It’s Tuesday at Harambee and the gym at the International School at Gregory is having trouble containing the chanting, clapping, and cheers.

About 50 students — called scholars — are spread out on the floor. Ja’Quay Locke, a lanky rising Holly Shelter Middle School seventh grader, was locked in on one of the student leader interns (SLIs) — Kaylee Limeberry — as she stirred the scholars up into a frenzy.

The whole gym was clapping. Dancing. Stomping.

Despite physically staying six feet apart, there was no distance between their voices.

“Are you hype? Are you hype?”

Nothing is said at Harambee.

It’s sung. It’s shouted. It’s chanted.

The group answered as one.

“Yeah. I’m hype. I’m hype.”

The call and answer go on for a bit. Each time the Limeberry calls out, the energy level rises until they get to the final answer.

“I’m hype for Freedom School.”

The whole gym stomps and dances.

“Turn up, turn up, turn up, turn up…”

Freedom School scholars — white, Black, Hispanic — begin every day with Harambee, which means “let’s pull together” in Swahili.

It’s the Freedom School way.

Freedom School comes to Wilmington

This is the first time the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom School program has been held in Wilmington. Rooted in the Mississippi Freedom Summer project of 1964, the six-week cultural and literacy program stokes the scholars’ passion for reading and builds up their self-worth and sense of community.

Freedom Schools arrives in Wilmington just as the United States faces a reckoning over systemic racism and police brutality, a truth the program doesn’t shy away from. In fact, the curriculum was already tackling these issues. The program seeks to affirm and discuss the persistent problems scholars see and live every day and the importance of civic engagement to make meaningful change.

“The heart of Freedom School is letting our scholars know they can make a difference in their families, in themselves, in their communities,” said Keisha Robinson, the site coordinator in Wilmington. “We’re building them up here but they’re taking it someplace else with them.”

