When we began co-teaching virtually almost four years ago, we realized that the 161-mile physical distance between our schools would not be our biggest challenge.

Instead, we quickly learned that disparities in student access to technology and the logistical hurdles of teaching in vastly different school districts were the main obstacles.

Our student demographics reflect the diversity and socioeconomic differences of our respective regions. At Druid Hills Academy in Charlotte, where Keith teaches, students are majority Black and Latino and live in a metropolitan area. Amanda teaches at the Catamount School in Sylva, a predominantly white community in a rural area of western North Carolina. As a result, some of our students lacked access to technology and internet connectivity.

Additionally, our schools operated on different calendars, and our schedules did not always sync up favorably. District and school policies would sometimes hinder collaboration when certain resources available in one district were blocked in another.

A curriculum standard brought to life

Despite these challenges, our shared recognition of the power of co-teaching and a desire to explore its potential compelled us to give it a try.

We met during our year-long fellowship with the Kenan Fellows Program for Teacher Leadership in the summer of 2019. Although we came from different backgrounds, we found common ground in our teaching approaches and a mutual interest in leveraging co-teaching to enhance student learning.

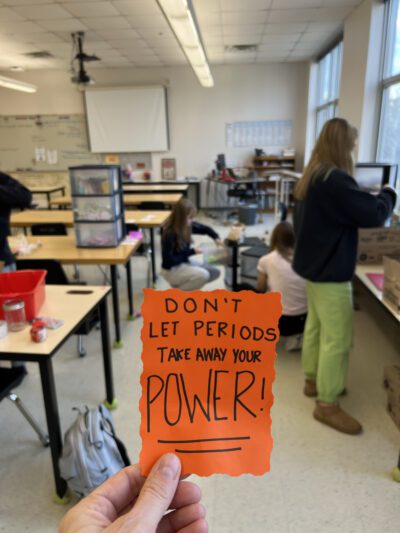

With a shared vision, we began a project-based learning unit focusing on water quality — a subject required by North Carolina’s eighth-grade curriculum standards. Our unit comprised an entry event and various checkpoints to facilitate online learning. Students were tasked with creating teaching tools to advocate for the recognition of water quality as a critical resource transcending socioeconomic boundaries. At the completion of the unit, students delivered products that addressed issues of environmental stewardship and ensured clean water access for different communities. The students delivered their product presentations before an audience of educators, students, and stakeholders within the water quality industry at UNC-Charlotte.

Our collaboration was facilitated by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for STEM Teachers, which we each received in 2021. The award gave us the resources to create a student website for our collaborative project-based learning unit. The website served as a hub for accessing course materials, sharing content, and exchanging ideas. The digital platform also allowed for multimodal methods of participation which enabled students with different learning styles to take agency in their learning.

Initially, challenges such as unequal access to technology hindered our progress. However, through partnerships with stakeholders, we ensured equitable access to laptops and internet hotspots for all students involved.

A key to the success of our collaboration has been providing feedback for student work. Ensuring that students have tangible feedback is critical to reinforcing their learning. Thus, it was good to see that students responded positively to online instructions and received teacher feedback virtually rather than in person.

Bridging communities

Following two weeks of digital work and parallel learning between our classrooms, the students met in person for the first time at East LaPorte Park on the Tuckasegee River in Cullowhee. Having worked together online for a few weeks, the students had a nice rapport and dove right into collecting bioindicators to examine the water quality of the river. Following the water activity, the students gathered to revise their shared projects.

As educators, we recognized that if we gave students the autonomy to work together, they could facilitate their own learning and recognize the concepts that we wanted them to understand. Best practices for student learning dictate that peer interaction is a driver of academic success. By allowing students from different districts to work together, they were able to share their unique personal experiences involving water stewardship.

Each time we do this project with our students, we allow them to figure out the collaboration dynamics independently. As all of our students are progressing through the stages of adolescence, they are well aware of the racial and cultural differences that exist between them. That is what makes this collaboration so powerful. Despite their obvious differences, they are still focused on the task at hand. The students ensure tasks are assigned and completed equitably.

For educators, the benefits of cross-district teaching are just as rewarding. For example, teachers often reflect on new ways to get more student engagement and buy-in on certain academic topics and concepts. It helps to have a collaborative partner to brainstorm and bridge ideas that will support and grow student learning.

The expertise shared by teachers is our strength. Even if we cannot meet face to face, digital tools allow us to collaborate and support each other. Using these tools, we connect to plan and facilitate project-based learning for our students. This approach allows us to incorporate experiential and place-based learning with our science standards and encourage collaboration between students in different communities.

Watch our “Not Your Average PD” session here to learn how you can incorporate collaborative online teaching in your classroom. And learn more here about Not Your Average PD, a free online professional development series for educators presented by the Kenan Fellows Program for Teacher Leadership.