Fifty-one years ago, Congress enacted and three-fourths of the states ratified the 26th Amendment, which gave 18-, 19-, and 20-year-olds the right to vote. The ultra-swift adoption of the amendment in 1971 responded to a compelling argument arising from the Vietnam War: If you’re old enough to fight in a far-away conflict, you’re old enough to vote.

The intensity of the 2020 presidential election, spurred by the lightning-bolt character of Donald Trump, produced a surge in voter participation across the nation. The Census Bureau reports that 66.8% of citizens 18 years and older voted. Of 18- to 24-year-olds, 51.4% voted.

The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (better known by its acronym CIRCLE) at Tufts University estimates that youth turnout jumped 11 percentage points over 2016. Of young voters, 61% voted for Democratic President Joe Biden, 37% for Trump, the Republican nominee, says CIRCLE.

“White youth voted at the highest rate in 2020 (61%), but youth of color appear to be narrowing the historical gap,” CIRCLE reports. “Young women (55%) voted at a higher rate than young men (44%).”

In North Carolina, more than 5.5 million voters cast ballots, the highest turnout in total votes and share of registered voters since 1972, according to the State Board of Elections. CIRCLE calculates that 55% of North Carolinians ages 18 to 29 voted.

CIRCLE, established 20 years ago, has become a go-to source for data and analyses on civic education and youth engagement. It has just published a new report on developing the next generation of voters.

Despite recent gains, CIRCLE contends, “young people’s participation in our democracy remains inadequate and inequitable.” Among its findings are that rural youth, Black young adults, and young people without education beyond high school have lower rates of participation than their age peers.

CIRCLE has recommendations for government officials, media organizations and journalists, philanthropy, and community organizations, as well as parents. And, of course, it defines K-12 schools as a “critical setting for learning about elections and voting.”

“Starting to teach and inform youth about elections and voting when they turn 18 is way too late,” says the CIRCLE report. It goes on:

“School-based opportunities are especially important for youth who lack such opportunities in other areas, like through their personal networks or experiences with media. And as institutions that reach the vast majority of teens, K-12 schools have a critical role to play in reducing disparities and inequities in civic learning and engagement.”

As institutions, public schools should not engage in partisanship, take sides in voter mobilization, and support or oppose specific candidates — although teachers and administrators retain the rights to vote and to speak as free citizens. Still, public schools are institutions of democratic infrastructure in which the vast majority of American young people encounter literature, civics, and history. When taught well, social studies prepare young people with practical knowledge, experience in critical thinking, a sense of perspective, and a burgeoning desire to participate in the life of their community, state, and nation.

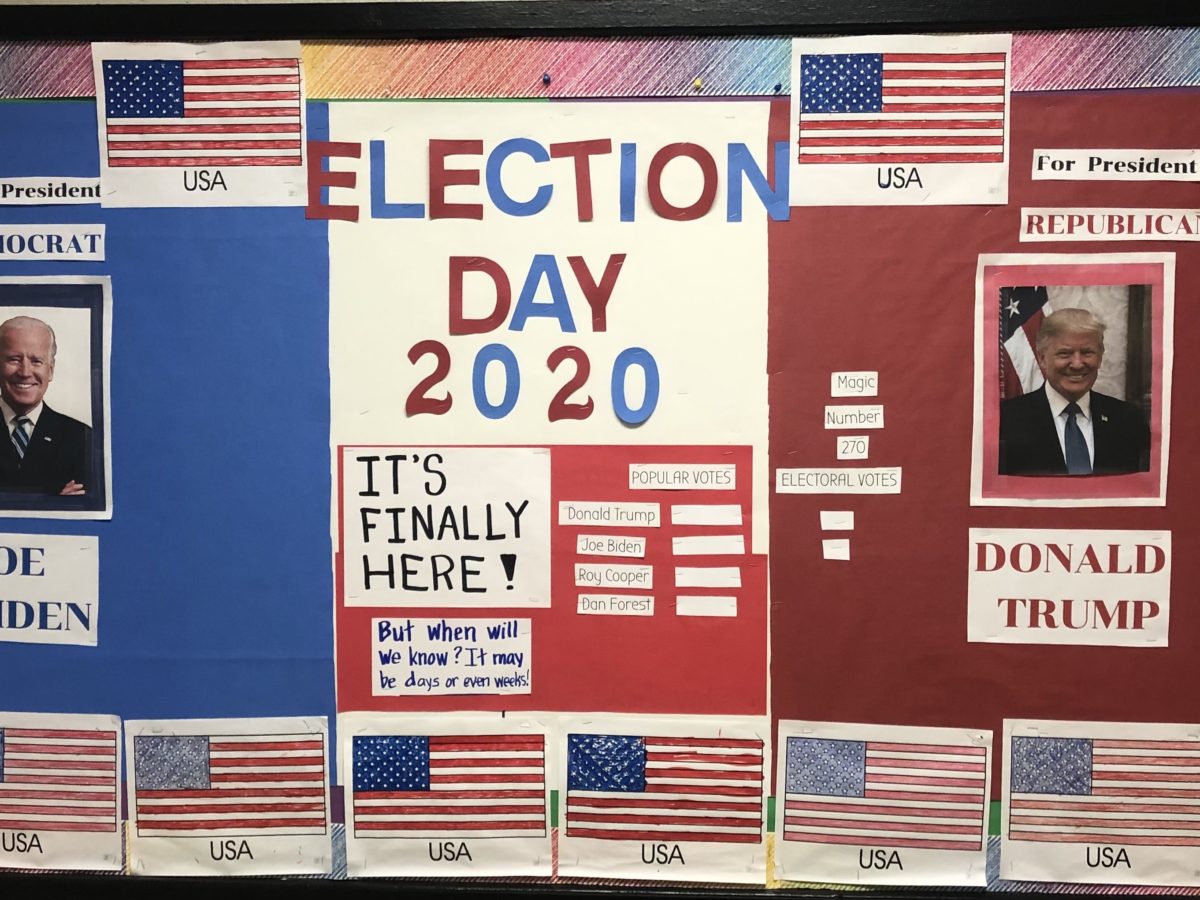

CIRCLE recommends “nonpartisan teaching about voting and elections across curricula,” thus exposing students to their democratic duties “multiple times in multiple settings.” CIRCLE favors lessons on the history of voting rights, opportunities for in-school voter registration, and for youth poll workers, media literacy education, and efforts to instill in students the practice of civil discourse.

In the immediate run-up to an election, there is no magical solution to stimulating youth turnout outside of campaign debate and get-out-the-vote organizing by candidates, parties, affiliated political groups, and civic coalitions. The CIRCLE report isn’t about short-run tactics or political punditry for the 2022 elections, but rather about ideas over the long-run for preserving and sustaining democracy.

As they move into young adulthood, students now in K-12 schools not only will contribute to the characteristics of the workforce but also will have the potential to become a driving force in the nation’s civic and political life. The undertaking inherent in that constitutional amendment ratified a half a century ago depends on public schools strengthened to sustain a republic.