An intentional, coordinated effort by Lenoir County Public Schools to strengthen the connection between teachers, students and parents has cut the number of out-of-school student suspensions by more than half over the past five school years.

The district recorded 2,258 short-term suspensions – those of 10 days or less – in 2015-16 but just 1,065 last school year, a reduction of 53%, according to preliminary data the district has provided the N.C. Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) and reported to the Lenoir County Board of Education.

The five-year trend shows declines each year; even the truncated 2019-20 school year would have totaled about 100 less than the previous year when adjusted for the difference in weeks of instruction. The downward trend is also reflected across all race and gender categories the district tracks.

“This is not a one-off,” Assistant Superintendent Nicholas Harvey II said. “This is an intentional effort by all of us in the school district to keep our students in school because we know suspensions lead to a plethora of other things that contribute to bad behavior long term in students’ lives. Each principal realizes that an out-of-school suspension should and must be the last resort for student discipline.”

The numbers reflect incidents, not individual students; but with fewer incidents drawing out-of-school suspensions, fewer students are removed from instruction – a key element in LCPS’s improved academic performance, district and school administrators say.

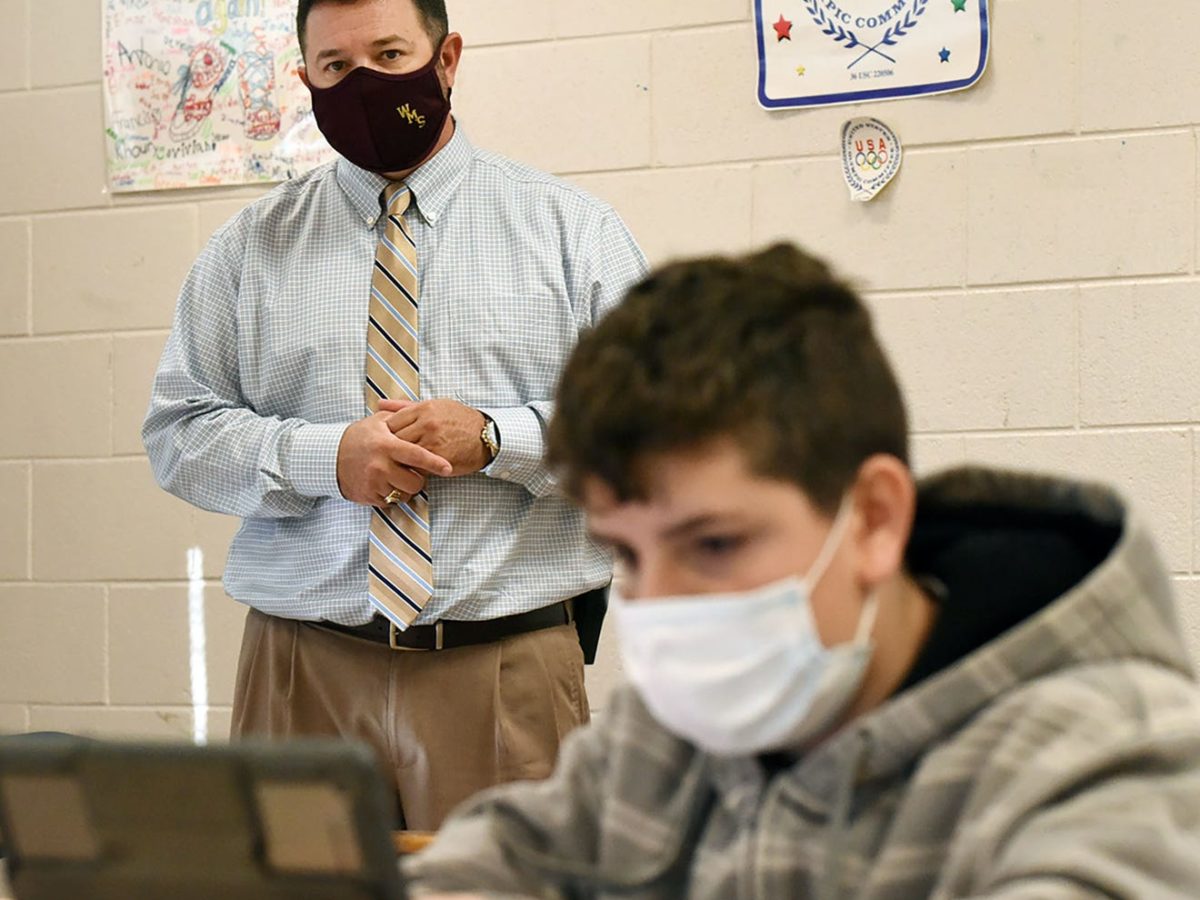

“The teachers are reaching out to the parents. They’re making contact with the parents and they’re building relationships,” Woodington Middle School principal Patrick Phillippe said. “That’s the big thing – they’re building relationships with parents to let them know that if we all work together we can keep their kids in school, in class, and get them what they need.”

Woodington’s suspension numbers have fluctuated during the five years from a high of 189 in 2016-17 to a full-year low of 140 in 2018-19. Last school year, the school recorded 55 incidents before classes were suspended in mid-March. “We were on track to be under a hundred,” Phillippe said.

The middle school has developed a graduated response to most discipline issues that range from a teacher-student conference for a first minor offense to lunch detention for a third. “Every time there’s an infraction, parent contact is made. On the third infraction an actual parent conference is required; on the fourth referral, that’s when they come to an administrator,” Phillippe said.

