Over the last decade, I’ve visited dozens of schools across the state listening to the perspectives of teachers and principals about various education policy reforms and school improvement efforts.

A recent partnership grant with the North Carolina State Board of Education provided an opportunity to hear the voices of educators currently employed in some of the lowest-performing schools in North Carolina. Not surprisingly, we heard about the uphill battles these schools face due to policy-relevant barriers such as insufficient teacher pay and poor working conditions. However there was also a strong consensus among educators around another core building block, considered to be essential for successful school improvement: the need to cultivate mutual trust, and develop strong interpersonal connections, with whomever is delivering supports at any level.

With this in mind, one of the first things that struck me in our evaluation of Schools That Lead (STL) was the extent personal interaction and relationship building was a continuous and prominent focus throughout all the tools and skills being adopted by educators. Schools That Lead (STL), a nonprofit education organization that forms networks of educational practitioners, aims to solve intricate problems and accelerate improvement in schools. The cornerstone of STL is improvement science, a methodology that tests change ideas and advocates continuous learning.

Findings from year two of the STL evaluation surfaced overwhelming praise for Dana Diesel, CEO of Schools That Lead, and Sofi Frankowski, STL’s chief learning officer – essentially unanimous across 174 open-ended survey responses with STL participants, and key-informant interviews with school leaders and teachers. While personal connection is difficult to quantify, the qualitative feedback specific to Dana and Sofi was remarkable – lauded by multiple educators as one of the most impactful partnerships in their education career.

The payoff of intentional relationship-building is evidenced first in the strong connection developed between educators and STL coaches, which ultimately flows down to the benefit of students. Educators feel heard and empowered by the relationships they establish with STL, which translates to students who feel heard and empowered by the relationships developed with the educators in their lives.

There are multiple elements that set STL apart from traditional school improvement interventions. The most prominent differentiating characteristic is that it champions starting small, rather than rolling out changes that impact entire schools or districts and result in waiting for extended time periods to determine effectiveness.

The STL model acknowledges and addresses one of the greatest challenges in school improvement – while there may be agreement around the broad elements needed to support effective teaching and learning, the reality is that these problems are incredibly nuanced by nature. Too often this means that educators either suffer from analysis paralysis, or from the consequences of taking an ineffective approach to solving critical problems.

