State education officials gave parents indirect, yet sound, advice about the new A-to-F grades applied to public preK-12 schools across North Carolina: Don’t pay the grades any attention.

In both concept and execution, the letter grades were simplistic and flawed from the start. And the flaws stand out even more clearly as the state’s schools continue to cope with the strains imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As required by law, officials dutifully released and posted online the letter grades and the low-performing designations. Not surprisingly in light of the pandemic, the number of D and F grades rose, now marking two-fifths of the state’s 2,595 traditional and charter schools. One-third fall into the low-performing category.

“I will ask that no one else refer to these schools as low-performing schools — they are schools designated as low-performing,” Deputy State Superintendent Michael Maher said, as quoted in a thorough report by EdNC’s Rupen Fofaria from the state Board of Education meeting last week. The low-performing designation, said Maher, “is not an accurate reflection of the efforts and progress of teachers and school leaders throughout this state.”

The A-to-F grades originated in the 2013 package of education initiatives of the Republican majority in the General Assembly. That package also contained a third-grade reading mandate, an expansion of charter schools, and tuition subsidies for lower-income students in private schools.

Under the law, each school gets marked with a single-letter — A, B, C, D, F — calculated according to a two-part formula: 80% based on students’ scores on standardized tests and 20% based on students’ performance over a school year. The formula, thus, puts excessive weight on moment-in-time test scores and not so much on educational progress made through the interaction of students and teachers over the course of a year, commonly referred to as “growth.” Schools with D or F grades are designated low-performing unless they exceed their growth target.

The misleading simplicity of the letter-grades and low-performing designations is underscored in the School Reports Cards section of the Department of Public Education website. There, parents can find 25 data indicators for each school in the state — ranging from end-of-grade tests, to advanced course enrollment, school safety, attendance and absenteeism, educator qualifications, and per-pupil expenditures.

Even those 25 metrics don’t tell all, says DPI: “Parents and others should note that the information in the School Report Card, while important, cannot tell you the entire story about a school. Other important factors — the extra hours put in by teachers preparing for class and grading assignments, the school spirit felt by families, the involvement in sports, arts, or other extracurriculars — are crucial aspects of a school community, but are not reflected on the Report Card.”

Of course, policymakers, educators, and parents need data to measure progress, identify achievement gaps and inequities, and drive educational reforms. In a democracy, citizens deserve an accounting of the performance and needs of their public educational institutions.

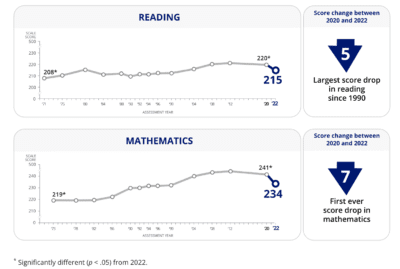

Even as North Carolina officials were considering the state’s accountability data, federal officials reported the sobering decline of 9-year-olds’ performance on math and reading in the National Assessment of Educational Progress. “It’s clear that COVID-19 shocked American education and stunned the academic growth of this age group,” said Peggy Carr, director of the National Center for Education Statistics.

Both state and federal data point to the pandemic having widened the gap between higher-performing and lower-performing students. In North Carolina, year after year, most of the schools graded D or F had enrollment largely of students from low-income households, while schools serving more affluent students had A and B grades.

Addressing the needs of distressed schools and their students is at the core of the long-running, long-range case now before the state Supreme Court, which heard arguments on the day before the education board meeting. The immediate question is whether the justices should reaffirm a Superior Court order, opposed by Republican legislative leaders, to spend $785 million to implement two years of the proposed comprehensive remedial plan.

Beyond that narrow, albeit crucial, question, North Carolina faces the broader challenges of supporting and sustaining academic recovery. Simplistic letter grades won’t lead to educational enrichment. Given the infusion of federal funding and its own capacity for raising revenue, North Carolina can act as the mega-state it has become to put public education on a trajectory that enhances the chances of all of its young people to thrive in economic and civic life.