One day in the mid-1960s, as a student at Loyola University New Orleans, I encountered an unexpected installation in the upper reaches of the campus library: a wire-fence enclosure, with a locked gate, containing stacks of books. When I asked about the cage, the library staff said it contained volumes on the Roman Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books.

A Jesuit university founded in 1912, Loyola struck a balance, accumulating books worthy of academic study while limiting access to approved scholars. Then in 1966, bowing to modern reality, Pope Paul VI abolished the notorious index. The old library with the book cage is long gone, and Loyola has a handsome, vibrant library worthy of an intellectual center in New Orleans and the South.

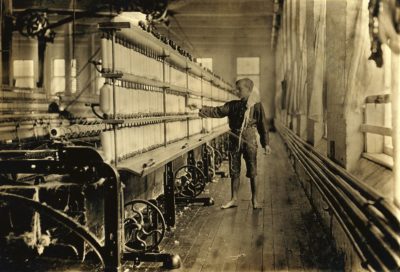

Now, in North Carolina and across the nation, state and local authorities have either exerted or bowed to political demands to erect virtual fences around civics and history classrooms in public schools. These legislated fences seek to restrain teachers from forthright instruction and discussion of race in America, its history and legacy, at a time when students especially need fuller knowledge to comprehend the current condition of their society and democracy.

The pressure on educators reflects the distemper of our times, defined by the Jan. 6 raid on the U.S. Capitol, by unsubstantiated doubts on the outcome of the 2020 presidential election, by persistent opposition to mask-wearing and vaccination to quash a deadly virus, and by disinformation spread online. Schools have become contested spaces in the partisan-tinged run-up to the 2022 elections and in the larger struggle over democracy itself.

After the National School Boards Association sent a letter to President Joe Biden to express its alarm over threats, harassment, and violence, the U.S. Justice Department agreed to deploy the FBI to assist K-12 authorities. Officers of the North Carolina School Boards Association sent letters to the governor and legislators seeking help to alleviate tensions. National and state Republican lawmakers pushed back, warning against quashing the free speech of parents and constituents of elected boards.

Measures designed to counteract social studies standards for teaching about societal conflicts, embedded racism, and sexism have come wrapped in language of impartiality and even-handedness. The General Assembly passed – but Gov. Roy Cooper vetoed – legislation that would have prohibited teachers from instructions in which “any individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress.” The Johnston County school board adopted a lengthy, winding code of ethics that stated, “All people who contributed to American Society will be recognized and presented as reformists, innovators and heroes to our culture.”

It’s easy enough to express outrage at such efforts to sanitize the teaching of history – or even to parody them. At the moment, my emotion is sadness for teachers left vulnerable and students left short of the sound education in history and civics they deserve. The schoolhouse doors can’t block the outside world from making its presence felt in classrooms.

A survey of 1,348 teenagers taken this summer by The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Fund found a mix of awareness and anxiety, along with optimism for career success. Reporting on the views of 14- to 18-year-old Americans – white, Black, and Latino — the newspaper wrote, “These young Americans, who are coming of age amid a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, political and social unrest, growing economic inequality and rising crime, are keenly aware of the country’s problems. Majorities view political divisions, racial discrimination, the cost of health care and gun violence as ‘major threats’ to their generation… Nearly half also rank climate change as a major threat.”

What’s to prevent any middle or high school student in North Carolina from raising his or her hand in class to ask a question that calls for a discussion that might make someone else in class feel uncomfortable? Or how are teachers to cover the great political clashes, scandals, and turning points of American history while defining all figures as heroic?

Today’s students live in an environment shaped by 24/7 cable news and commentary and by incessant interchange on the internet. They need teachers empowered, not inhibited, to give them context through the lessons of history and to help them distinguish the reliable from the fake.

Eventually after four centuries, the Vatican learned that in a modern, open society, it couldn’t keep books forbidden in a vain attempt to quash unwelcome ideas and analysis. It’s a lesson for North Carolinians tempted to erect fences around their classrooms that would deprive students of an in-depth, nuanced understanding of our democracy and its history.