This is Part Three in a series examining the residency laws of North Carolina, the new RDS system in place to process applications in compliance with the laws, and the experiences of community colleges who feel the RDS system has become a barrier to their students. In Part One of the series, we looked at residency laws and why residency matters. In Part Two, we chronicled the experiences of community colleges and its applicants. Now we take a deeper look at RDS, how it was built, and what it is intended to do.

The challenge laid down by the General Assembly was — quite simply put — a big one. Inconsistencies, which became public when a student sued after receiving contradicting residency determinations from two North Carolina universities, created a stir — and the legislature wanted change.

“It was embarrassing that they had made these different decisions,” said Elizabeth McDuffie, executive director of the State Education Assistance Authority (SEAA). “It brought a spotlight to, when you assign this and tell campuses everybody’s responsible for their own, how they follow through on it could be different. That was where the inconsistency began to come to light.”

Under SEAA’s guidance, law makers asked state agencies to collaborate, consult a 33-page manual that interpreted state residency law, solicit input and from the 16 UNC System schools, 58 community colleges, and 40 independent schools, and combine the myriad residency determination processes occurring at 114 different institutions into just one process.

And to make sure the single process got the residency determination right.

With such an immense task, an advisory committee was formed and immediately got to work. But where would they start?

“You begin with the law,” said Gwen Canady, who is chair of the working group that manages RDS.

What became the finished product has drawn criticism from community colleges for making residency determination harder for their students than it was before. But RDS officials believe they answered the call laid down by the general assembly. From their perspective, they have created the one-stop solution that the legislature wanted, and made it more convenient and quicker for applicants to learn their residency status.

“RDS today is a byproduct of a lot of input,” Canady said. “I’m a very strong proponent. It makes good sense. It makes good sense to the citizens, it makes good sense to the parents, and to the high school students. And it’s definitely on us to make it as simple as possible so that nobody feels like it’s a barrier.”

But it starts with the law. For, after all, the law is where RDS was born.

When the first legislation passed in 2013 to commission a study into a coordinated approach to residency determination, the General Assembly tasked the SEAA with heading the initiative. They also called on certain state agencies to cooperate with the SEAA in electronically verifying evidence submitted in an online interview and asked for an advisory committee to be set up. This group included representatives from the UNC System, the community college system, and the independent institutions.

In 2014, around the time when the group reported back to the legislature, the advisory group was formalized as the Higher Education Collaborative Advisory Committee (HECAC), and Canady was asked to chair.

“When an idea comes forth or a problem comes forth, this group rolls up its sleeves,” McDuffie said. “It’s not a ‘Y’all fix this.’ It’s a ‘How do we fix this?’”

Under HECAC’s lead, about 1,400 people across system offices, state agencies, campus leadership, campus staff, subject matter experts, high school counselors, and student advocacy groups were consulted before creating and implementing the Residency Determination Service, known as RDS.

RDS aims to use conversational interview technology to customize questions asked of a student based on the student’s situation. The system is designed to ask as few questions as necessary to determine a student is a resident and ask as many possible before determining a student is a non-resident.

At the completion of the interview, RDS provides the student with a Residency Certification Number (RCN) and a determination (resident or non-resident). Students provide the RCN to institutions as part of the admission process. RDS also informs financial aid agencies and institutions so they know about students’ eligibility for state grants.

Now, RDS officials say, a student has to complete only one residency interview no matter how many schools they apply to, and they can get their determination in near real-time.

“Our goal is for it to be a consistent and accurate determination for everybody that desires to seek residency in North Carolina,” Canady said. “That’s the overlying thing, is that there is one place that a student can go and get an accurate determination. And we have tried to make it as simple as possible within the law that we have.”

RDS became operational in December 2016. The roll-out was planned in phases, with independent schools first, UNC System schools in early 2017, and all community colleges online by October 2017.

The institutions — across the board — were anxious.

“The UNC schools did not go into this willingly,” McDuffie said. “They were all very concerned. Nobody wanted to lose control over their decision-making. And it went really well.”

The UNC System institutions laud RDS for streamlining the process, creating more time for their admissions staff to focus on more students, and for taking the determination off their plate — so the particular UNC school is not the one delivering bad news in the case of out-of-state determination.

“While not being particularly thrilled with the idea, once it was implemented and they saw how it worked, they’ve come along,” McDuffie said.

For the community colleges, it was not such a smooth transition. Unlike the four-year universities, the community college student is more likely to have a non-traditional background and family situation. And they may also need more “hand-holding,” as one community college president put it.

For that reason, Isothermal Community College’s Sandy Lackner wonders if leaving it in the hands of the individual institutions – as residency was determined before – would not have been better.

“There wasn’t a huge problem from boots on the ground perspective, from the frontline,” said Lackner, discussing the pre-RDS process. “There was confusion, I’ll be honest with you. There wasn’t sufficient training. But would it cost a million dollars for us at the community college and university systems to have quality training?”

To them, nothing should make the process of getting into community college harder. Their mission is to take any person, to take them where they currently are, and to take them as far as they can go.