How it works

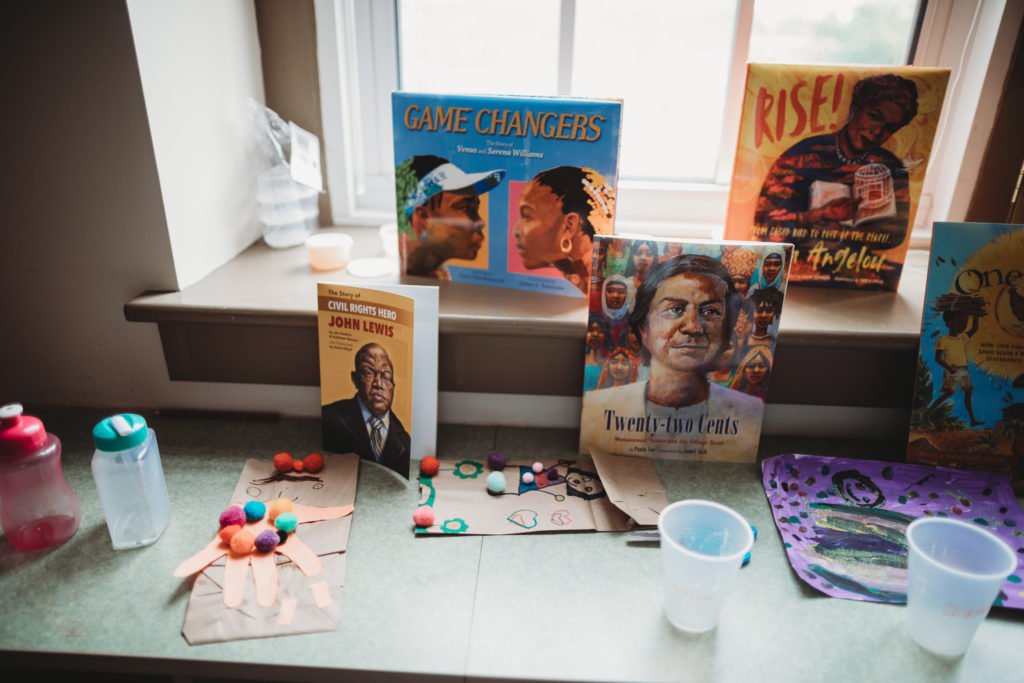

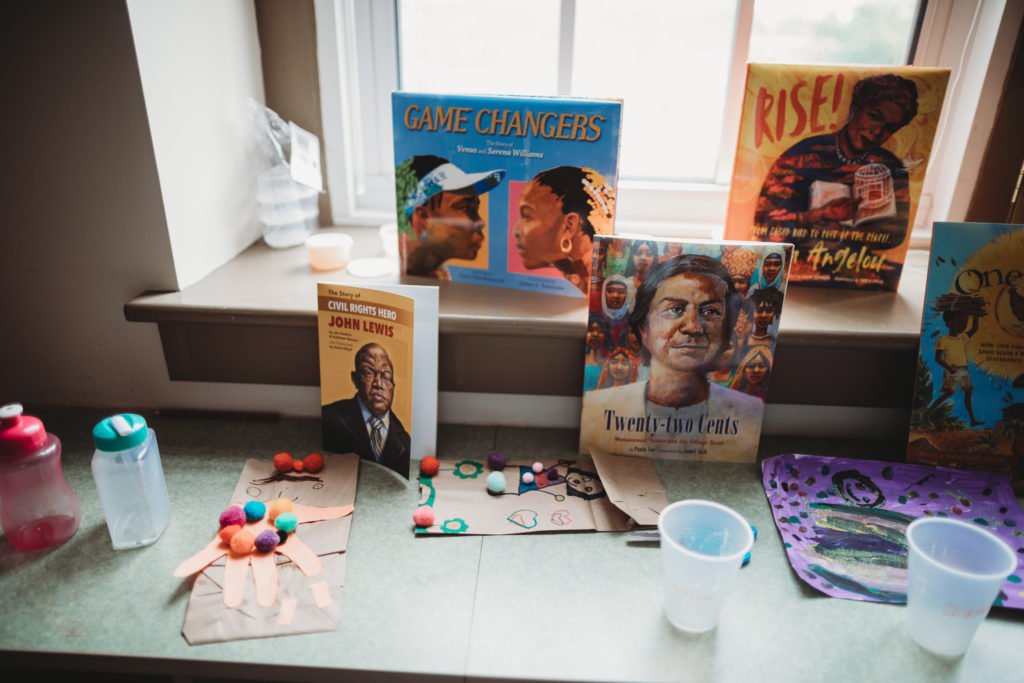

Freedom Schools is led by SLIs, students recruited from UNC-Wilmington and East Carolina University. They lead class discussions in the morning and activities like art, step, drama, and athletics in the afternoon. Before the program started Robinson sat down with the staff and learned all their hobbies and built the afternoon activities around them.

“They’re bringing a lot of what they know to it,” Robinson said.

Keith Miller, a senior at UNCW studying psychology, took the Freedom Schools job after hearing about it from a fraternity brother. It was an opportunity to work with children. Miller said the Freedom School curriculum challenges the students to ask questions and think critically about not only what they’re taught but what they see in the community. For some of the students, this is the first time they’ve read books with characters facing the same issues they do every day.

“It challenges them to ask why,” Miller said. “We’re getting real.”

Locke said one of his favorite books was The Road to Paris by Nikki Grimes. The book is about Paris, a nine-year old, biracial girl who is in foster system after her father leaves and her alcoholic mother can’t take care of her and her brother. Paris is separated from her older brother Malcolm — who has protected her — after they run away from an abusive foster family.

The book led to conversations about violence, neglect and racism. Topics that aren’t readily discussed in current curricula. Locke said he felt safe in the classroom and said the conversations helped him, declining to get into specifics.

Locke said he identified with Malcom.

“He is kind of like me,” Locke said. “I like helping people.”

Like Locke, Maleya Ross, an 11-year-old rising sixth grader headed to Trask Middle School, identified with the characters and the situation.

“It sounded like a real story to me,” Ross said.

Miller said the curriculum is relevant for today.

“They take on racism, sexism, police brutality, and gender,” Miller said. “I really think it is perfect. Easy to be relatable.”

While the classes take on big issues, the structure was loose and focused on discussion more than rout learning. The classrooms were a place to explore and discuss. Before the first class, Miller made a pact with his scholars. He’d give his all if they did. They even signed a contract. Miller sees it like a coach/player relationship.

“Just because I’m the teacher, I can learn from them,” Miller said. “This sets them up to be self-aware and be someone.”

Serious lessons

Down the hall from Miller’s classroom, Dwayne Altman–Leach was leading his elementary school aged class in a discussion of Lillian’s Right to Vote: A Celebration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The book follows Lillian — a 100-year-old African American woman — as she heads the polls. Along the way, she recounts her family’s journey to gaining the right to vote. The book was published to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Sitting in a circle, each scholar took a turn reading one page. With each page, there was a short discussion with Altman–Leach giving prompts. When they got to a part about voter suppression, Altman–Leach threw out some hints.

“What group burned crosses?” Altman–Leach said. “This gang has 3 letters. Starts with a K.”

It took a minute, but the scholars figured out he was talking about the Ku Klux Klan.

“They’re racist butt faces,” the same Black girl said.

Part of the Lillian’s journey highlights the systems in place to suppress the Black vote like poll taxes and exams, which led to a conversation about who had the right to vote. At one point, he wrote “all men are created equal on the vote” as they talked about who had the right to vote.

Men. Not Black men. Not women. Just white men. It angered the class.

Altman–Leach pointed out election officials were not asking white voters the same questions. The scholars were aghast.

“That is messed up,” the Black girl said.

These kinds of conversations are at the soul of Freedom Schools. The only way to engage the students on the importance of civic engagement is to show them the fight needed to get it. The lesson was clear. Voting is not a right to be squandered.

The way

Civics and history are cornerstones of the curriculum. But Freedom Schools has loftier goals. They are creating a new generation of community leaders who understand the past and where they want to go. Robinson said it is one of the best ways to give students the confidence to be critical thinkers and create a community that can build a better world.

“We’re here to serve them and as scholars it is their job to take everything they have and make something more of it,” Robinson said.

Another benefit of the program is how it closes the achievement gap. A 2010 study of the program in Charlotte, North Carolina and Bennettsville, South Carolina found more than 90% of scholars suffered no summer learning loss after attending Freedom Schools. A Kansas study found scholars improved their reading by two grade levels after attending the program.

This year there was one Freedom School program. In five years, Robinson wants to see one at every elementary school in the county.

“We’ve got to create a new culture,” Robinson said.

Few students took to Freedoms Schools like Locke. From entertaining the other scholars at breakfast to Harambee where he was one of the loudest voices in the gym to the honest discussions in class, Locke found a place where he could not only explore his own lived experience, but build a community to help him handle it.

The Freedom School way gave him confidence.

“[At] my regular school the only time I can express myself is at recess,” he said. “Here, all day, I can express myself with actions and words.”

It’s Tuesday at Harambee and the community being built over six weeks will last long after the echoes fade from the gym.