District-wide, a more flexible approach to discipline hasn’t opened the door to more problems; instead, the reverse has happened. Reportable offenses – issues like assault, possession of alcohol or a controlled substance or possession of a weapon that must be reported to NCDPI – declined in every category during the four full school years between 2015-16 and 2018-19 and total offenses fell by nearly two-thirds, to 29 from 79.

There’s still a line students should know not to cross, according to Phillippe, but teachers and school administrators also have some latitude in dealing with most infractions.

“Certain things – a fight, drugs or a weapon or using profanity toward a teacher – those are automatic. You’re coming to see an administrator,” Phillippe said. “A kid who’s had a perfect record and never been in trouble and just gets tied up with something where he’s just made a bad choice, are we going to throw the book at him?”

While disciplinary systems at the 17 LCPS schools may vary in detail, they all blend programs that reward good behavior with a stepped approach to dealing with student offenses, an approach that begins with trying to identify the root of the bad behavior.

“Discipline is not all about punishment,” Northwest Elementary principal Dr. Heather Walston said. “We have to find out what the problem is behind the behavior and solve it so it won’t continue to repeat. We’ve had a lot of conversations (with students) and made a lot of parent phone calls.”

Northwest’s out-of-school suspensions have dropped steadily over the five-year period, going from 83 in 2015-16 to 39 in 2018-19 to 22 last school year.

“The keys are being intentional and being consistent,” Dr. Walston said. “We knew we had to have kids in school learning curriculum. That was a big driver for the staff.”

At LCPS’s three traditional high schools – Kinston, North Lenoir and South Lenoir – out-of-school suspensions dropped from 696 in 2015-16 to 424 in 2018-19 and fell to 268 during the shortened 2019-20 school year. During the same five-year period, all three schools showed academic growth, raised their graduation rates and lowered their dropout rates.

South Lenoir posted the most positive trends – and also showed the most dramatic decline in out-of-school suspensions. In 2015-16, South Lenoir recorded 156 suspensions; in 2018-19, the total was 34; last year, it was 25.

Declining suspension numbers and rising test scores over the long term, especially when both metrics are moving in the right direction across the district, are the best evidence a principal has for creating buy-in among teachers, according to Phillippe.

“The mindset had to change and the teachers had to trust what we were doing. It’s taken time,” he said. “We do a whole lot more counseling now.”

Editor’s note: This piece was first published by the Kinston Free Press. It has been posted with the author’s permission.

Recommended reading