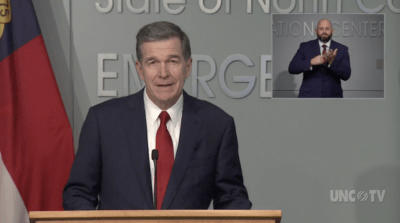

On Tuesday, Gov. Roy Cooper announced the preferred reopening plan for North Carolina schools. The plan spells out details to allow for in-person or virtual learning and prioritize safety measures to mitigate COVID-19 transmission among children, staffers, and teachers.

It’s refreshing to see attention focusing on children’s well-being, as they have suffered many losses during the pandemic. Now we must ensure that we support students, staff, and teachers as schools reopen by providing the resources schools need and defining school-specific metrics to inform the risks and benefits of keeping schools open.

As pediatricians, we are bearing daily witness to the pandemic’s devastating impact on children. School closures, initially required to slow the spread of COVID-19 in our communities, have led to countless losses for children. While the world focuses on ill adults, children are quietly experiencing enormous losses not captured within news headlines. Children have been falling behind on education, those with disabilities were not receiving crucial services, food insecurity rates doubled, peer contact plummeted, and already-high obesity rates were rising. Parental job losses are plunging children into deepening poverty. Immunization rates have markedly dropped, threatening resurgence of previously preventable diseases.

Our government officials face difficult decisions on how to operate schools this fall in the midst of an unrelenting pandemic. There is understandable hesitation in plowing ahead with school reopening given the climbing numbers of cases. Yet discussions about school reopening must include the established emotional, developmental, and health costs of keeping children away from school, classmates, education, food, and physical activity. As a recent American Academy of Pediatrics statement laid out, decisions for this fall should prioritize children being physically present in schools, where feasible. A well-thought out plan B hybrid approach, combining developmentally appropriate virtual learning with in-person classes, may also be reasonable.

However, for the overall goal of keeping children healthy and safe, ceasing in-person education completely and switching back to virtual learning should only be used as a last resort. There is now increasing evidence that schools may not be a main driver of coronavirus community transmission. Therefore closing schools may inadvertently move us in the wrong direction for overall harm reduction for children.

The role of children in transmitting SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is still being evaluated. The pandemic has seen a surprisingly limited number of pediatric infections, most of them mild. This pattern led to the early theory that children may frequently be asymptomatic spreaders of the infection. However, increasing evidence suggests children may not be significant sources of asymptomatic transmission of the virus. Countries such as Denmark and Norway reopened schools after achieving a national reduction in case numbers, and these countries have not had a resurgence of cases among school children, their families, or their teachers. Yet, Israel experienced outbreaks in schools and reclosed schools as a result.

Meanwhile, aggregate studies from multiple countries suggest children are less likely than adults to become infected from an infected household member. Children also appear less likely than adults to transmit the infection to other household members. Groups of children may be less likely to create new outbreaks than gatherings of adults, making restaurant openings more likely to contribute to outbreaks than school reopening.

Teachers and school staff have valid concerns that returning to work may expose them to new settings where coronavirus can be transmitted. Yet, it must be emphasized that the largest risk for school staff will be picking up the virus from co-workers who they congregate with, eat with, or commute with. Health care workers have been able to reduce virus acquisition from patients via universal masking, yet virus transmission events have continued in unmasked settings with co-workers.

With schools opening, we should mount a focused effort to document transmission patterns among children, teachers, and staff. Resources should be immediately made available to school systems for protective equipment and cleaning supplies, and importantly, additional staff for reduced class sizes plus larger teaching spaces to allow for social distancing. Furthermore, policies on the length of time that classmates must quarantine after a classroom exposure to the virus should be refined to limit continual disruptions of moving between virtual and in-person learning for both children and caregivers.

Finally, to make informed decisions about managing schools throughout the fall and winter, we must develop child-specific metrics to monitor the virus’ spread in children’s settings. Potential metrics include numbers of outbreaks tied to childcare or school settings, proportion of children and school staff that test positive for the virus, and absenteeism tied to respiratory illnesses. Moreover, to balance risk of infections with overall child well-being, decision-makers should consider taking a harm-reduction approach that considers not only the number of COVID-19 cases but also child metal heath, food security, and academic progress.

As leading pediatricians and educators have emphasized recently, we must make policies based on evidence, not fear. And we should not apply the same metrics to closing bars and gyms as we do to closing schools. Which is more important? Schools and child care should be one of the first parts of society to reopen, not the last.

We owe it to our children to make data-informed decisions that affect their education, development, and well-being. Continuing to reopen society for adults without considering children puts their futures at stake.