EdNC is highlighting the experiences of educators, families, researchers, and advocates with a stake in North Carolina’s early care and learning landscape. These profiles illustrate that care and education are inseparable, especially in a child’s first five years — caregivers educate, and educators care. In this series, we refer to those profiled in the way they are known by their community.

Davina Boldin-Woods, executive director of First Presbyterian Child Development Center in Burlington, has six remodeled classrooms that are stocked with crisp new cribs that have never held a napping infant, shiny new books that have never been opened by tiny hands, and cuddly new toys that have never been hugged by eager little arms.

“The materials are ready, they’re here,” Mrs. Woods told EdNC during a tour of the classrooms. “It’s a waiting game.”

What she’s waiting for is teachers.

Like many center directors across North Carolina, Mrs. Woods is facing a staffing shortage that she attributes to low wages — infant and toddler teachers typically earn less than $14 per hour in our state.

That has left her center with six empty classrooms and a waitlist of 144 infants and toddlers.

“I would take every single child that I could if I had the space and the capacity,” Mrs. Woods said.

Not a sense of ‘if you build it, they’ll come’

First Presbyterian Church in Burlington had been providing early care and learning for almost 50 years when Mrs. Woods joined the team in 2022. She immediately saw an opportunity to expand their capacity.

“I passionately went before First Presbyterian Church and said, ‘Listen, you guys have this wonderful facility. You have an abundance of space that is not being optimally utilized. We have a waitlist of 200 families.’ And they graciously said yes,” Mrs. Woods said.

The Cannon Foundation provided more than $200,000 in grants for various outreach programs at the church, much of which went to converting underutilized spaces into classrooms that meet the state’s strict licensing requirements for infants and toddlers. The center also received a $25,000 grant from Impact Alamance to furnish the rooms with developmentally appropriate materials and supplies.

The result was seven new classrooms — but only enough staff for one.

“It was not a sense of ‘if you build it, they’ll come,’” Mrs. Woods said. “At one point in time we had the staff. We had made a very concerted effort to onboard for this.”

She spent almost two years creating “top heavy” teams of educators to teach in her existing classrooms while the new ones were under construction. This meant she had more teachers than the center’s five-star license required. Her plan was to build teaching capacity during construction, then move teachers into classrooms as they opened up, and whittle down that student waitlist.

“But by the time we got there, all of our people kind of faded away,” Mrs. Woods said. “My teachers started retiring. We had someone get sick. We had some that decided to go to other professions, and so the plan that we had in place to staff the classrooms dwindled.”

‘We need sustainable funding’

First Presbyterian Child Development Center doesn’t have a history of the turnover challenges that many other centers face. Mrs. Woods said there are staff members who’ve taught there for two or three decades.

With more than 30 years of experience in child care herself, Mrs. Woods describes her current role as an advocate and change agent in the field.

“It’s always been my mantra that if I take very good care of the women who take care of our students, they’ll take very good care of our students,” Mrs. Woods said.

“We wrap them in the things that they need to be great women and great mothers and great wives, so that when they cross the [classroom] threshold, they can be great educators. And that works until it doesn’t, because it still doesn’t impact their paycheck.”

One option for increasing teacher wages at the center would be raising tuition. Of the center’s 92 students between the ages of 6 weeks and 6 years, about 10% use state subsidies to help pay tuition.

“We need sustainable funding, because parents can’t afford the actual cost of care,” Mrs. Woods said. “And all of this should not be held on the shoulders of our families anyway.”

She pointed to a number of programs that could be expanded to support livable wages for teachers — which helps maintain affordable tuition for families.

Child Care WAGE$ Program

Mrs. Woods worked for American Express when she dropped off the first of her two children at a child care center more than 30 years ago.

“I went back to the car and cried, and found out very quickly that I was a helicopter mom,” Mrs. Woods said. She pivoted to a career in early childhood education with no early childhood education credentials of her own.

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

She’s grateful for the Child Care WAGE$ Program, which provides education-based salary supplements to early childhood educators working with children from birth to 5 years old.

“WAGE$ kept my lights on,” Mrs. Woods said. It also gave her a path to earning an associate’s degree in early education from Alamance Community College.

The program is active in 67 counties, but policymakers at the second meeting of Gov. Josh Stein’s Task Force on Child Care and Early Education expressed interest in what it would take to get participation in all 100 counties.

TEACH Early Childhood Scholarship Program

Mrs. Woods’ associate degree was the first of four advanced degrees she has earned in the early care and learning field.

The next three were paid for with TEACH scholarships.

“Our historical idea of early education is flawed because people think that we are an uneducated field, and they think that what we do is very easy, and neither are true,” Mrs. Woods said.

She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from NC A&T State University, and another master’s degree from UNC-Greensboro. All three directly relate to her work in early education.

While Mrs. Woods is a beneficiary and fan of TEACH, she pointed out that higher educational attainment doesn’t necessarily lead to family-sustaining wages in the broken marketplace of early care and learning.

As an example, she shared the story of a teacher whose final day was the day of EdNC’s visit. Mrs. Woods said the teacher has three sons under the age of 6, and can’t afford child care for them on the wages she earns teaching and caring for other people’s children — in spite of the fact that she has advanced her own education with TEACH scholarships.

