Week number two of the COVID-19 pandemic was quite possibly as head-spinning as week one from this school psychologist’s perspective. The reality for professional educators, students, and parents has settled in — we’re adjusting to new routines, or not, in some cases.

Our homes are our new classrooms and offices. Colleagues are connecting on various virtual platforms, but it doesn’t replace the personal connections we all need daily. I’m holding out hope that in the coming weeks and possibly months, we can sustain the social emotional skills we currently have and build new ones along the way.

The very first International SEL (social emotional learning) Day was March 27, and the timing of #SELday couldn’t have been more perfect. It’s a reminder that our emotional health and our mental health are priorities regardless of what life brings.

What exactly is social emotional learning, and when did it become so embedded and prioritized in the instructional conversations in our schools? To truly have this conversation, I’ll need time to explain. In fact, I’ll need to pull in several perspectives to build the understanding of how children are nurtured by their environments at home, at school, and in life.

In a world filled with risk factors for our children, it’s up to whole communities to build and support the resiliency factors our children will need to live in a complicated 21st century world. The goal is to grow thoughtful humanitarians who will understand the importance of leaving the world intact and peaceful for the generations behind us. During COVID-19, the patience and diligence needed to adapt to this shift in daily living is key.

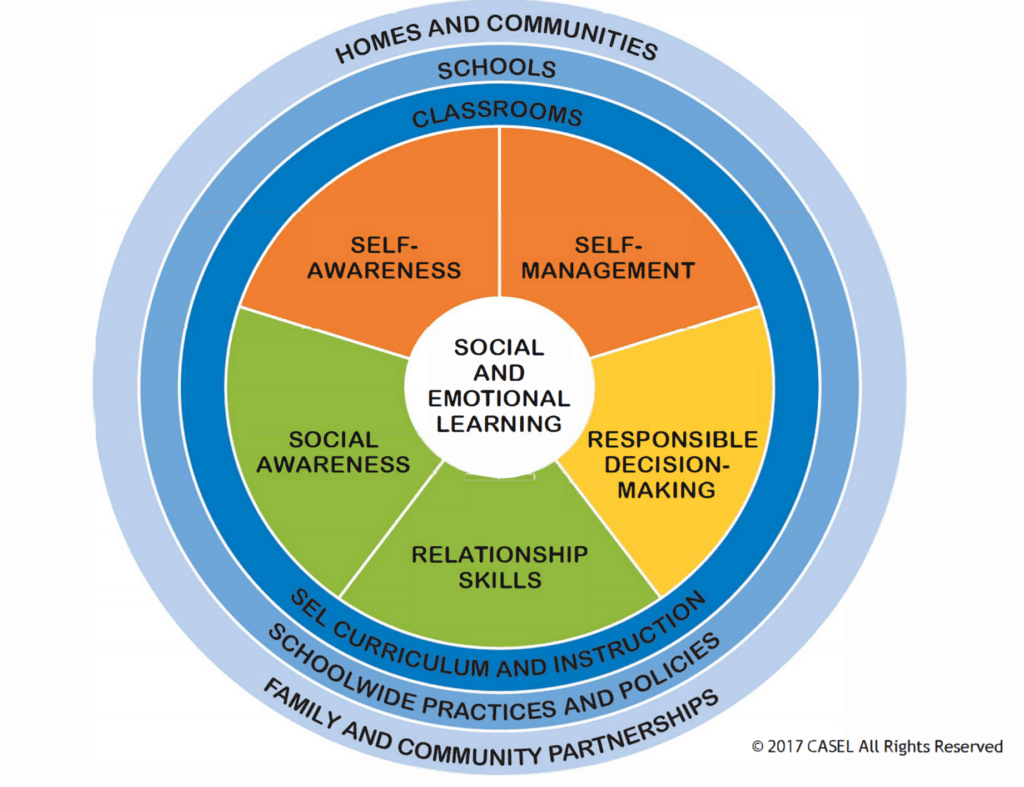

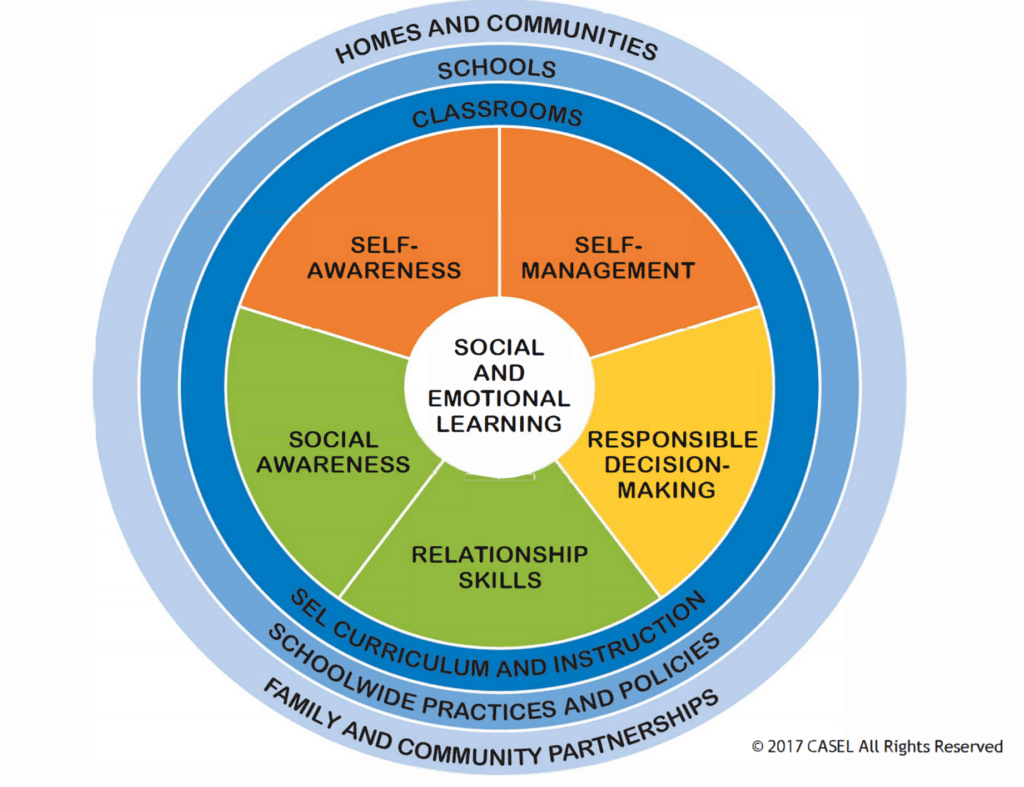

According to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), social and emotional learning skills include self-awareness, relationship skills, social awareness, responsible decision-making, and self-management.