“I admire that,” McDuffie said. “They’re dead-on right, aren’t they? It’s admirable, and it’s a good goal.”

Yet, the legislature requires RDS — and so McDuffie and her team focus on improving it. RDS officials said they understand that community colleges still find issues with their applicants going through the online interview. They are in communication with the community college system and say they are actively working on concerns as they come up.

“They have kept us fully informed on what they’re doing,” McDuffie said. “I don’t think we’re taking sides here. We’re hearing them. And, certainly, trying to figure out how do we address their concerns and their students’ concerns.”

According to SEAA, as of last week, 623,530 interviews had been initiated on RDS. Of those that finished the process, 86 percent were determined as residents, 12 percent non-residents and 2 percent fell under military exception. But, also, 6 percent of those who started an RDS interview “stopped-out,” meaning that they did not complete it.

It’s those that “stopped-out” — in addition to many students that schools learned intended to stop-out before receiving help from admissions — that raise community colleges’ concern.

A major issue that has arisen is the legal presumption that a student lives with their parents if they have a living parent. Many community college applicants complaining about the system raised this so-called parents’ domicile concern, because they were estranged from their parents or, while the student was a U.S. citizen, the parents were not. Why, they wondered, should their parents’ information matter when they can clearly show they have lived in North Carolina for several years and intend to stay?

“But that’s where the law starts, and so that’s where we start with RDS,” McDuffie said. “We’re trying to make it get at what the law is actually requiring.”

And where it can, RDS also tries to introduce some leniency as permitted by the law.

As discussed more in Part Four of this series, released tomorrow, RDS was tweaked after release to limit those presumed to be living with their parents to applicants under 24 years old. Applicants 24 and older do not have that presumption. In fact, RDS officials say, they have designed it so that married, veteran, and financially self-sufficient applicants do not, either.

And for those under 24 who are independent from their parents or guardians, but nevertheless are confronted with RDS questions about their parents’ domicile, RDS has other built-in options.

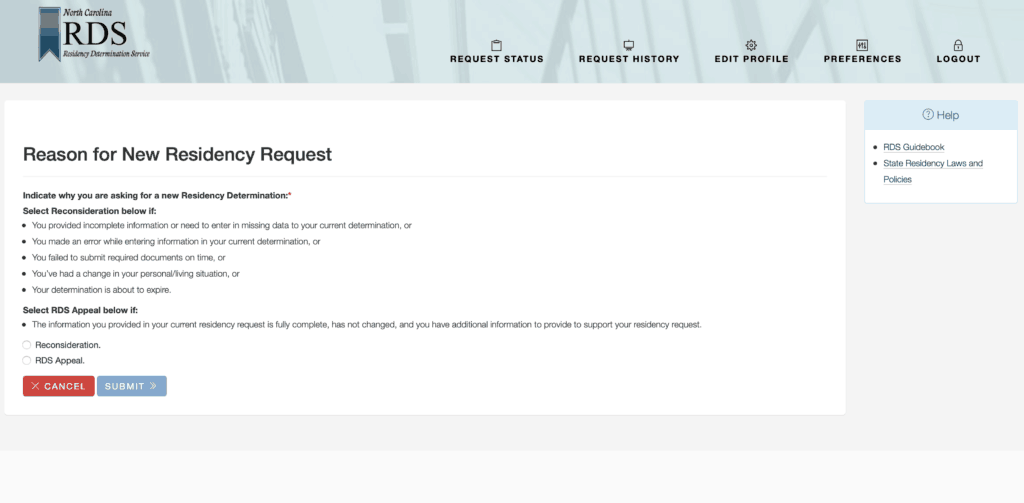

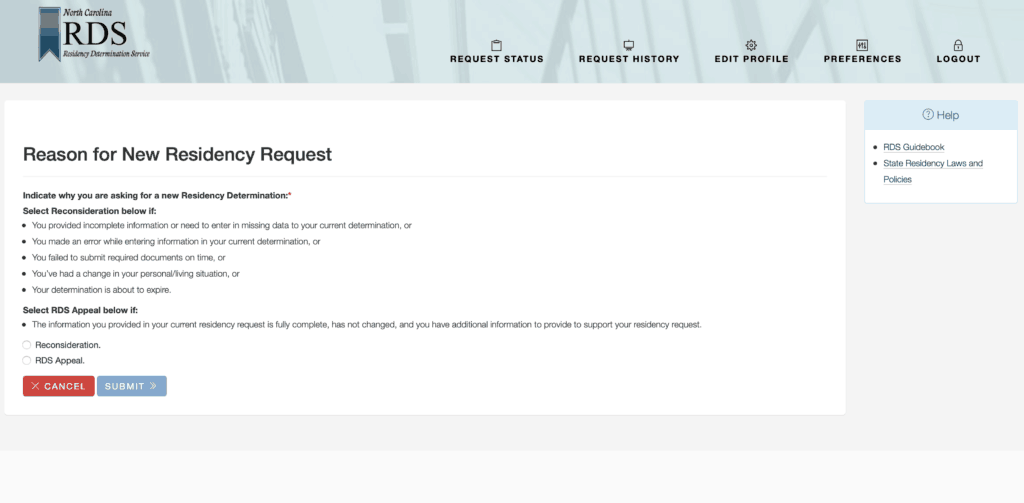

Applicants can request either a “reconsideration” or a “RDS Appeal.” At that point, the student is given a closer look and examined for other potential outcomes. While this process will not allow for a determination that is contrary to the law, it will look for other circumstances that would call for in-state status within the law.

