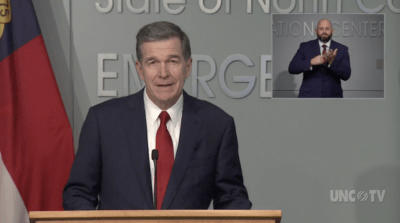

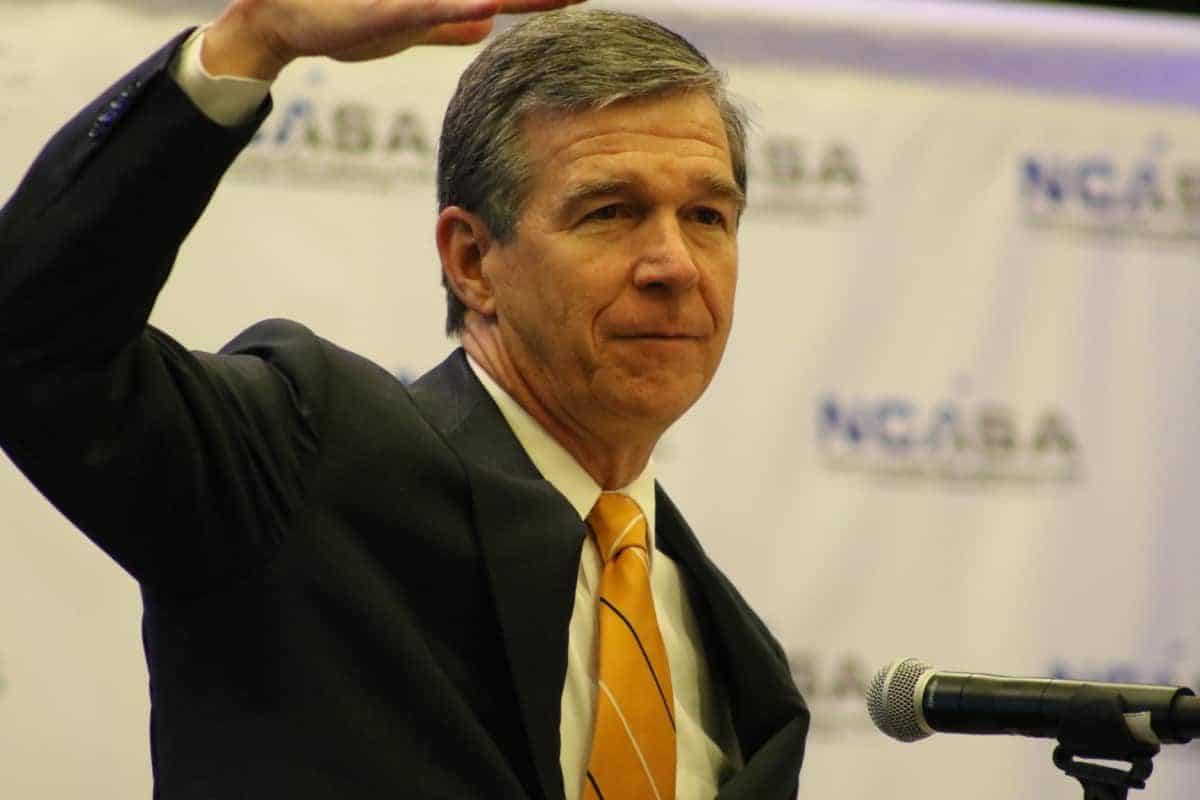

My friend and faculty colleague Thad Beyle, who died two years ago, spent his long career as a political scientist teaching state government and politics while studying the governorship of the American states. I thought of Thad after watching the televised briefing in which Gov. Roy Cooper, one of his former students at UNC-Chapel Hill, delivered his decision on resuming public education across North Carolina.

The disparate ways governors have dealt with the confluence of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement offer students, not to mention adult voters, real-life civics lessons. In a sense, this is a Thad Beyle moment — to apply his research to assessing how governors, as well as certain big-city mayors, used their decision-making in shaping the nation’s course through a stressful and painful period.

For several weeks, cable TV networks featured the chart-laden briefings of New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo as a counterbalance to President Trump’s coronavirus press conferences. Now, governors of Florida, Texas, and Arizona, where COVID-19 has spiked, find themselves in the media glare for having resisted ordering early lockdowns.

Thad taught that governors have two broad categories of power: 1) “formal institutional powers’’ such as to make appointments, to control the budget, and to veto legislation, and 2) “informal powers’’ such as political alliances, access to the news media, and “good looks, charisma, and overall political popularity — which itself can rise or fall with each new political brushfire.’’ In his rankings of governorship, Thad placed the North Carolina governor among the weakest in formal powers. He would certainly see a classic constraint inherent in a governor facing a legislative majority of the opposing political party.

Completely unanticipated, the North Carolina governorship as an institution has gone through an extraordinary period over the past four months. Events have tested Cooper’s use of both formal and informal powers as they would have any occupant of the office in these times.

In late March, the governor issued a sweeping month-long stay-at-home executive order for all 100 counties. That order, which banned gatherings of more than 10 people, has since been replaced by a Phase 2 that allowed more businesses to open, but is now “paused’’ in light of virus trends.

By adhering to his own data-based criteria for responding to the pandemic, Cooper ended up in a politically freighted negotiation with the Trump administration over the Republican National Convention scheduled in Charlotte in late August. Nothing quite compares in the state’s modern era to that back-and-forth between a governor of North Carolina and a president of the United States. Trump and GOP officialdom decided to move convention events largely to Jacksonville, Florida, where doubts have arisen now over a large indoor gathering amid a viral surge.

A welling-up of outrage — resulting in peaceful multiracial protests along with an outbreak of vandalism and looting in downtown Raleigh — over the killing of Black people by white police across the nation led to Cooper taking an executive action unlike any of his predecessors. Shortly after protesters tore two statues from the towering Confederate monument facing Hillsborough Street, Cooper ordered all three “painful memorials’’ to white supremacy removed safely from the Capitol grounds.

As significant as they are, Cooper’s actions on Confederate monuments and the Republican convention don’t have the impact on the day-to-day lives of North Carolinians as his decisions on preK-12 education. The governor has opted for what is known as plan B; it is not actually a prescriptive statewide plan imposed on every county; it is akin to a Google-map destination plot with alternative routes, caution signs, and travel instructions.

Plan B surely imposes decision-making and fiscal burdens on local authorities, especially district superintendents and principals. It also burdens many parents with a choice of whether to send children back to the schoolhouse, or to have them engage further in remote at-home instruction through the fall.

And yet, despite the uncertainties of a pandemic-induced transition back to school, there is an opportunity afoot to bring back at-risk children into smaller classes where teachers can work with them to catch up from learning loss and provide them with a safe place to nourish their minds and bodies. There is also an opportunity for educators to respond to disruption through innovation in teaching.

In North Carolina as in its sister states, the unexpected pandemic and the renewed attention to the history of racism have shed light on gubernatorial leadership, while also requiring the often-uncelebrated work and initiative of mayors, governing boards, superintendents, teachers and principals, public health and social workers, research scientists and others in the array of state and local public institutions. Only the federal government, to be sure, has the fiscal capacity to buffer state and local governments from the imminent economic hit to their budgets. Still, Thad Beyle would appreciate this stressful moment for its lessons for students and citizens — that their own state and local governments matter and they can’t look only to Washington for solutions in their own states and communities.

Recommended reading