I started my career in the mid-1990s as an admissions staff member and met with many individual students (walk-ins, as we called them) about how to gain admission. The university was focused on transfer with a high proportion of first-generation college students, and in-turn, I met with students seeking to transfer, many of whom attended a community college hoping to one day earn a bachelor’s degree. As a first-generation and transfer student myself, I took pride in working with those navigating the transition.

At that time, community colleges in North Carolina were on the quarter system (unlike the semester system at UNC System campuses), the community colleges did not have common course numbering, and the university where I worked had different credit equivalencies for different community colleges across the state.

Unfortunately, these conditions led to many difficult conversations with prospective community college transfer students: “I’m sorry, but some of your credits won’t transfer” (lost credits); or, “You will receive transfer credit for these courses, but they won’t count toward requirements for your major,” (excess credits). At that time, I didn’t know what I didn’t know, and my primary perspective was that students were making mistakes or were receiving bad advice — the wrong perspective for someone supposedly working to further higher education access and success.

In the years that followed, dedicated leaders in North Carolina created the first comprehensive articulation agreement (CAA), which, among other things, provided a clearer path toward transfer to a UNC System campus and offered guarantees of meeting general education requirements when following guidelines. Much of this was also enabled by the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) implementing common course numbering across their colleges to allow for consistent transfer of courses no matter where students began.

The 2014 revision of the agreement and subsequent updates have improved transfer by further outlining a core of NCCCS Universal General Education Transfer Component (UGETC) courses that should count toward any major, mandating that universities publish Baccalaureate Degree Plans to guide student course selection, and encouraging the early completion of ACA 122: College Transfer Success (a course designed to help community college students navigate transfer choices). Signatory institutions among the North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities (NCICU) approved a similar agreement in 2015, following their prior endorsement of the original plan, offering more seamless transfer for NCCCS students into private colleges and further demonstrating the vast transfer ecosystem in our state.

In those early days, I generally assumed that the inefficient transfer of credit was just part of the process, and wondered why students made “mistakes” when scheduling community college classes or enrolling in programs. I regularly met with students who had completed an Associate in Applied Science (AAS) degree, which is typically more focused on career/workforce preparation. These students often experienced the loss of credit when transferring, especially when compared with those earning transfer-oriented degrees like the Associate in Arts (AA) or Associate in Science (AS) degrees. It wasn’t until some years later, after I had worked in the community/technical college sector and had conducted my own transfer research, that I realized how my early career mindset devalued the workforce development mission of community colleges and completely failed at understanding transfer from the student perspective.

Recently, with support from the John M. Belk Endowment, our research team at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte has begun looking more closely at how community college students experience transfer in North Carolina. The data fundamentally confronts the assumptions I made more than 25 years ago, reinforces the perspective I gained when working in the community college, and has driven our recent work on transfer student experiences.

