The committee tasked with addressing the needs of the “whole child” revealed its initial findings from a pilot program on Thursday. The Whole Child NC committee convened to discuss progress of the program designed to examine issues outside of academics in 11 school districts. The group, a collection of representatives from different state, local and nonprofit agencies across the state, also unveiled its assessment tool.

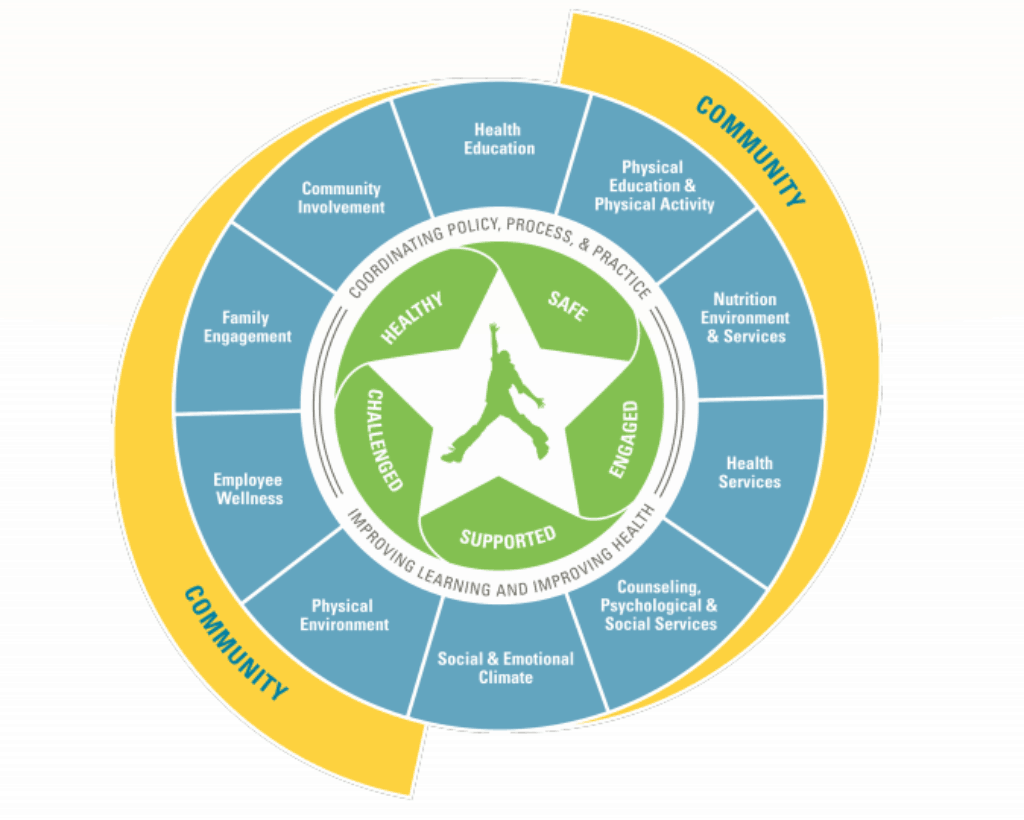

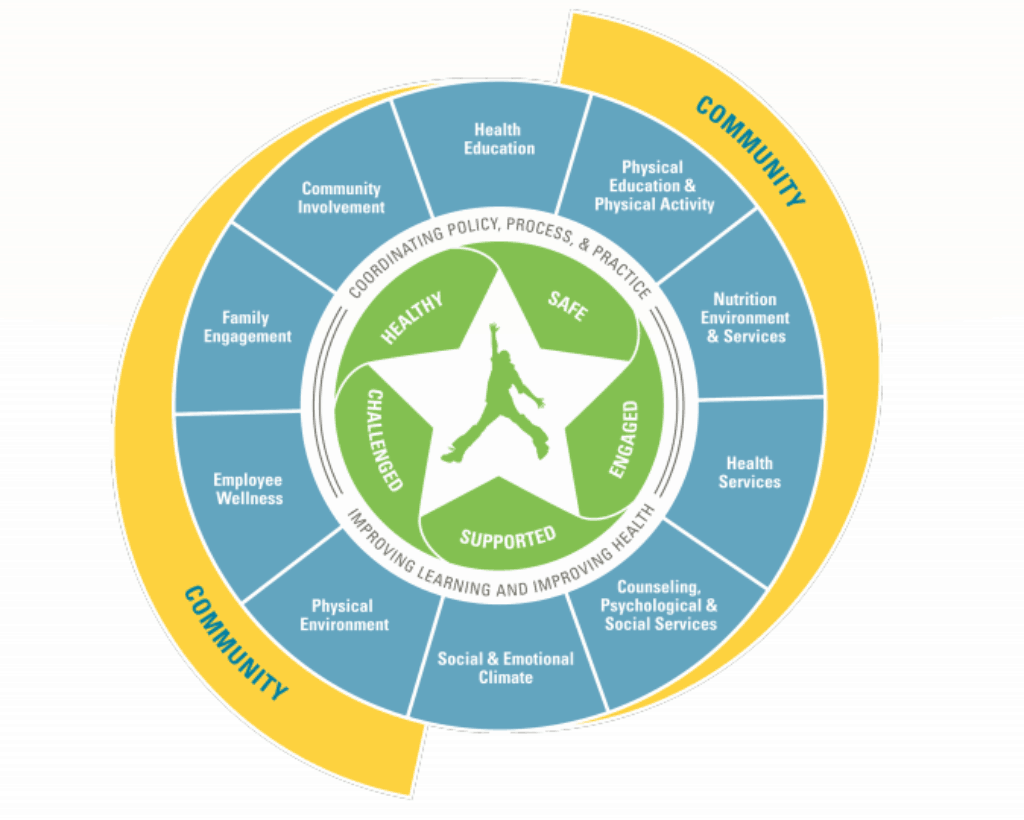

The Whole Child initiative shifts away from an exclusive focus on academic achievement and towards the idea that a student’s success at school is inherently tied to comprehensive health and well-being. The model, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), encourages participation by multiple