Share this story

- A new book showcases findings from their 17-year long study on the impacts of the early college model. Here are some key takeaways.

- North Carolina is a national leader in the early college model, as affirmed by research in the new book "Early Colleges as a Model for Schooling: Creating New Pathways for Access to Higher Education." Here's what you need to know.

|

|

Julie A. Edmunds, Fatih Unlu, Elizabeth J. Glennie, and Nina Arshavsky, co-authors of “Early Colleges as a Model for Schooling: Creating New Pathways for Access to Higher Education,” have been studying the effects of the early college model in North Carolina for the past 17 years. Their new book highlights the strengths and challenges of early colleges and makes the argument for expansion of the model.

EdNC spoke with Edmunds, Glennie, and Arshavsky about their research, the benefits of the early college model, and the path forward for the model in North Carolina. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

EdNC: What are early colleges? How do they differ from traditional high schools in North Carolina, both instructionally and culturally?

Edmunds: North Carolina has legislatively authorized schools called Cooperative Innovative High Schools, or CIHS, and around the country, those schools are generally called early colleges. Per North Carolina’s legislation, these have to be small schools focused on students who are underserved and underrepresented in college, particularly first-generation students and students at risk of dropping out of high school.

The defining characteristic of early colleges is a strong emphasis on college. These schools merge the high school and college experience so that students have the opportunity to graduate with a high school diploma and two years of college credit or an associate degree.

Under Career and College Promise, North Carolina offers dual enrollment opportunities for students in regular high schools, but early colleges are different because the intent is to try to get as many kids as possible to actually receive an associate degree.

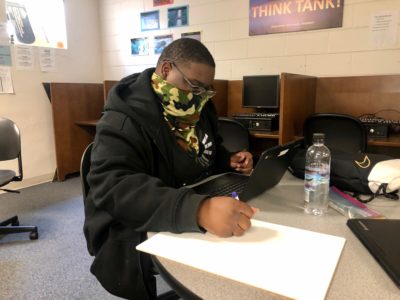

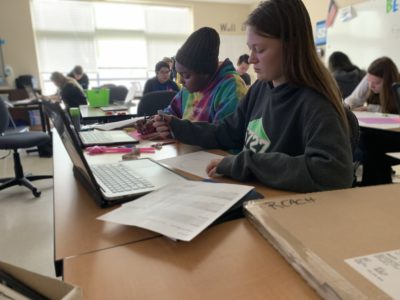

Early colleges make sure that the high school courses that students are taking are the ones that are going to get them ready for college and that the instruction of those courses is student-centered and rigorous. Early colleges also pay much more explicit attention to skills necessary for college, like time management, note-taking, study skills, and self advocacy.

