On the evening of April 14, 1865, Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln went to a play at Ford’s Theatre where Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth shot the 16th president in the head. The grievously wounded Lincoln died an hour after dawn the next day in a rooming house across the street.

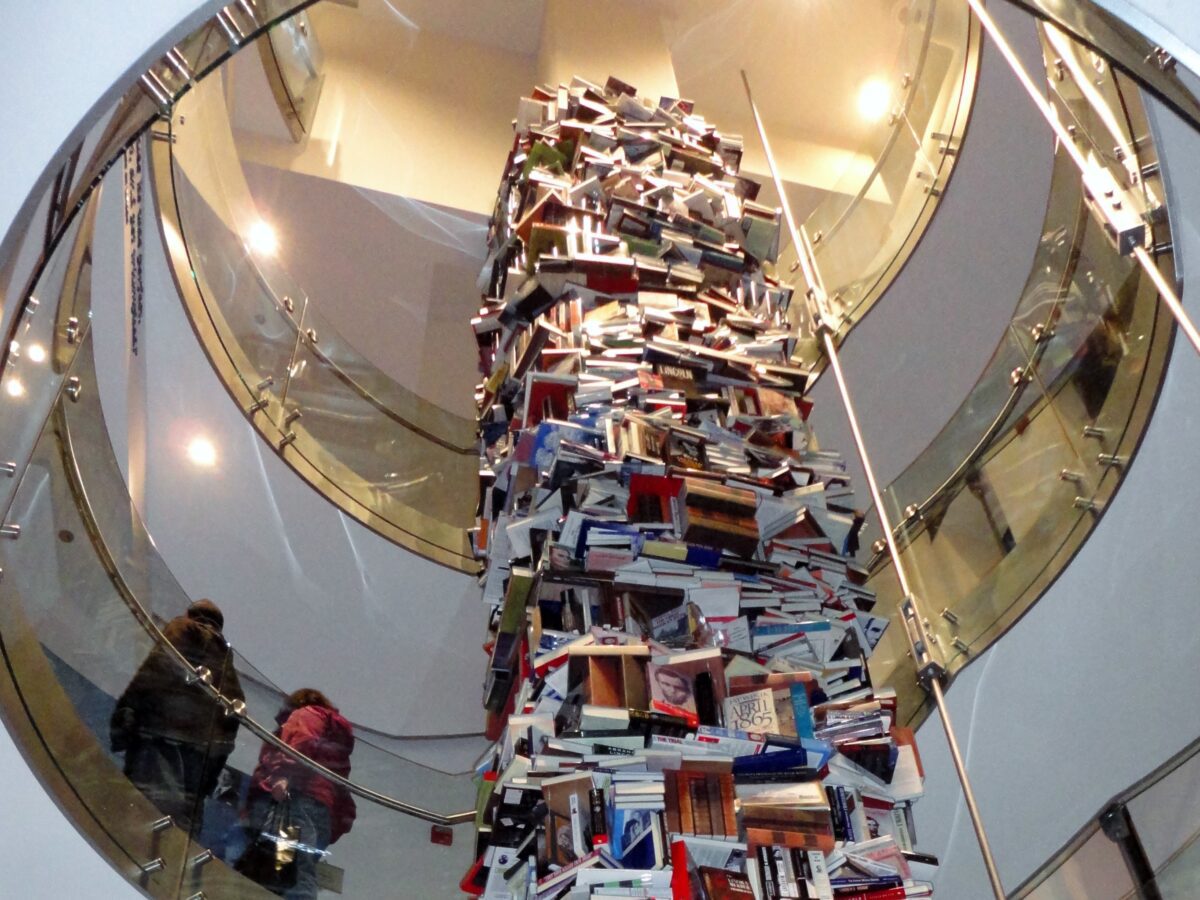

Now at that site on 10th Street NW in downtown Washington, the Ford’s Theatre Society has erected an impressive three-story stack of books on Lincoln and his presidency. The book tower dramatizes how Lincoln, as the subject of as many as 15,000 titles, still commands popular fascination and historical research.

The book tower implicitly delivers another message relevant to the renewed efforts in the North Carolina General Assembly to impose mandates on teachers of history and American government in public schools, colleges and universities. The message is that the study of history and democracy is a dynamic enterprise of examining and re-examining moments glorious and inglorious, grand achievements as well as enduring injustice. It involves inquiry and interpretation not reducible to just-the-facts of names, events, and dates.

The state House has passed a Republican-sponsored bill that would enjoin public school teachers to refrain from suggesting that anyone today is responsible for discrimination by persons of his or her race or sex in the past. Among other provisions bearing on race and gender, the bill would have teachers avoid making any student feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress.”

This legislation comes four years after the North Carolina legislature mandated a personal finance course that, unfortunately, inflicted the collateral damage of reducing American history to a one-semester requirement in high schools. The upshot is both to constrain public school teachers from comprehensive history instruction and to sanitize and degrade what ought to be a supremely engaging subject for adolescents as they prepare for full citizenship.

Tellingly, on the same day it passed the bill constraining high school history, the Republican-majority House also approved a bill to require at least three credit hours in American history or government for graduation from a North Carolina university or community college. What’s more, the legislation dictates content of the course and that the final exam must represent at least 20% of a student’s total grade.

The legislation prescribes a reading list of important documents, including the U.S. and N.C. constitutions, as well as Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and Gettysburg Address. It also would have students read “at least five essays from the Federalist Papers.”

Set aside the issue of whether a legislature should dictate a syllabus or grade. Consider the tantalizing possibility of a course that would have students discuss and debate the General Assembly itself in the context of the Federalist Papers. Of the 85 essays published in 1787-88 in support of ratification of the Constitution, students would read these five: Numbers 10, 47, 48, 51 and 73.

In these essays, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton did not use the contemporary terms of super-majority or veto-proof majority. Still, they understood “the propensity of the legislative department to intrude upon the rights, and to absorb the powers, of the other departments.” They did not address gerrymandering, but they worried about what they considered the negative effects of “faction.”

They argued that an American democracy in which people vote for their representatives would be tempered by separation of powers – between states and the federal governments and among three branches of government at each level. They described the United States as “the compound republic of America.”

In Federalist 47, Madison wrote, “The accumulation of all powers legislative, executive, and judiciary in the same hands, whether of one, a few or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.” In Federalist 73, Hamilton wrote that the executive and legislative branches “ought not to be left to the mercy of the other, but ought to possess a constitutional and effectual power of self-defense.”

In Federalist 51, Madison famously wrote, “But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

Of course, today’s faculty and students live in a far different world economically, technologically and demographically than the late 18th Century when the Federalist Papers were written by brilliant yet flawed men who initially reserved democracy to white men with property, many of them owners of slaves. Today’s students live in an environment of partisan polarization and instantaneous flows of information and disinformation in their hand-held devices. The modern North Carolina surely can provide and support knowledgeable teachers to engage their students in making history come alive and relevant through applying such foundational documents as the Federalist Papers and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to their own emerging participation in this democratic republic.