stakeholders including medical professionals, counselors, nurses, psychologists, state agencies and nonprofit organizations.

The initiative recognizes that academics do not occur in a vacuum; under the model, school systems will be fully integrated with other providers to address student needs in 10 key component areas.

Credit: NC Healthy Schools/Whole Child Committee

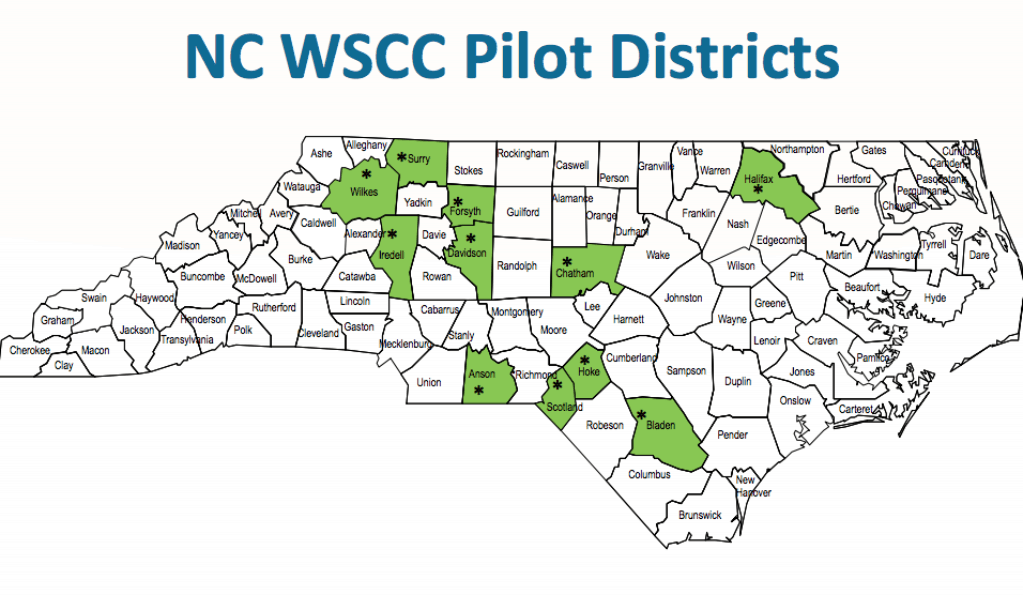

The North Carolina initiative identified 11 school districts for participation in the three-year pilot program. The districts had to agree to collect specific data about behaviors and practices. In addition, the local health director and superintendent of any selected districts also had to agree to attend School Health Advisory Committee meetings in person and engage other community leaders.

