ECONOMIC IMPERATIVE: BUILDING AN INFRASTRUCTURE OF OPPORTUNITY

Part 1–Introduction

Part 2–Cultivating aspirations: Vance, Granville, Franklin, and Warren Counties

Part 3–Partners at the speed of trust: Guilford County

Part 4–Recovery through collaboration: Wilkes County

Part 5–Landscape defines opportunity: Western North Carolina