“The place to teach students to ask questions about truth and evidence in our digital age is the history and social studies classroom and we should not delay.” (Wineburg & Martin, 2004).

On January 30, 2018, along with millions of American citizens, I watched the State of the Union address, and the Democratic response to it. One point of divergence was particularly clear between the two speeches: the stance on immigration. In one speech, an anecdote about gang violence that led to the tragic deaths of two young girls was used to justify increased support of border patrol and immigration enforcement. In the other speech, Falls River, MA was selected as the location to deliver the speech (“a proud American city, built by immigrants”). The speaker emphasized the industriousness and resilience of the immigrants who built the city.

As a history teacher, I immediately noticed the difference, and thought about the audiences each speaker wanted to appeal to. I thought about how the speakers carefully selected stories to tell, deliberately deciding against statistics and instead sticking to short anecdotes to communicate the ideas they wanted to share. I wondered what it would be like to be a young person in America; whom would they believe? How would they decide which side of the story resonated, and which side to take? In just a few years, young Americans listening to these speeches will hold the decisive power to vote, and many are already engaging in discussions about politics with their peers online. How are we preparing them to sift through evidence and further, engage in productive discourse about issues that matter?

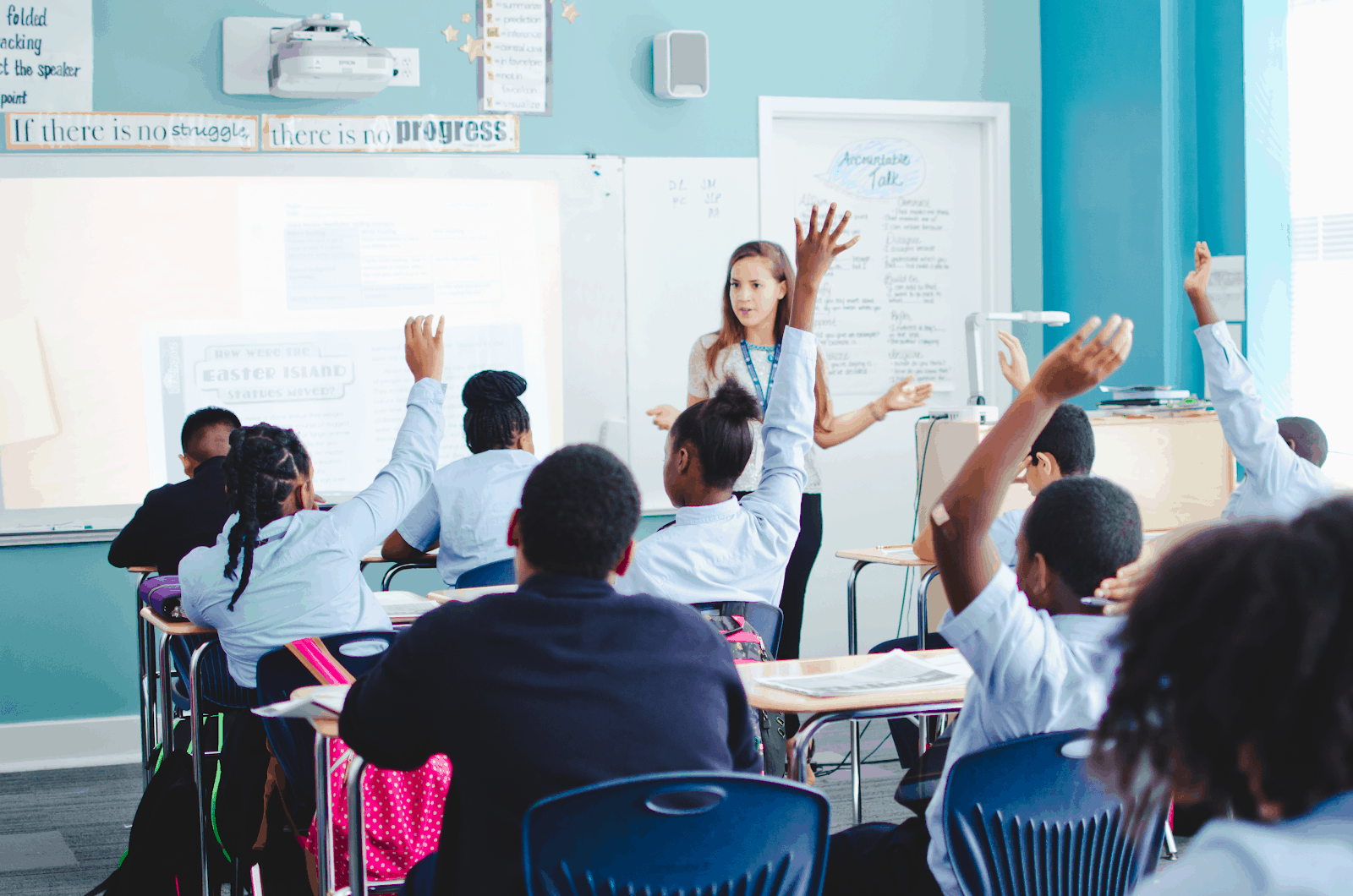

These are the questions I consider in my own classroom, and fortunately, my sixth grade students embrace it. They love to ask questions that challenge the things they read, and often, they raise questions that force me to reconsider my own biases, as well as the strategies I’m using to teach.

Last week, during a lesson where students were confronted with conflicting information, a student asked: if our textbook is biased on this issue and therefore not reliable, why do we still use it?