“It’s tough, because everybody talks about whole child, but then when the rubber hits the road and it is time to buy in, it gets tougher for folks, because it is like, ‘Well, testing is next week,” said Ellen Essick, NC Healthy Schools section chief. “And so really making that commitment is what we are asking these 11 LEAs (local education agencies) to do and to make this a priority.”

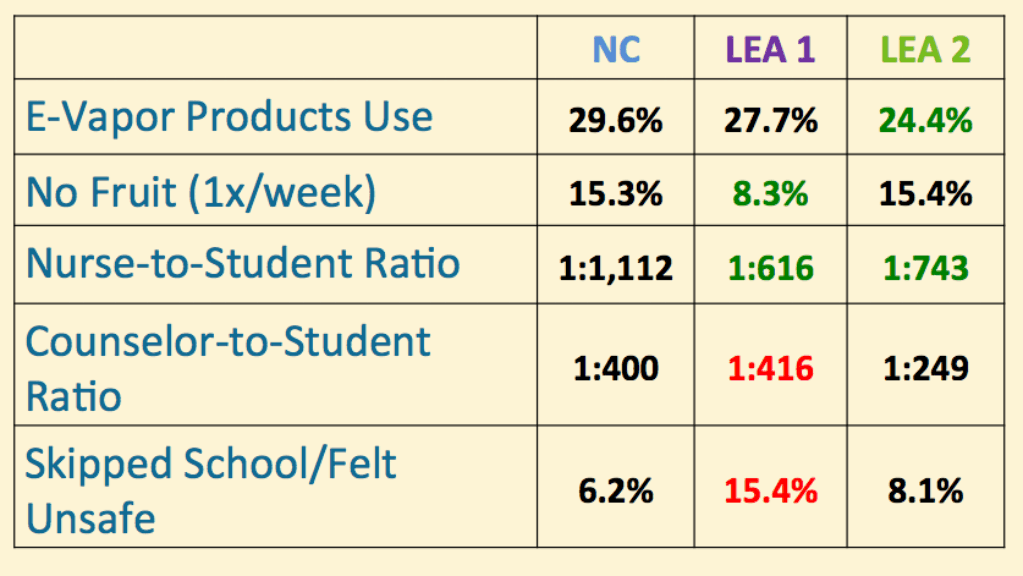

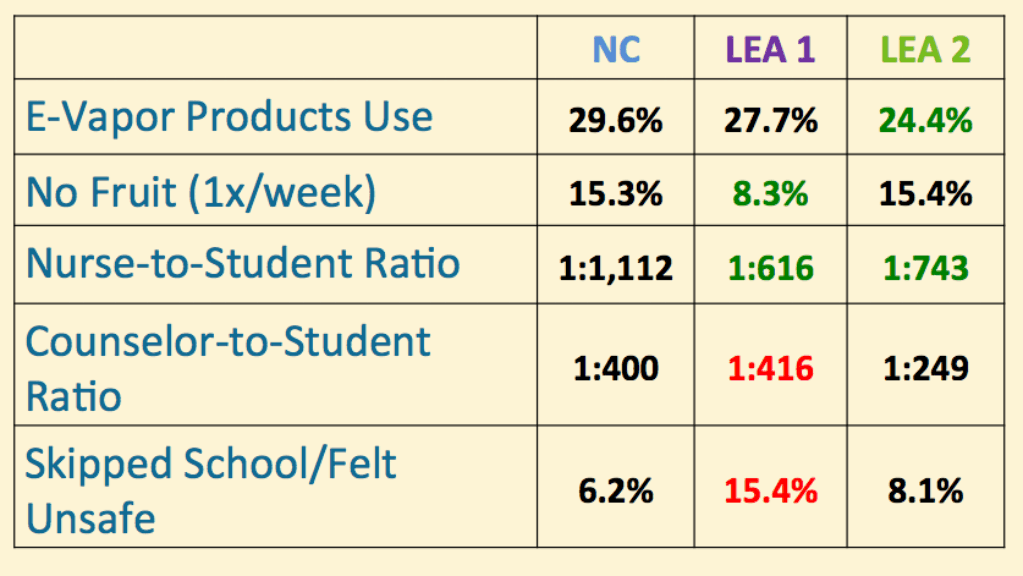

The Whole Child committee presented the initial assessment tool used to evaluate schools system’s performance in the 10 component areas of the model. The data-driven assessment mechanisms are an intentional practice designed to enable pilot districts to understand their strengths and weaknesses. Essick reviewed the assessment tool with committee members.