My personal favorite, embedded in social awareness, is empathy — an essential skill for school psychologists and our partners in schools. Social emotional learning is often viewed as the “soft skills” in school and life, but as a school psychologist, I know these to be essential. From the moment I meet children, I’m working to support these skills.

SEL has historically been viewed more as a side dish to the main course of academic instruction, but school psychologists and the teams we work with in schools (school counselors, school social workers, and school nurses) have always known the importance of SEL through the lens of the whole child.

When the collective effort of school psychologists and school teams truly works, there is only a small, dedicated group of people and the family of a struggling child who truly understand this. If our work is successful at the most vulnerable time in a child or family’s life, it’s often unprovable in the moment.

The hidden success of our daily work with the fragile humans in schools is measurable mostly over time as we watch them finish elementary school, make friends, reunite with their loved ones, overcome suicidal ideation, and return to school, graduate with their class, and experience other life events most people take for granted.

Our rural communities without a full-time school psychologist to address the SEL needs of students during this time may be wondering when funding will catch up with their communities’ needs. At a time when North Carolina’s business community and elected officials are increasingly recognizing the value of SEL that professional educators, universities, and those in the mental health profession have long-known, there is tremendous hope that funding will then be attached to strengthening the school psychology and other specialized instructional support workforces suited to address SEL in schools.

It’s not too late to celebrate #SELday this week, and remember that with a statewide shortage of school psychologists, all North Carolina children need access to professional educators who support these skills.