Here is how I responded: our textbook, like most things we read, is not reliable on its own. It tells stories in the way that humans tell stories—selecting or prioritizing some details over others to convey a message. Textbooks are not the authority on what happened in the past and should not be treated as such—no singular source can accurately explain what happened. Multiple people were involved in creating and experiencing the past, so to tell and learn stories from only one perspective is to shortchange yourself in knowing and understanding what actually happened.

The same can be said for the present: when we choose to focus too heavily on the narrative that one person constructs, we miss out on the opportunity to understand the whole picture and make reasoned judgments about what is happening and what is best for our democracy. Therefore, it is essential that we prepare our students to think critically about what they read and hear so that they are prepared to participate constructively in our government and society.

As I thought through my student’s question, I began to imagine a world where students could hear multiple points of view and work collaboratively to establish truth, or at minimum, mutual understanding. In this world, students would learn to participate in a society where decisions are made through reasoned argumentation, rather than continuous (and often heated) restating of divergent opinions. People would not accept blanket statements made by individuals as absolute truths, but ruminate on the ideas they hear with cautious eyes and ears, understanding that the nuances of human experience, interaction and communication make it nearly impossible for one statement to be entirely objective, and therefore, impossible for one story to tell absolute truth. I imagined a world where instead of listening or subscribing to singular truths, people would choose research, carefully sifting for valid sources and fact check for accuracy and validity.

It sounds idealistic, but with the right steps, we can invest in a nation that trains citizens to participate in a democracy and engage in conversations that ultimately work toward the well being of our nation and its citizens, not just to present and argue over contradicting opinions.

History education: an investment in democracy

With the right investment in history and social studies education, we can take strides to create this world. History and social studies classrooms are the places where students should be diving into complex issues, scrutinizing evidence, developing informed understandings of the world around them, and discussing and debating with their peers. In this way, they can be apprenticed into the work of engaging in a democracy.

What would this investment look like? The North Carolina Essential Standards for 6-8 Grade Social Studies have taken a few steps in the right direction. The middle grades standards include a historical thinking strand, so that students are expected to read and understand a variety of sources, including written documents and alternate forms of data and information, like maps, graphs, charts, and images. In this strand, students are also expected to interpret various historical perspectives related to singular or particular events. Further, the standards have moved away from a focus on teaching pure content to a focus on teaching concepts. In the current standards, teaching the content is implied, but there is also space for students to do complex thinking, and opportunities to grapple with key concepts from multiple perspectives.

Now, the next step is to reflect, refine, and improve to make this form of history and social studies education actionable.

Here are a few ideas to move history education forward in our state:

- Provide history and social studies teachers with adequate resources to teach their content well. The standards were a start, but since then, little to no guidance has been provided to help educators teach the standards well, and materials are often scarce. History and social studies classrooms look different not only district to district, but also school to school and classroom to classroom. Unpacking the standards is hard enough; then, sifting through and finding adequate sources to teach the content in a way that fosters thought and discourse is a strain when teachers are working in isolation and with little guidance. With investment in resources for teachers to use and teach the history standards well, we can focus more on the questions we ask, the ideas we harness, and the debate and discussions we build, rather than the materials and resources we need to teach.

- Create opportunities for professional development aligned to the standards, historical thinking, and assessment. As a middle school instructional coach, the teachers I coach all come from different backgrounds, from the states or districts they’ve taught in, the years they’ve spent in education, and their experiences and personal beliefs about how Social Studies should be taught. One theme seems to recur among new and seasoned teachers alike: many feel they understand the standards enough to teach them well, or they feel the standards were taught differently at their previous schools. With respect to assessment, there is so little guidance given before or during the year about the Final Exam that it is hard to determine how the assessment aligns to the standards, and how to prepare students for it. Professional development opportunities provided at the state level to help teachers derive meaning from the standards and work together to practice and grapple with how to teach civil discussion well would dramatically improve the quality of history education.

- Stop over-valuing multiple-choice assessments. If they are necessary, make sure that other forms of assessment are used as well. Multiple-choice assessments are good for determining quickly what students remember. Content knowledge is important in history education, but more important is what students do with that knowledge. Do they understand how knowledge is acquired and produced? If the ultimate goal is to prepare students for involvement in a democratic society, are they actually better prepared to do that at the end of a course? These are questions that are important to assessing the efficacy of a history education class. They are also questions that cannot be answered through a multiple-choice assessment. If we focus only on what can be assessed easily, we miss the opportunity to teach authentic fact checking and reasoned argumentation.

- Do not judge the importance of a class based on its ability to assess student knowledge in multiple-choice format. In schools across the state, everything from professional development opportunities to performance-based bonuses depends upon whether an educator teaches a tested subject. This impacts morale among teachers of non-tested subjects, and may lead to a certain mindset among teachers and students alike: what we learn in Social Studies, or any other non-tested subject, is not as important as what we learn in English, Science, or Math. It impacts our school’s priorities, and for understandable cause: the numbers pulled from these assessments are used to measure our school’s success. Yet, these assessments are imperfect and can only realistically measure a narrow range of surface-level knowledge. If we think about the purpose of education as a means to develop and prepare each learner for a productive life in our democratic society, then we are doing our students an injustice if we limit the focus of what they learn to what can easily be assessed through a multiple choice test. We should also focus on authentic skills that will move our democracy and our nation forward, like civil discourse.

Educating citizens: a final thought

In her 1930 essay, Good Citizenship: The Purpose of Education, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about cultivating responsible citizens prepared to participate in a democratic society as the ultimate goal of education. According to Roosevelt, the first objective of education is to grow “informed and intelligent citizens,” and the second objective, to “bring about the realization that we are all responsible for the trend of thought and the action of our times.” Almost 90 years later, we are still grappling with the question of how to do this. There is an untapped goldmine of potential in social studies and history classrooms if we are willing to invest in the right resources to teach it well.