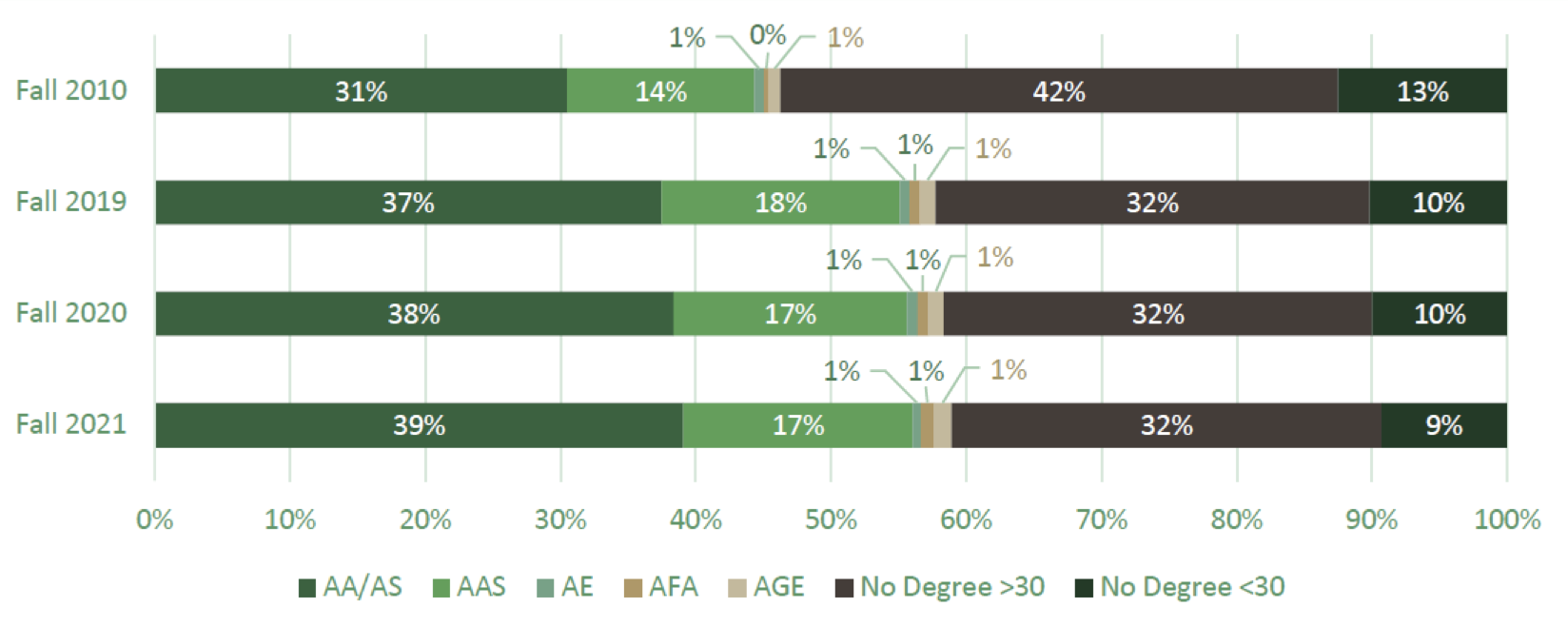

Credentials at transfer

North Carolina has seen an uptick in the percent of students transferring with associate degrees, which is a great first step for future success and helps the state meet the myFutureNC goal of reaching 2 million North Carolinians with a high-quality credential or degree by 2030.

However, many of those students (around 1 in 6) make the transition with an Associate in Applied Science (AAS) degree, the more workforce-focused degree. While uniform (statewide) and bilateral (between individual institutions) articulation agreements do exist for certain technical degrees through the commitment of institutional and program leaders, AAS degrees are not included in the primary statewide CAA. Regardless, the practical reality is that students are deciding that the AAS is a transfer degree, and we can either choose to support them or not.

