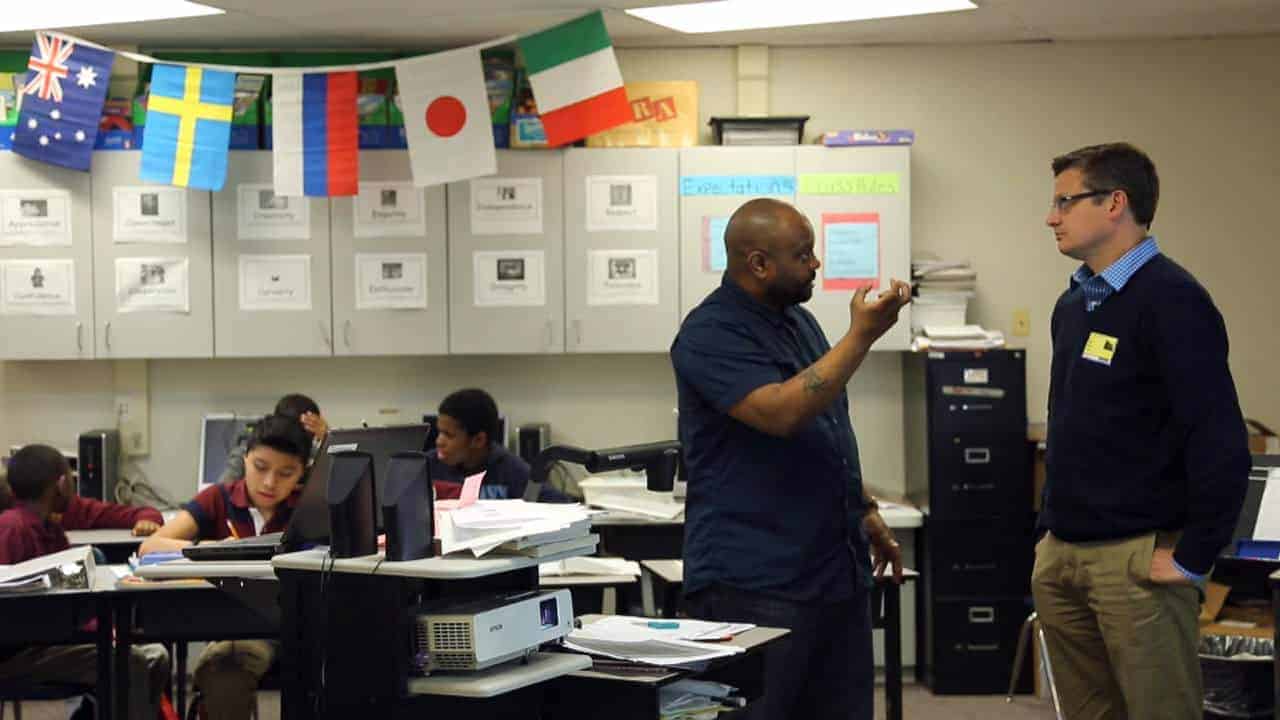

Across North Carolina, teachers are asking tough questions. But this isn’t a pop quiz for students. Teachers are challenging themselves — in collaboration with instructional coaches — to answer incisive questions about their role in student learning.

Job-embedded instructional coaching is a form of professional learning provided to teachers to stimulate the self-reflection and self-analysis needed to improve or refine their instructional effectiveness. 1 Coaches partner with teachers to examine the connections between their instructional planning and classroom culture, and what students are asked to do and what they actually do. While just 19 percent of teachers implemented a new practice in their classroom after attending a workshop that included modeling, practice, and feedback, 95 percent of teachers did so when coaching was added. 2

A team of expert instructional coaches from our organization, RTI International, is supporting this development in schools across North Carolina. Founded in 1958, RTI is a nonprofit research institute headquartered in Research Triangle Park. Our school services team supports teachers and leaders with coaching, consulting, and peer learning opportunities. A Duplin ECHS teacher explains how her RTI coach helped her: “[My coach] helped me significantly improve my lessons by helping me reflect, brainstorm, and come up with strategies that I hadn’t tried before. [She] helped me increase my use of technology in the classroom and solved several tech issues I was having. [She] put things in perspective and helped me find ways to streamline my work and be more efficient.”

Instructional coaching differs from other common forms of professional learning because teachers identify both what they want to improve upon and how they’ll go about improving. Coaches facilitate this reflection and planning, asking probing questions as a way to deepen teachers’ thinking. As in other professions — think athletes or singers — coaches provide another set of eyes and perspective to teachers and help them further develop their “professional capital” — the knowledge, relationships, and decision-making resources from which teachers draw upon as they work to meet the needs of all students. 3

In this way, instructional coaching recognizes and utilizes teachers’ professional expertise and knowledge of their classroom context. This respect for teachers as professionals is increasingly important as teacher turnover rates continue to climb while the student population and diversity increase. 4 Retaining experienced teachers who may be feeling burnt out or underappreciated is especially critical in North Carolina, where the decline in undergraduate enrollment in teacher education programs outpaces the national trend. 5

As a large, nonprofit research institute, RTI may seem like a surprising home for a team of education practitioners, but this relatively new arrangement has benefits for both schools and researchers. School-based educators gain opportunities to work with researchers, access to high-quality and relevant research findings, and resources to conduct action research in their own classrooms. These educators in turn contribute to the researchers’ knowledge base on current educational practices and practitioner voice. With much of RTI’s education research centered on large, national surveys of students and teachers, the instructional coaching team provides an important bridge to understanding the work North Carolina educators engage in everyday to reach their goals and the challenges they must overcome to do so.

While instructional coaching can take many forms, RTI uses a cognitive coaching model designed to build the instructional capacity of teachers. Within this model, coaches partner with teachers in cycles of observation and feedback through structured reflection on their practice. Teachers build the mental models and decision-making skills necessary to make instructional choices that are beneficial and equitable for all students. 6 This is in comparison to what occurs in more traditional models, where cookbook solutions are dished out in response to a topical issue without consideration for the classroom context. RTI’s coaches ask teachers to reflect upon their instructional decisions so that teachers themselves identify and articulate the links between their actions and student learning.

RTI’s educational practitioners seek to recast coaching as a resource that all teachers can benefit from, no matter their level of experience or expertise. As Atul Gawande7 shares in his New Yorker piece, “Personal Best,” few people can reach and maintain their peak performance on their own. Yet modern schools have been described as egg crates, with classroom walls isolating teachers from their peers and hiding instructional practice from public view. 8 This separation can make it difficult for teachers to observe and learn from one another. Coaching offers a way around these structural barriers by providing teachers with a mirror-like reflection on their professional practice, allowing even highly experienced teachers a means to improve.