Mrs. Woods said now the teacher earns too much to be eligible for the state’s child care subsidy program, but not enough to cover the actual cost of early care and learning for her sons.

Child care subsidies for child care teachers

Mrs. Woods said she is “apprehensively optimistic” about several bills proposed in the General Assembly this session.

One of those (HB 800) would make child care teachers automatically eligible for tuition subsidies for their own children.

“We know it works, it works in Kentucky,” Mrs. Woods said. And it would help teachers like the one she was losing on the day of EdNC’s visit.

But like other bills under consideration this session, it proposes starting with a pilot.

“There are some things that we just know are right and good and beneficial, and we don’t need a pilot for that,” Mrs. Woods said. “We need to implement those holistically.”

‘It impacts North Carolina’

Mrs. Woods invites policymakers at every level to come visit her classrooms and see the importance of the work up close.

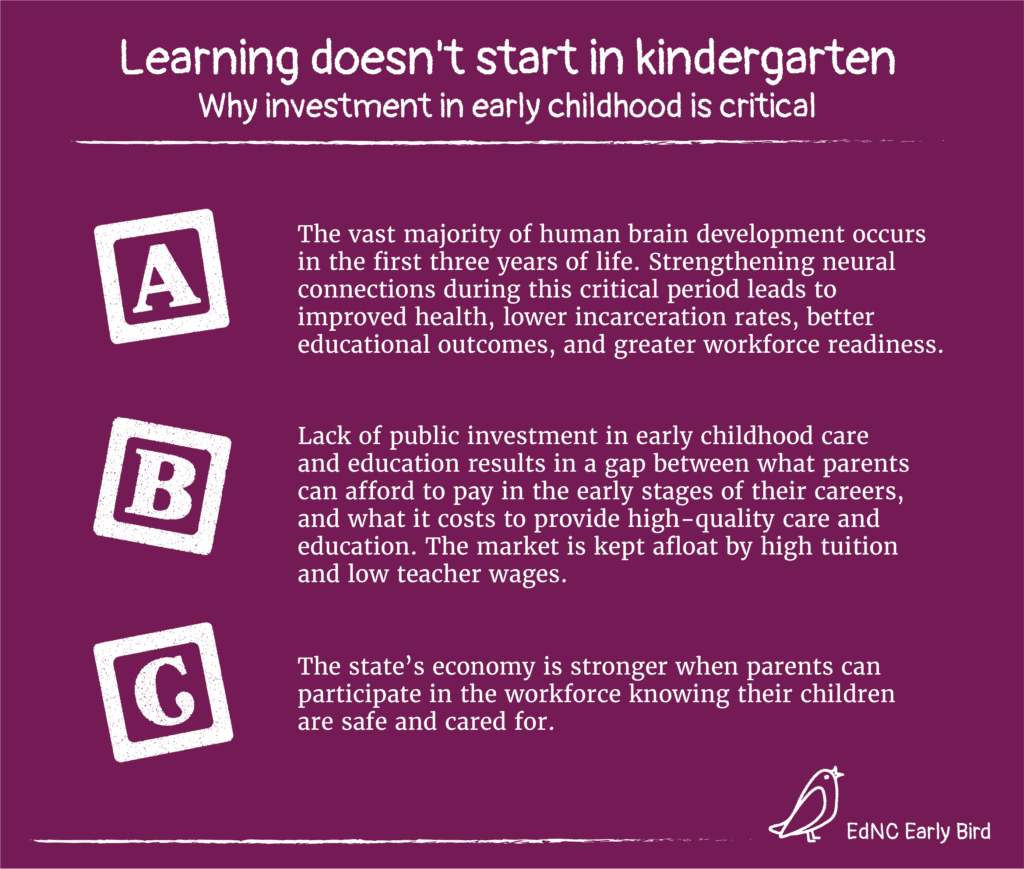

“Brains are not born, they are built,” Mrs. Woods said. “And they are built right here in early education, honey!”

She said the most challenging aspect of working for young learners is convincing others that early care and learning is worthy of investment.

“This is bigger than early education, that if you don’t invest here, you’re going to invest the dollar somewhere, and you’re going to end up spending more,” Mrs. Woods said. “This is not just a parent issue, but this has a trickle-down, domino effect that will absolutely impact our economy; it impacts North Carolina.”

Early care and learning is important for North Carolinians because it’s our future. The things that we are doing now will have the greatest impact on the outcomes that we have in the coming years. The research tells you that the investments that you make in the early years help not only the child, but the economy, and it makes them more productive citizens. They’re healthier overall. They’re more likely to finish school. So all of those boxes are checked just by investing early.

She wants policymakers to know that even though pandemic-era stabilization grants have ended — a fact that keeps her up at night — the early childhood education field has not stabilized.

“There was never a time that it was built on a stable foundation,” Mrs. Woods said. “And so this is going to take a broader approach, some sustainable funding and some support to get this profession that is absolutely essential to the economic impact of North Carolina, to get us to a place where we can be self-sufficient. It’s not that we are asking for a handout. We just need a firm foundation to get us on solid footing.”

Recommended reading