Three years ago, Tim DeCresie, Pitt County’s director of digital learning, started taking note of a gap in many students between intellectual capacity and academic performance. He began thinking of ways to bridge it.

“There are kids who have the mind to be gifted but may not have the nurturing or resources,” DeCresie said.

DeCresie’s observation of untapped potential prompted him to start Go Grow (Growing Our Genius by Reaching Our Wonders), an academically gifted (AG) program to develop those students by providing them with avenues of learning of interest to them. STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) is a big part of the program.

DeCresie explained the gap between giftedness and academic performance: Traditionally identified AG students have both achievement and aptitude, he said. The students Go Grow targets have aptitude and characteristics like problem-solving and creativity but lack achievement.

DeCresie said he did not want to lower the standards for who could access the traditional AG curriculum, but instead wanted to provide curriculum that met the specific needs of those children.

It is not yet clear what Go Grow will look like systemwide. But Jeff Butrum, a teacher at pre-K-8 Stokes School, has a classroom that can serve as an example for how other teachers could use STEM and discovery-based learning to meet students’ needs.

“That’s really all we do here, is discovery,” Butrum said.

The inquiry piece is threaded into projects, missions, and curriculum. Butrum tells students to build a bridge over two floor tiles with chairs, and then lets them figure it out through trial and error. He shows them a picture of a complicated two-dimensional design and has them build it in a three-dimensional model. Then he turns the image upside down and has students try again.

He assigns students a reading passage and then instructs them to build a scene from the book with legos. Then they take that scene and incorporate a digital aspect by inserting what characters are saying and creating a background through a story visualizer.

Butrum also uses Genius hour, a concept borrowed from the Google practice of permitting employees to spend 20 percent of their time working on something that fuels their passions. Students in Butrum’s class study their interests and then share what they found with the class.

“We just do crazy, off-the-wall things,” Butrum said. “Kids enjoy coming here.”

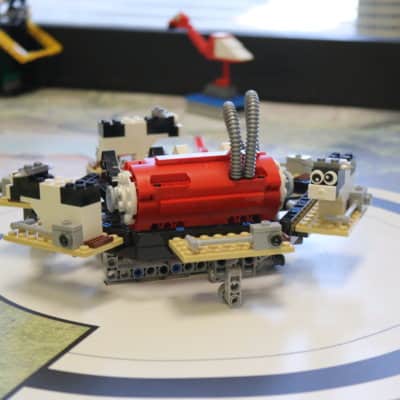

Butrum’s enthusiasm for the teaching tools is high, but his excitement is most evident when he talks about his FIRST LEGO League team. Students try out to be on the team, which meets twice a week after school. They work with a large board on top of a table-like surface and receive different challenges each year.

Specific materials come in a kit and students have to build attachments with legos, and construct and program a small robot to maneuver around the board.

Butrum’s team competes and, last year, they won the best teamwork award during a phase of the competition where the team is given a random assignment to create on their feet. When asked what assignment they were given, Butrum said he didn’t know; he was not even allowed in the room.

“It’s completely student-driven,” he said.

Butrum is also passionate about creating partnerships with businesses and organizations within the community. He said he wants to expose his students to as many real-life experiences as possible, and to connect what they do in the classroom with career options in the region. So far, Butrum said he has partnered with nine local businesses to support his Go Grow program.

In May, Butrum will follow a lesson on parachutes with a real-life observation at Fort Bragg.

“They’ll actually see what they’ve studied coming out of Galaxy planes,” he said.

Butrum has classes of middle schoolers every day and teaches K-5 students at different times during the week. DeCresie said it is helpful that Butrum doesn’t have a specific curriculum to which he must adhere. He said teachers like Butrum are not afraid to not know all the answers.

“Regular ed. teachers are sometimes not willing to take chances,” DeCresie said. And there are plenty of barriers for teachers who want to switch to an approach similar to Butrum’s.”

He said there are curriculum standards and test scores, and it is easy to get stuck in just doing what works

“AG teachers are not under that pressure,” DeCresie said. He said he wants to create a model to integrate Go Grow into the regular classroom.

“Let kids explore and your job is to fit the standards in,” Decresie said.

At present, students are identified as academically gifted in the third grade. But Butrum said he is glad he is getting to work with students starting in kindergarten. Many students, he said, are not challenged before the third-grade mark and end up not meeting the academic standard to be considered AG.

“We’re doing it early enough to grow into that,” Butrum said.

DeCresie agreed. He said there are students who come to kindergarten and need more difficult material than the traditional curriculum offers.

“If a kid already comes into kindergarten and can read, how beneficial is it for them to learn their ABCs?” he said.

DeCresie does not know if AG identification is necessary at the kindergarten level, but he believes there needs to be recognition that some students are advanced learners so that they are pushed to grow early.

“They could be a fast starter because of ‘xyz,’ but ultimately once everybody gets up to the same playing field, by third grade, they’re just average,” DeCresie said.

Ideally, both students are already performing well early on and those who demonstrate potential could have separate, specific pathways for development, he said. Right now, Pitt County schools can choose to either offer academic enrichment or exploratory-inquiry based learning.

Often, schools with high-poverty student populations do not have as many students who qualify for the academic enrichment pathway. But DeCresie thinks that in the current environment, it is not possible to offer both inside one school.

“I’d like to offer both of those,” DeCresie said. “I think both sets of those kids need to get that service: the ones that do demonstrate academics already, and then the ones that demonstrate potential … but I don’t have the support or personnel to be able to do that.”

DeCresie’s passion for AG education precedes the Go Grow program. DeCresie’s wife introduced him to the work when they started dating back in the mid-90s, and he has been directly involved in AG work since 2001.

Eventually, DeCresie said he would like Go Grow lessons to move beyond STEM to anything that interests students, whether that be music, art, video games, or the outdoors.

DeCresie and other district leaders have started writing creative lessons for ranging grade levels on everything from etymology, origami, and Billy Joel, to the death penalty. This document gives overviews of lesson plans and details on each.

“Ultimately, I want a school to identify the top 10 percent of that group,” DeCresie said, “and ask them, ‘What do you want to do?'”

This school year is Go Grow’s first year. DeCresie intends to use this plan cycle (2016-19) to give each school in the district time to find what exactly the program will look like for their students.

“We’re letting all the schools figure out what works and then we’ll look at it and ask what seems to work best,” DeCresie said. “Then we’ll say, ‘Let’s adopt those practices into our new (2019-22) plan.'”