NC Community College to UNC System Transfer Prevalence by Degree Status

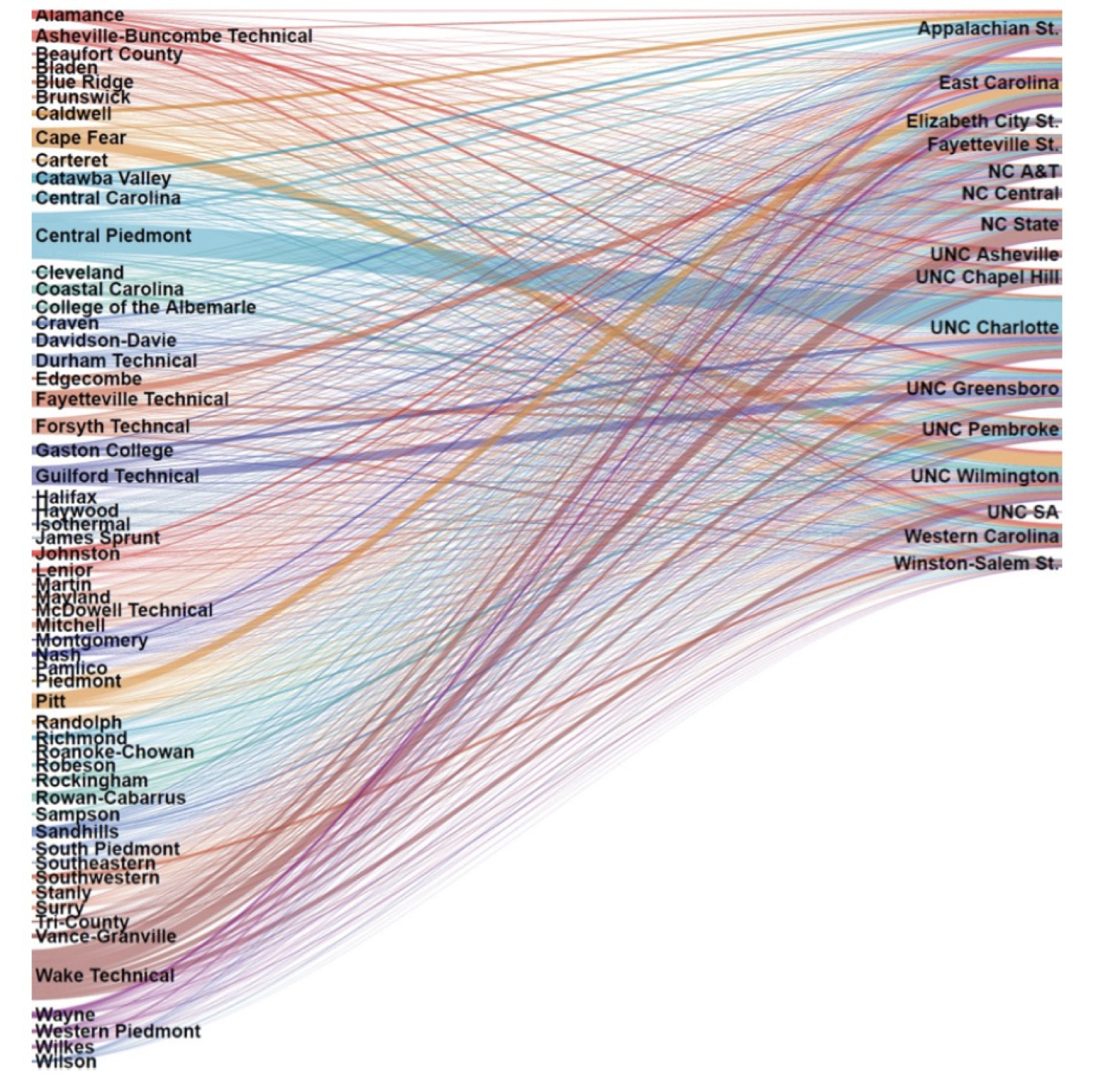

Transfer destinations

In Fall 2021, NCCCS students transferred to UNC System campuses along 691 distinct patterns, not even accounting for the numerous paths across different majors within those campuses. The diagram below shows these many transfer patterns — wider linguini–shaped lines represent more prevalent patterns while thinner angel hair-shaped lines show patterns with just a few students.

NC Community College to UNC System Transfer Enrollment Patterns

Primary feeder patterns

Decades ago, I held a common assumption — that community college transfer students go to a nearby university. We see the local focus playing out every time transfer partnerships are developed between neighboring institutions. At face value, this is a worthy effort to enhance transfer experiences of students; however, there is more to the story.