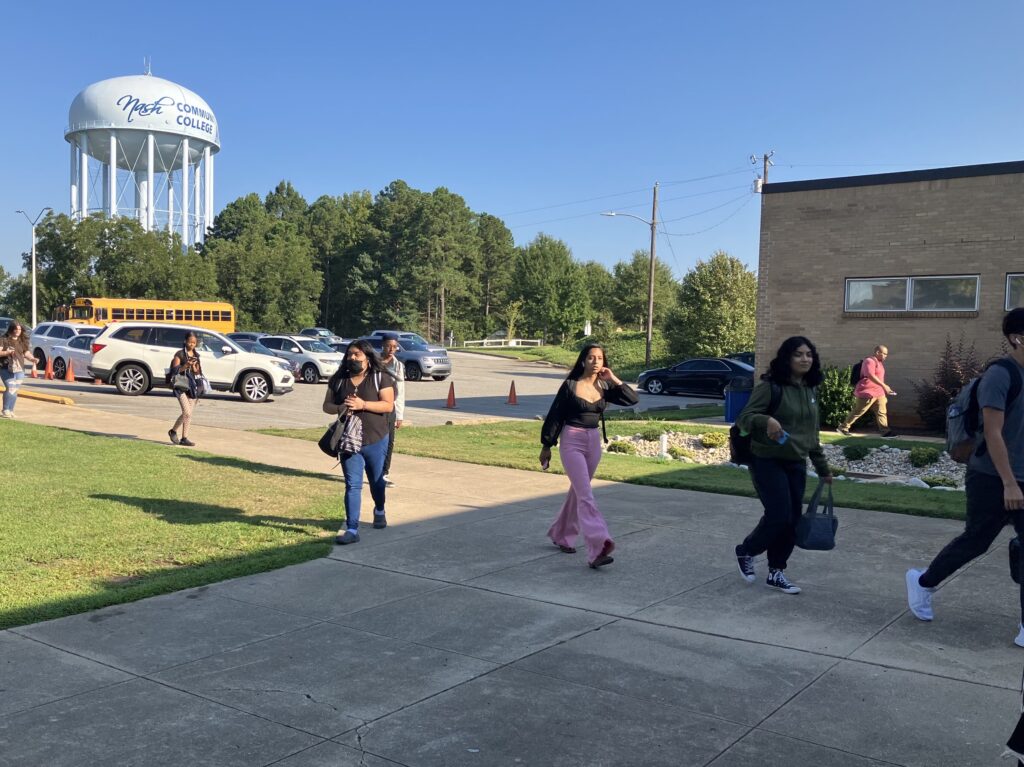

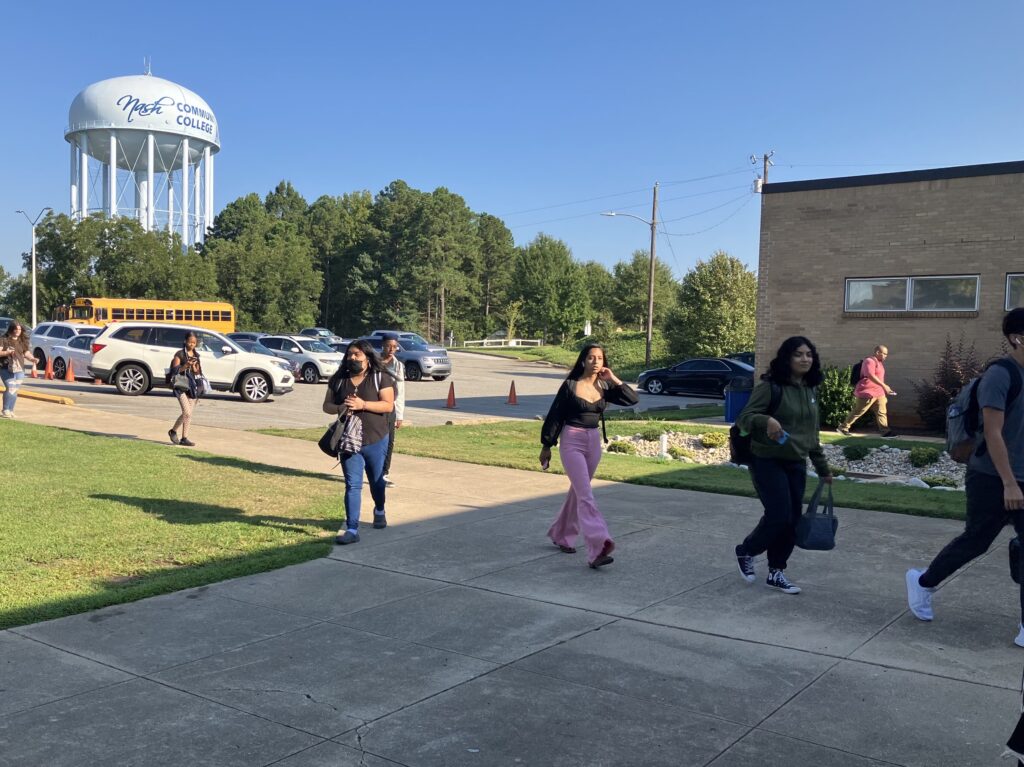

Glennie: In North Carolina, most early colleges are located on college campuses, typically two-year campuses but also some on four-year campuses.

Imagine a first-generation college-goer, who may never have set foot on a college campus and really has no understanding of what life would be like in college, but as an early college student they get to be on the campus and they can use campus resources and interact with college students. It really opens up their eyes and thoughts to the possibility of college, which is one important cultural component of North Carolina’s system.

Elizabeth Glennie

EdNC: Tell me about your research. How do outcomes for early college students differ from traditional students?