“I think the mantra of our work for years has been, ‘Healthy children learn better,’ and we finally have national data and we finally have research data that supports that work,” Essick said. “But it is getting schools to use their data and see some of that movement as well.”

Mary Jane Akerman, a representative from the Thomasville City School system, one of the pilot programs, said they are excited about the new assessment.

“A lot of our data has been more of the bean-counting data so far because the people who were in leadership positions knew the needs and knew what we needed to address because of their connections in the community, but we haven’t always looked at where were we and where are we now,” Akerman said. “And that’s the thing we are most excited about with the pilot. Now we are going to have some real strong points to say this is where we moved, or this is where we didn’t and what can we do to address that.”

Credit: NC Healthy Schools/Whole Child committee

Essick led the group through an exercise that examined how policy influences practices and how, at other times, practices influence policy. Kathy Blankenship, assistant superintendent at the division of state-operated healthcare facilities at the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, shared a challenge from a preschool program in Burke county.

“We do a lot of research and development of programs and training, but we also go into the homes and look at families,” she said. “And we came to realize that parents were telling their teachers, their staff, about not having food for the weekend and not being able to access things that they needed.”

Teachers provided the families with names and numbers for food access, and in some instances, drove families to resources. But the solution had negative effects, Blankenship said.

“What we found out was that the stress levels of teachers was so high because they were literally taking it home with them.”

Blankenship said teachers had to understand that it was acceptable to coach families about how to access what they need. They also developed a curriculum about good choices around family budgeting for those who were using funds for non-food items. Eventually, they recruited other families as mentors for education about good choices so the staff could take a step back, Blankenship said.

The Whole Child approach, Essick explained, must consider both policy and practice in order to succeed.

Representatives from two of the 11 pilot programs — Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools and Thomasville City Schools — reported on their districts’ successes.

The Winston-Salem/Forsyth County school system has a School Health Advisory Council (SHAC) that approves goals in each of the 10 model component areas.

Dr. Stephanie Daniel, executive director of the Forsyth SHAC and a faculty member at Wake Forest School of Medicine, spoke about the importance of collaboration. “It has also been really helpful for us to have decision-makers at the table. From many of the organizations…we have at least one decision-maker from that organization at the table. It just helps to move things along, and decisions can happen more quickly when you have the decision-maker at the table.”

Dr. Daniel outlined one example of a SHAC success: Operation Zero Suspension. The Forsyth county school superintendent asked SHAC for assistance in reducing suspensions for health assessment and vaccination noncompliance. The effort reduced suspensions of kindergartners from 333 in 2013-14 to 289 in 2014-2015. By offering assessments through mobile clinics and educating medical providers, the operation reduced the number of suspensions to 129 in 2015-2016. By the latest school year, 2016-2017, the number of kindergarten suspensions for noncompliance fell to 90 students.

Dr. Daniel credits the success to SHAC education and outreach efforts. “It really was a system effort and it really was a community collaborative,” she said. “It wasn’t just one agency or one person that worked together to move the needle on these numbers.”

Thomasville City Schools, another pilot program location, also reported success with the comprehensive Whole Child initiative. The district has used data from the assessment tool to change the way it serves nutritious foods, particularly fruit, in the school system. The changes were prompted by recognition that the district’s numbers were not as high as those of other districts.

Marie Pitre-Martin, deputy state superintendent at the Department of Public Instruction, said continued data collection is a key component of the Whole Child model. Pitre-Martin said the biggest challenge for the initiative will be scaling up to a statewide program.

The committee will meet again in three to four months to evaluate progress, share data findings, and assess the viability of a statewide offering.

Watch the full committee meeting:

Part two: