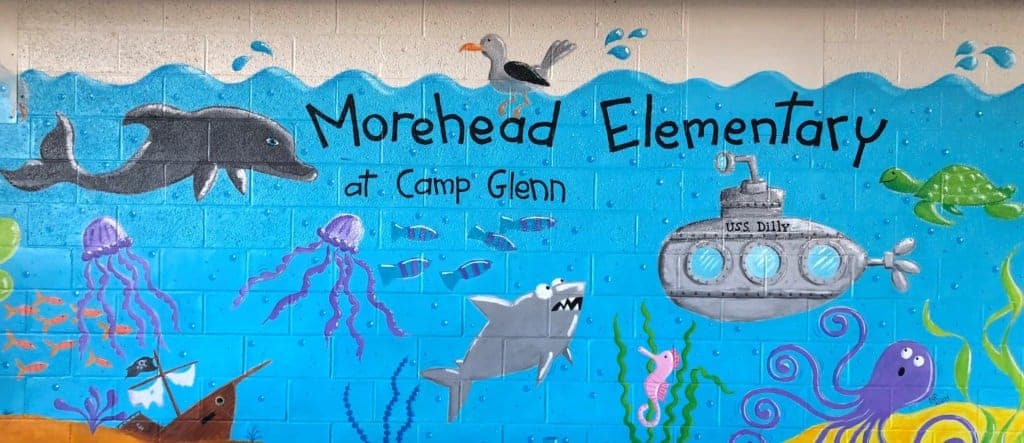

Ignite and inspire were the first words we saw painted on the walls when we walked into Morehead City Elementary at Camp Glenn in the Carteret County Public Schools on our Crystal Coast.

It was a powerful reminder that all of the public policy issues we have been thinking and writing about at EducationNC — from the need for special electives to class size, from infrastructure to 1:1 learning environments, from the need for the best teachers and principals, to funding and governance — play out in classrooms and schools across our state that are designed to ignite learning and inspire students.

During national Public Schools Week, EdNC’s founders and the chair and vice chair of our board of directors respectively, Gerry Hancock and Ferrel Guillory, honored public school students, teachers, principals, and schools by continuing to learn about the challenges and opportunities facing public education in the 21st century.

Public school kids make great principals

Adam Olander is the principal of Morehead City Elementary. Olander was a public school kid before he was a public school teacher and now public school administrator. He grew up in Boone and attended Green Valley Elementary for K-8 and then Watauga High School. He studied economics and information systems at UNC-Chapel Hill — “Go Heels,” he says, when we sit down with him — and then eventually he became a math teacher at West Carteret High School. That was 15 years ago. He went on to attend UNC-Wilmington’s Principal Fellows Program, working as an assistant principal at Queens Creek Elementary, Smyrna Elementary, Havelock High School, and then West Carteret High School before landing at “Camp Glenn” two years ago.

The property where Morehead City Elementary School is located has a rich history dating back to the Civil War, and locally folks still refer to the school as “Camp Glenn.” Olander says of the school’s place within the community, “this school goes way back.”

The principal shares this story about the school’s name, told by a local, a grandmother of a student:

“This school was called Camp Glenn Elementary from its inception. There was also a Morehead City Elementary in downtown Morehead City. When the new primary and middle schools were built, the old Morehead City Elementary in downtown was abandoned and that entire staff came to Camp Glenn Elementary. Because of this, Camp Glenn Elementary was changed to Morehead City Elementary. This went on for awhile until a Board of Education member pushed to have the name changed to its current name, which is Morehead City Elementary at Camp Glenn.”

Currently the school is a 4th/5th grade center serving 300 students. As the student population has grown in the county, creating this center allowed for better use of existing infrastructure. Olander notes, too, “it is a way for students to leave primary school behind and start making the transition to middle school.”

The school shares the property, parking lots, gyms, and cafeteria with the local Boys and Girls Club.

At Camp Glenn, there are 130 fourth grade students in six homerooms, and 170 fifth grade students in eight homerooms. But special electives — art, physical education, computer lab, music, STEM, and the media center — plus interventions for reading, math, and exceptional children give students the opportunity to rotate through classroom spaces and teachers.