Edmunds: We’ve been doing an experimental study for the past 17 years. The study involves early colleges that were oversubscribed, meaning there was more interest from students than the schools could accommodate.

Schools that worked with us had agreed to use a lottery to select students for admission. All the eligible applicants were randomly sorted into students who got in and students who didn’t get in, and then we compared the outcomes for those students.

Our study found that at the high school level, early college students were less likely to be suspended, they were absent fewer days, and they reported better student-teacher relationships. These students earned more college credits while in high school, were slightly more likely to graduate from high school, and were much more likely to enroll in higher education. They were about three times as likely to get an associate degree than students in our control group, and they were more likely to get a bachelor’s degree, particularly those who were first-generation students.

The only negative impact was on English self-efficacy, meaning they didn’t feel as competent in their English skills. We think that that was because the expectations of them were higher.

Glennie: When we give students the opportunities and the support through the early college model, they succeed. Students in the control group that didn’t have the opportunities, they probably could have done it too if they’d had the option coupled with the support and encouragement that early colleges provide.

EdNC: In your book, you reference the misalignment between high school and postsecondary institutions. Tell me a bit about that and its effects on the postsecondary experience for students. How does the early college model address that gap?

Glennie: High school and college systematically developed differently, and they operate separately. The expectations of high schools and of colleges are different, which creates an academic gap between the two, leaving students unprepared when they enter college. By immersing high school students in the college experience through college courses on a college campus, the early college program helps students bridge those gaps.

Arshavsky: The different expectations between high school and college stem from the fact that high school is mandatory and college is optional. In high school, it is the school’s responsibility for the students to graduate, because it’s mandatory, but in college, it’s the student’s own responsibility to graduate and succeed, because it’s optional. It’s up to the student because they are considered an adult while in college but not while in high school.

Edmunds: In the book, we really are making the case that there’s multiple barriers to college enrollment that come from this misalignment between high school and college. The policy solutions for addressing those barriers have tended to focus on individual barriers, but each solution is isolated and it doesn’t make the other barriers go away.

The early college model is a much more comprehensive approach that addresses all of those barriers at once.

Julie Edmunds

Students are getting the courses for free, they have a lot of support to apply to college, and the early colleges are making sure that their high school courses align with college courses. The early college model is truly about addressing this misalignment by combining the two systems.

EdNC: Tell me about some of the other prominent barriers to postsecondary degree completion and how the early college model addresses these barriers.

Edmunds: We talked about four sets of barriers in the book. The first of these are the academic barriers, caused by high schools not sufficiently preparing students for the rigor of college. Early colleges address this by making sure that students are taking the courses that they need, and that the instruction provided is rigorous and aligned to the expectations of college.

Then we talked about cultural misalignment, which involves differences in behavioral expectations, and the early college helps them with that. They are scaffolding students so that they can eventually work their way to independence before college.

Then regarding the financial barrier, students don’t have to pay for their college credits while they’re in the early college, so they can get an associate degree for free and they have the opportunity to significantly shorten their time in college and save money doing so.

And then there are logistical barriers, which include getting students to fill out their college and financial aid applications, and there are a lot of supports that are embedded in the early colleges to help them through those steps to remove those barriers to college admission.

EdNC: Your book follows the compelling success stories of three early college students. What made them choose the early college model, and what are some of the reasons other students noted for their choice?

Edmunds: It was actually a range of reasons. One of our three students was a young Black woman who had been in gifted programs when she was younger, but she was the only Black student in those courses. She chose to attend an early college that was housed on the campus of one of North Carolina’s historically Black colleges and universities because she wanted to be with other kids who look like her and wanted to have rigorous class experiences.

Another one of the students was from a low-income family and was Latina, and for her it was important to be able to get some of her college credits for free.

Then, we had a young man whose parents made him apply, even though he wasn’t really interested. But the experience positively shifted his expectations and his perception of himself. In other interviews, students mentioned not wanting to go to regular high school because of the size and fear of fitting in and preferring a smaller environment.

Arshavsky: Very often we heard that students were the misfits of their school because they were more interested in learning and in academics. Students at early colleges share that interest and academic focus.

At the early college, students felt like part of a family, which was very different from the traditional high school experience and contributed to their choice to attend the early college instead.

