By sheer happenstance, North Carolina pre-K-12 students went “back to school” this week on the same day that the Democratic National Convention opened. A tenacious virus brought about the coincidence of timing — and impelled both schooling and politicking to go virtual.

The annual first day of school and the quadrennial Democratic and Republican conventions serve as recurring markers in the public life of the United States. Each in their own realm, schools and political parties are basic institutions of American democracy. In today’s laden atmosphere, both face pressures in seeking citizens’ trust while coping with unconventional conditions imposed by the novel coronavirus.

The Democratic Party originally planned to nominate its presidential candidate in mid-July in Milwaukee, but the public health emergency pushed Democrats into a mid-August first-of-its-kind virtual national political convention. Thousands of Republicans were to gather for four days next week in Charlotte; now hundreds will spend a day or so there on party business, while the public sees what the GOP produces for television.

Like the political parties, the schools have turned heavily to digital technology for teaching. Across North Carolina, some school systems have reopened completely online, others with a combination of online and in class. Several have spent substantial funds purchasing laptops and tablets for students. Yellow buses now deliver hot spots for young people to connect to the internet for their lessons.

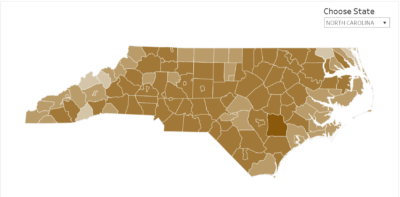

Inevitably in a state with 115 diverse urban, suburban, and rural districts, glitches, missteps, and controversies will arise. But clearly public schools have a lot riding on their performance over the 2020-21 term — not only in delivering quality education to young people but also in expanding the public’s trust.

Shortly before schools reopened, the Gallup polling organization reported that its national survey had found a “record one-year boost in confidence” for public education. According to Gallup, 41% of Americans expressed a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in public schools, an increase of 12 points over last year and its highest rating since 2004.

“Two institutions that have taken on tremendous risks and challenges during the pandemic to fulfill their respective duties for the U.S. public — the medical system and public schools — have earned significantly greater trust from Americans in the process,” Gallup reported. “Several other institutions that have been affected by the pandemic — small business, organized religion, and banks — have also seen a rise in confidence.”

Even if the Gallup finding may offer a morale boost to superintendents, principals, and teachers, it’s prudent to avoid over-interpreting a single survey. As the extensive surveys of EducationNext and Phi Delta Kappan magazine regularly show, the public has complex, mixed opinions on education policies and performance. What’s more, both politics and education policy play out these days in an atmosphere conditioned by decades of declining civic engagement and trust in American institutions.

The legendary political reporter David Broder published in 1972 “The Party’s Over,” a book documenting the effects of voter-fueled primaries, candidate-centered campaigns, and mass media. Fifty years later, reflecting a national pattern, North Carolina has no assured-majority party as young adults increasingly have preferred to register as unaffiliated rather than identify as Democratic or Republican. The current registration pattern shows 36% Democrats, 33% unaffiliateds, 30% Republicans, 0.7% voters in minor parties.

In 2000, scholar Robert Putnam came out with “Bowling Alone,” his exploration of the decline in political participation, membership in civic associations, and informal networks since 1960. In 2008, Texas journalist Bill Bishop published “The Big Sort,” showing how Americans increasingly have chosen to live in neighborhoods and subdivisions where residents live, think, and vote alike.

Perhaps the furor over the U.S. Postal Service will impel many Americans to regain an appreciation for basic, long-enduring institutions that bind people and connect the marketplace in a continent-wide nation. Meanwhile, this is a fraught moment for public schools, colleges, and universities, all of which have yet fiscally to recover fully from the Great Recession.

Just ahead, public education systems face the prospect of another fiscal hit from another recession — all of these foundational public institutions, thus, challenged to demonstrate their value so as to rally political support and public will.