These are not “sit and get” classrooms

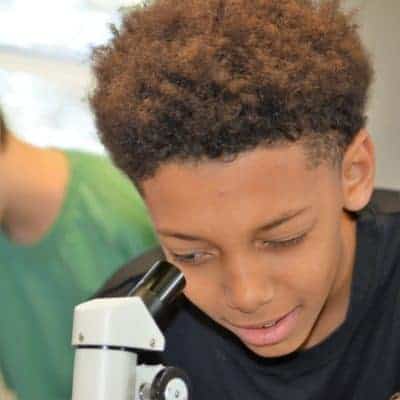

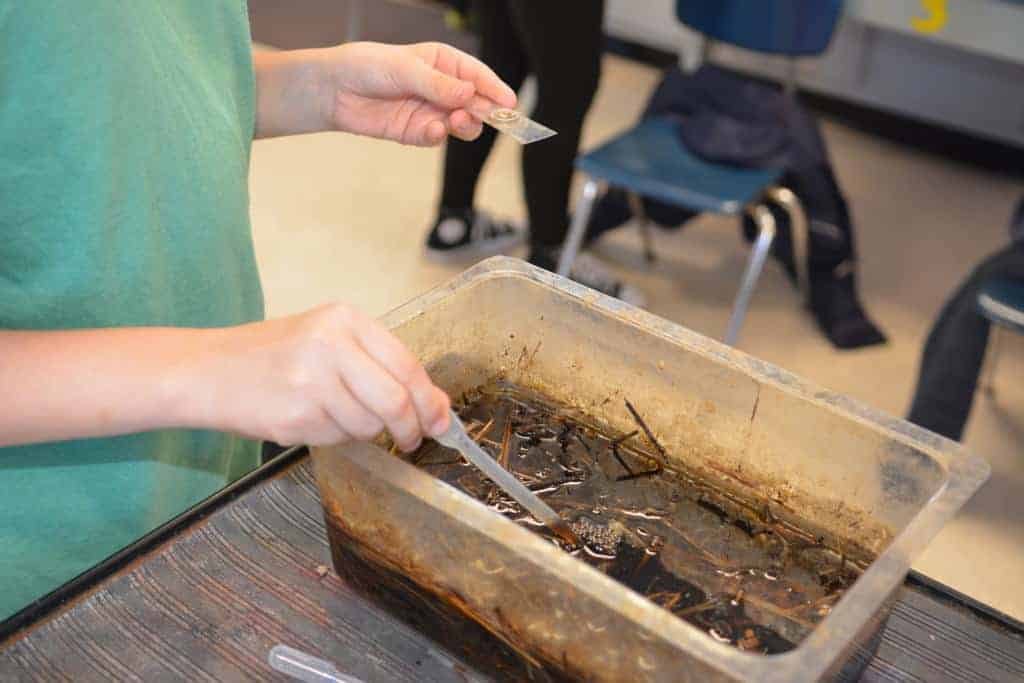

In this science laboratory, each student has access to a microscope, and they are beginning to learn about the human body by learning first about plant cells, animal cells, and unicellular animals. Owen calls me over asking, “Do you want to see how gross it is?”

The science laboratories are taught by “the teacher of record” with assistance from a beloved science instructor, Al Johnston, who showed up 16 years ago passionate about science and wanting to volunteer with students to share his knowledge. Olander says somewhere along the way “there was a movement to compensate Mr. Johnston.”

You can tell a lot about a principal by watching him in a classroom. You can tell if it is unusual for him to be there by the way the students and teachers react. You can tell whether they are hands-on or hands-off by whether and how they interact. Olander was the first one to respond when a student accidentally broke a glass slide for the microscope, kneeling down to make sure he picked up all the shards.

