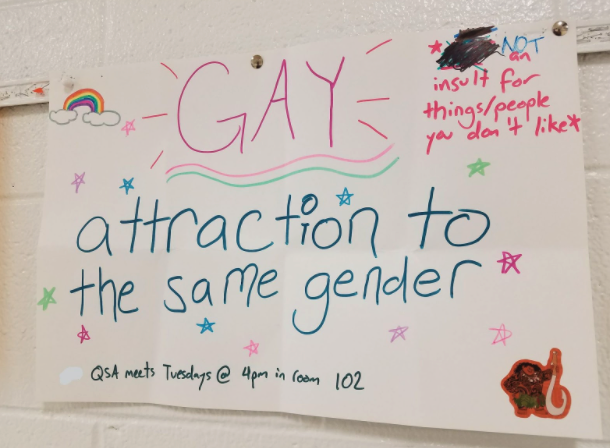

In fall of 2016, my high school’s Queer-Straight Alliance was already on our second set of informational posters. We decided that, as our first project of the school year, we wanted to put posters up around the school that defined different terms used by the LGBTQ+ community. Our whole club worked hard to make them, and then they just … disappeared.

We didn’t think a lot of it the first time, but when we made a second set, those vanished, too.

As a transgender kid growing up in the North Carolina public school system, my experiences were mixed — I had a good group of friends who supported me, and a solid collection of teachers at my Durham high school who made sure I knew I had a safe place in their classroom.

I also had plenty of staff experiences that came from a lack of understanding, respect, or both. Contrary to what anti-bullying propaganda might say, my peers were nowhere near my biggest challenge. As a queer student, I needed protections in policy and support from staff, and in a lot of cases, I had neither.

In many North Carolina schools, there’s a perception that schools are educational facilities first and foremost, and having a queer identity needn’t change the way that teaching happens. But it doesn’t work that way.

One in three LGBTQ+ students report missing at least one day of school per month because of a hostile climate, one in four have been physically harassed and/or assaulted because of their queer identity, and a whopping 85% of trans youth report feeling unsafe at school.

Even with the safety and social implications of these statistics set aside, it’s simply not possible to effectively learn in a climate where a student does not feel safe. Speaking from experience, focusing on a vocabulary test or learning the quadratic formula are not priorities when you’re worried about just making it to the end of the day.

The ramifications of this don’t stop after high school. As a neurodivergent, transgender teenager with deep-rooted perspectives on how school environments just weren’t safe for me, it took me years to be willing to start college.

Even now, my perceptions of educational environments are warped. I often find myself being very careful about how, when, and even if I share my true self within a classroom. I wish I could say I was alone in this, but it’s a common experience for LGBTQ+ youth to find themselves choosing between their comfort and safety and their education.

As educators, the job is never truly accomplished without offering equitable opportunities to all students — not just the ones who are cisgender and heterosexual. Even for those educators who have their heart in the right place, it can be hard to know how to start. As a former North Carolina public school student, I would recommend modeling inclusive education by starting with the following:

- Educators immediately create a safer environment for LGBTQ+ students by offering an opportunity on day one for students to share the names and pronouns that honor them. No matter what they say, these identifiers must be respected.

- Normalize LGBTQ+ identities in your classroom. Whether this is queer reading material, gay couples in math problems, or discussing LGBTQ+ movements (like the HIV/AIDS epidemic or the Stonewall riots) that are often left out of mainstream history, adding these as standard practice lets queer students know they’re accepted in your space.

- Watch your language. Gendered terms and divisions aren’t just unnecessary, they’re exclusionary. Instead of lining students up by gender, line them up by style of shoe. Instead of calling your students “boys and girls,” call them learners, world changers, or just people. Instead of asking about Mom and Dad, ask about who takes care of them at home. Empower them, don’t define them.

There are so many ways that North Carolina’s public education system can be altered to support students, but as much as policy change is needed, every loving and accepting classroom makes an impact.

If we really want to teach queer youth in the same way we teach every other kid, we have to start by making them feel safe and letting them know that they matter, too. LGBTQ+ students deserve a real opportunity to be successful, and it is the job of policymakers and educators alike to make sure they have that opportunity.