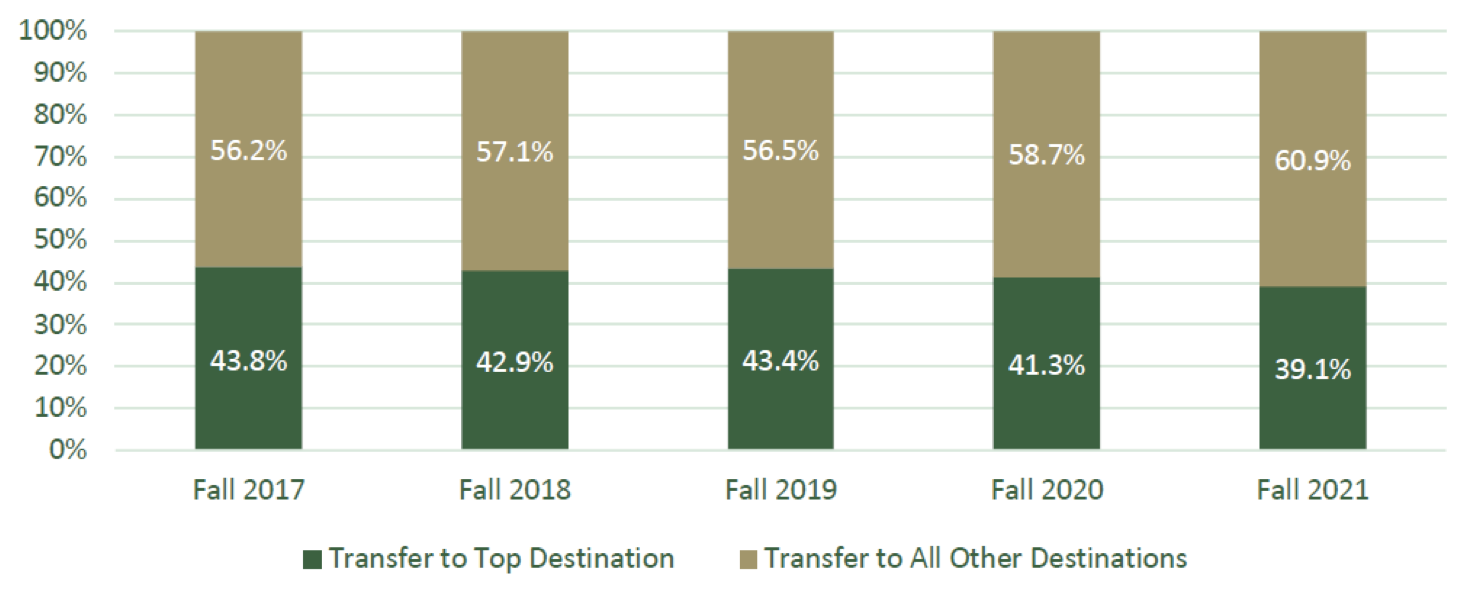

While the 691 transfer patterns offer evidence that students follow many pathways, we also tracked “primary feeder patterns” (i.e., the university to which students most commonly transfer from a particular community college). When first running these numbers on the Fall 2017 data, I was very surprised that only 44% of students followed the primary path. However, the trend has shown that even fewer are now following primary patterns — down to 39% in Fall 2021.

This is a trend with implications for students and their advisors, since they need to choose among the vast institution and major options across the state to ensure they are taking the courses that will help them avoid lost or excess credits. The emphasis on local transfer partnerships may ease the path for many, but it does not create practices that serve all students in the same way that statewide efforts do. Once again, this is not something I would have expected, or even considered decades ago, as I assumed that the transfer ecosystem was much smaller.

Percent of NC Community College to UNC System Transfer Students Following the Primary Feeder Pattern

A lot has changed over the past 25+ years, from state transfer policy, heavy lifts like common course numbering, and dedicated leadership continuing to work on improving the conditions for students locally and across the state. I am heartened by North Carolina’s track record in working to improve systems, and I see state and institutional leaders working toward those ends.

At this time, though, our team’s study shows that students are still experiencing complex transfer choices with challenges identifying and following appropriate paths, and thus many students are still hearing that courses won’t transfer or count toward their majors.

We recently released a research brief that provides the voices of transfer students, following interviews with 103 community college students both before and after transfer. Their narratives are powerful, bring to light some of the experiences of transferring with and without certain degrees, consider how they select universities, and describe the ways systems are helping to ease the transition or serve as barriers to their successful transfer.

Go here for additional information about the data in this article and related reports.