For instance, the state laws include various options for students who might not otherwise qualify as in-state, such as a five-year rule that states that a minor who has been living as a minor in North Carolina for five years is a resident. Through the reconsideration process, RDS would ask the student questions to explore that possibility. It would look at other situations, as well, such as homelessness.

“If the student goes through the questions and RDS says that they are not a resident, then they have the opportunity to say ‘I’d like you to reconsider, I have additional information to tell you about,’ and they can present that information, and they can appeal as well,” McDuffie said.

“Through both of those processes, sometimes we don’t even need to talk to the student,” she continued. “They can give us enough information on the computer. And somebody is eyeballing it but then we can move forward and verify through the other sources that we’re linking to and” — as if checking a list — “say, yep, yep, yep, this is going to be okay.”

Initiating either a reconsideration or appeal is as simple as clicking a button to do so. In an era where chat bots and Amazon are replacing toll-free customer service and brick-and-mortar shopping experiences, the ability to run the process entirely online is attractive to some.

But community colleges worry that, while that may be true of some of their applicants, some are in rural communities that have inadequate access to internet and others need personal contact to ask questions and be given encouragement to get through the process.

RDS does not want to discourage these students. It presents options for scheduling a telephone or in-person meeting through the RDS appeals process, as well as providing a customer service number for applicants to call at anytime during the process.

“We do not want this to be a barrier,” McDuffie said. “We want them to call, we want them to present themselves. We’re doing a lot of reaching out and doing a lot of training with the influencers and the support systems [for these students] — for younger students, anyway, but it’s hard to get at the older students.”

For the community colleges, which worry that their students won’t move on to the reconsideration or appeals in high numbers, the process remains a source of concern. But RDS officials say that the two-step process is the best way to present the most opportunities for students to get an in-state determination.

This is because most college applicants — at the combined 114 institutions — will not need to go through the same inquiries, such as for the five-year rule or other non-traditional circumstances. So it’s better to simplify the initial determination interview and reserve unique cases for the next step in the process.

“We just couldn’t capture it well,” McDuffie said of building the myriad exceptions into the initial interview. “So that’s when we really started presenting [future interview] options.”

There was another reason to reserve some question for reconsideration or appeal, as well. You may have read about David, a U.S. citizen whose parents are undocumented, in Part Two of our series. RDS is specifically designed not to ask whether a parent is here legally. Those situations are intentionally handled by RDS to encourage live communication between RDS and the applicant.

RDS officials say they designed it to get the information they need, but not collect more than that “because we can’t guarantee that ICE won’t show up, or whoever, and subpoena information if we have it. … We wanted to be sensitive to sensitive situations.”

No solution was going to be perfect — the previous method of determination was not and officials acknowledge that RDS isn’t perfect today.

“But we listen,” Canady said. “The most important thing is that we listen.”

There have been more than 32 RDS releases these past two years. Most new releases were motivated by improving the applicant’s experience — such as by removing questions no longer needed as a result of improved electronic validation, or modifying language for clarity and providing additional online support designed to make the student’s experience more helpful.

Many of these modifications were based on input from various influencers and support groups – like student focus groups, high school counselors, campus representatives and others working in partnership with RDS to enhance the student’s experience. RDS officials say they want to understand issues and concerns, and they want to make RDS as effective as possible.

The UNC System schools, for instance, did not want to require their students to go through a residency determination before applying to their schools. They wanted applicants to be able to forego residency determination altogether (if they were willing to be considered out-of-state) or complete the process later.

“There was very strong feelings about that,” Canady recalls. “We listened and sat down and reached a compromise that there would be initial, uniform language on the admission applications and that a person could clearly check whether they wanted to be considered or whether they did not want to be considered for in-state.”

If they checked that they did not want to be considered for in-state residency, then RDS and SEAA would have no responsibility for that. Instead, it would fall back on the universities.

Canady said she and her HECAC colleagues have welcomed similar conversations with the community colleges. In fact, there have already been several brainstorming sessions with community college representatives on HECAC. The limitations on dependency presumptions for married and older students were borne from those talks.

McDuffie and Canady say they recognize that demographics of students seeking higher education are changing, so RDS officials continue to meet monthly with stakeholders, perform data analysis to identify any common roadblocks and solicit feedback from a wide audience. In doing so, they continue to search for ways to improve.

“RDS is not perfect — no system is,” Canady said. “We know that. But we have been very responsive and we continue to be. We want to be sure that every student can get through it.”

Part Four of this series, released tomorrow, will cover a legislative proposal the community college system is exploring to remove road blocks for their prospective students.