Nina Arshavsky

EdNC: Can you speak to how the early college model serves those traditionally underrepresented in higher education and works toward closing equity gaps in education?

Glennie: One reason is by having the same expectations of all students and giving them all the same support to help them succeed. Early colleges also try to recruit students in lower socioeconomic groups that are less likely to go to college. So they are serving students that have a greater need.

Arshavsky: We heard from both teachers and students that those who are underrepresented are capable of the early college workload, but they don’t have expectations for themselves that they will be able to succeed in college. By setting a goal for them to complete college courses successfully, the early college changes their expectations and shows them that they can succeed and really changes their perception of what they can do.

Edmunds: If you look at the statistics for dual enrollment participation across the country, it’s predominantly white female students and more advantaged students who are participating. Early colleges are pretty much the opposite of that. They are generally representative of the district on characteristics like race and ethnicity due to that intentional outreach and targeting that they do, which is not the case in regular dual enrollment programs. It is an explicit and purposeful focus for the early colleges to serve these students.

EdNC: What makes North Carolina’s early college model one of the leading models in the country?

Edmunds: In the beginning, the nonprofit organization called the New Schools Project was instrumental in identifying a set of design principles that North Carolina’s early colleges would follow. It laid out how a school needed to look in order to support students in taking college courses and in trying to get an associate degree or two years of college credit. There was a clear articulation of the model and then there was ongoing support for schools as well.

In North Carolina, schools have to meet certain standards in order to qualify as an early college and receive additional financial support from the state.

North Carolina has a comprehensive vision of how the early college high school should be implemented, which creates a positive experience for students and contributes to a broad-based commitment to the model within the community.

Julie Edmunds

Glennie: It is not just individuals making up their approach to early colleges. These are researched approaches that have strengthened the model across the board.

EdNC: You speak of three early college expansion models. Can you tell me about those models?

Edmunds: One of the challenges with the way the early college model is implemented in North Carolina is that these are small schools on college campuses, so while they create a really great setting, they’re limited in terms of their capacity. Some students don’t want that small school experience on the college campus, some of them want that big high school experience. So in thinking about how to expand this model to serve these students, we see three main ways to do so.

One way is to create more small schools. Every district can have at least one if not multiple early colleges, but you’re still going to be limited in terms of the number of students that are served.

Another option is to create an early college academy within a larger high school that students can participate in.

Lastly, Texas has some good models of where the entire comprehensive high school is an early college and the expectation is that all students will get some college credit but not all students are going to get an associate degree. These schools are starting to implement more technical credentials, such as HVAC and other certifications. By making sure that the college courses that these schools offer appeal to a wider range of students, the schools will be able to expand the reach of the early college model.

EdNC: What are some common challenges to expansion?

Edmunds: A common challenge is the capacity of colleges to support this work and to offer these college courses. Rural and urban schools will face different challenges. Rural schools may not have a postsecondary partner that’s geographically close to them. North Carolina is in a better position because we have a really robust community college system that is nicely spread out, which is not the case in other states with rural communities.

There’s also a lot of logistics for these partnerships to navigate. It’s not easy. But, obviously, we think it’s worth it.

Arshavsky: There are states that will not pay for more than 18 college credits per student. So states are very different regarding their financial commitment to this model, which poses a challenge.

EdNC: Looking at North Carolina specifically, what do you see as the path forward for the state’s early colleges?

Edmunds: In North Carolina, there’s certainly room for continued expansion. There are many schools that are still oversubscribed, which suggests that there’s much more interest than these schools can accommodate.

There are a few districts that don’t have early colleges where I think the population could certainly benefit from them. So I would hope that we’ll continue to see some additional small early colleges being implemented.

The other hope is that we can take the lessons learned from early colleges in the state and apply them to the Career and College Promise pathways to be more intentional about outreach, expanding access, and providing support.

I also hope that we start thinking holistically about the education system as well. The early college model proves that we can merge the high school and college systems and it can be good for students. If legislators can think more holistically about these systems, that can help us make better decisions about models of schooling that are beneficial for our state’s students.

Glennie: I think many educational leaders in North Carolina know that we have a good thing going here with the state’s early colleges. We don’t have to persuade them. There is openness to trying out new things and for educators to be empowered to try new approaches in traditional high schools to see what works best for students.