Instead there is a “wow” factor

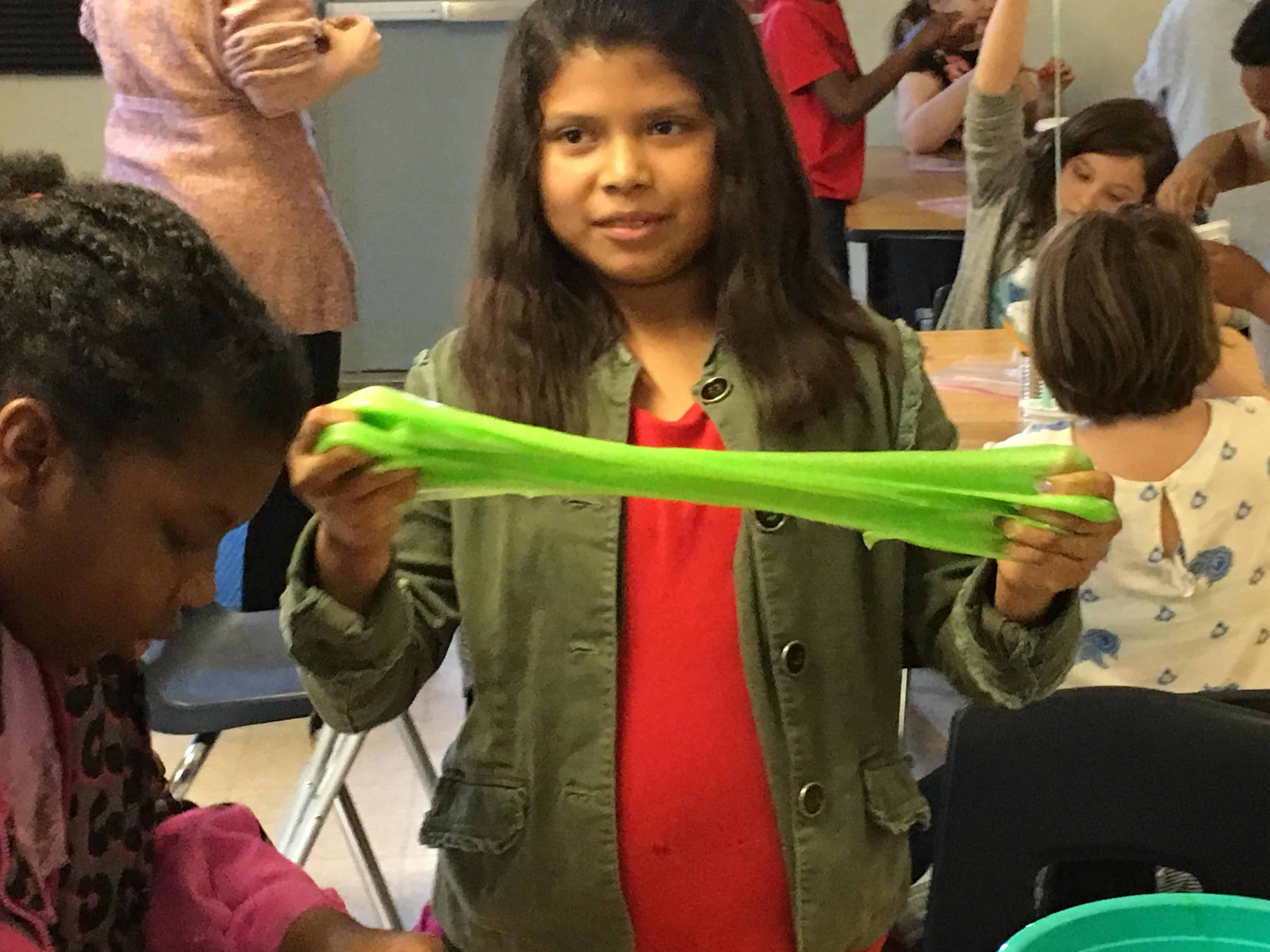

In this STEM classroom, Rebeccah Haines teaches students chemistry and team work by making slime with shaving cream, glue, colored dye, and liquid starch, which serves as an activator. Housed in what they call the “WOW” building, this instructional space used to be an old outbuilding.

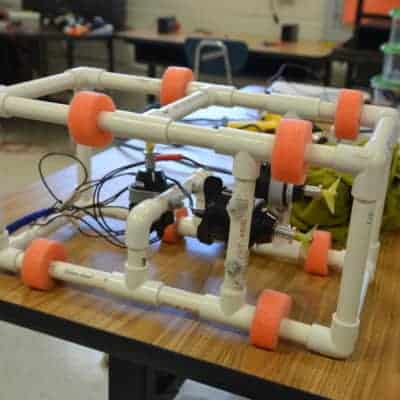

All fifth-graders at the school are exposed to underwater robotics, and there is a pool to test the robots. The robots are built and programmed to perform specific tasks, like picking up rings from the bottom of the pool floor.

During our visit, Carteret County’s mobile dental lab is delivered to the school via truck, and it will stay at the school for about three weeks so the students have access to dental care.

Design thinking allows students to create knowledge vs. consume knowledge

Two years into his leadership, Olander is proud that Camp Glenn is a “C” school — and just two points from being a “B.” He notes that the school was 5/100ths from making growth. “If you concentrate on growth, proficiency will come,” he says. Fifty-four percent of the students qualify for free and reduced price lunch.

When we ask about the challenges facing public schools, Olander says what we hear so often, “We’ve got to get the best people we can in the classroom.” He worries the teaching profession is becoming less “feasible,” noting the rising cost of health care and understanding that his teachers need to be able to raise a family, pay the bills, save for retirement. He worries about the loss of funds that used to compensate teachers for staying after school to remediate students and cover the costs of the national board certification. All of these things add up, and over time he worries it makes it harder to attract teachers, especially in areas where the Crystal Coast does not beckon.

“I feel blessed,” Olander says. He notes a supportive school board and parent base as well as access to instructional supplies.

Once we make our way into the classrooms with the students and the teachers, it is clear Olander’s leadership ignites and inspires. Design thinking principles are in the DNA of the classrooms, the school, and the leadership.

What if we used design thinking to collectively think about the kind of classrooms and educational experience we want for all of our students now and in the future? Ask. Imagine. Plan. Create. Test. Improve.

This week we celebrate all that our public schools are and all they will become.