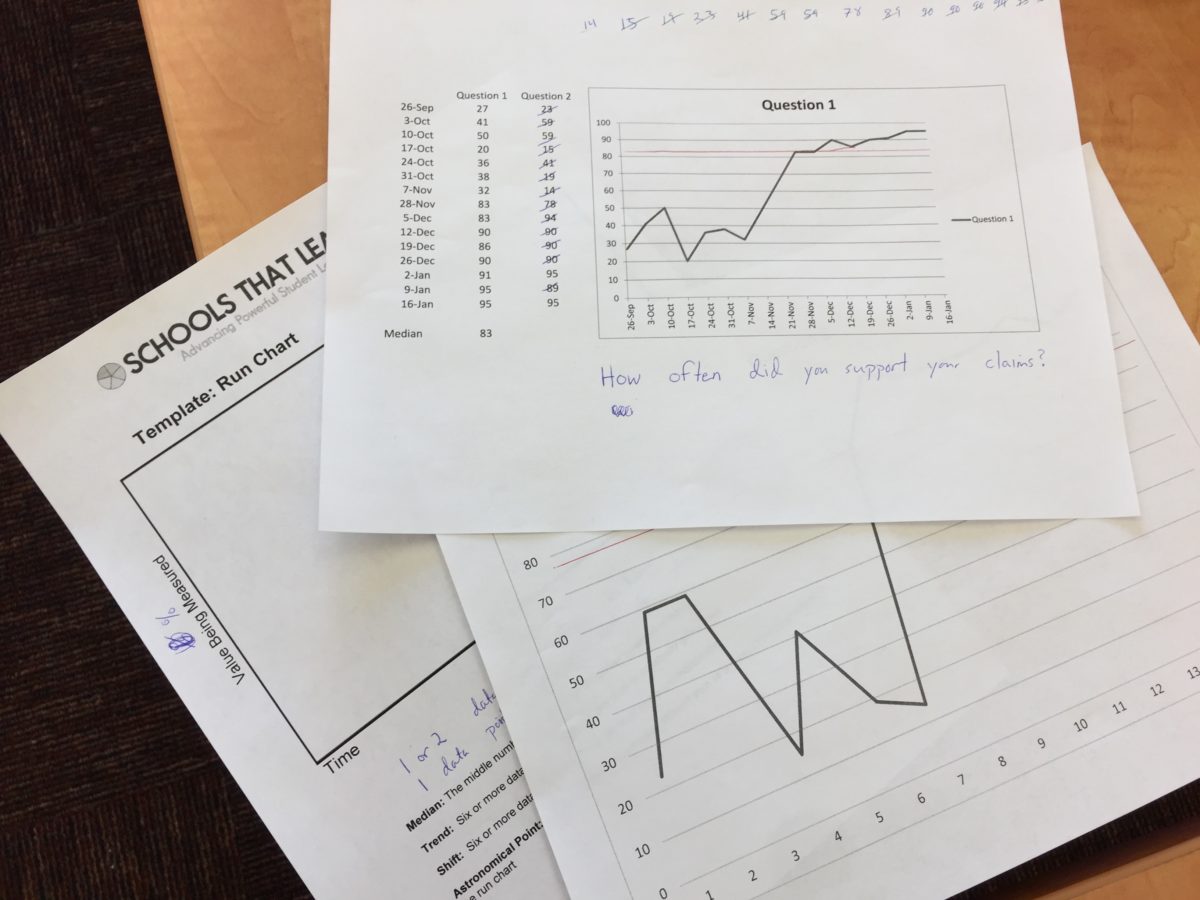

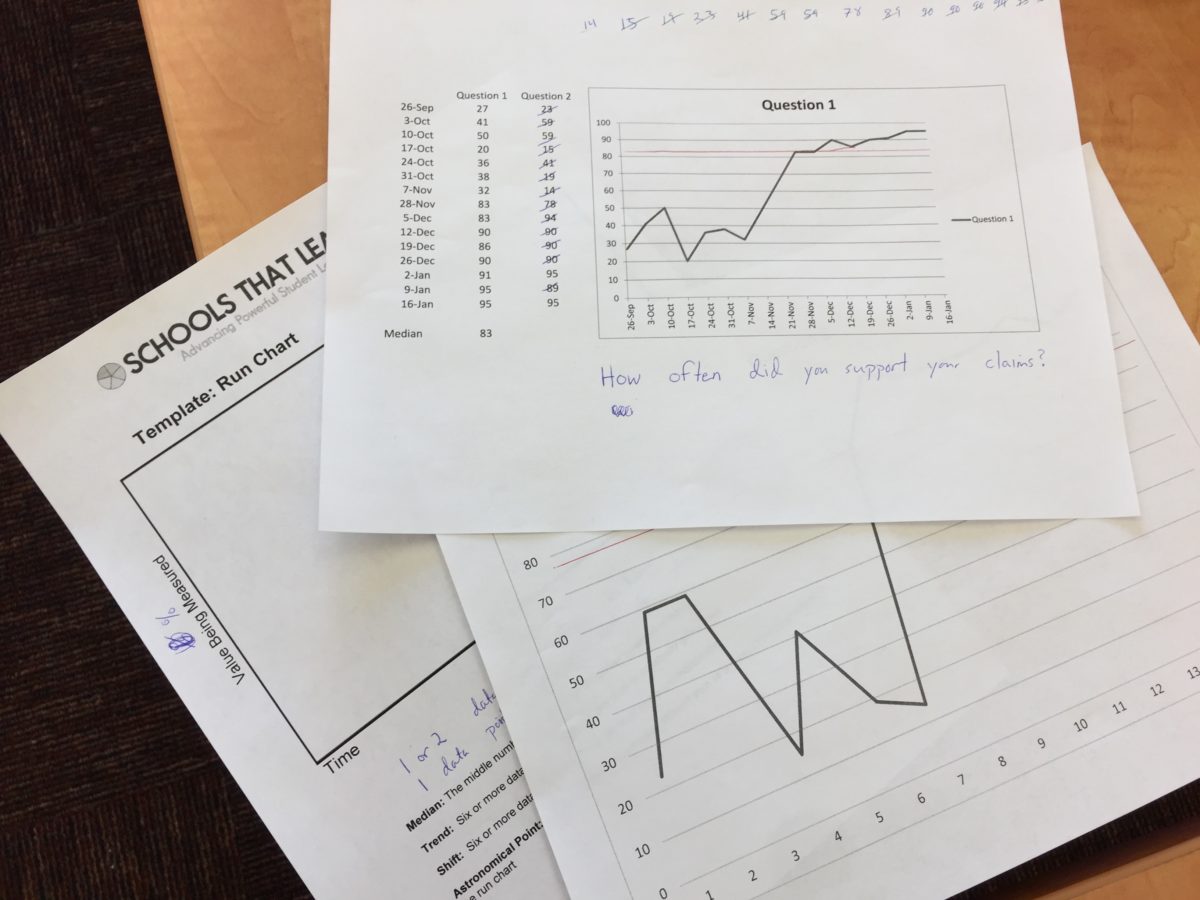

In contrast, STL equips educators with tools to identify pressing needs and to develop strategies for rapidly testing potential solutions at a manageable scale. This affords teachers and principals the opportunity to begin paving a data-driven path to school improvement that is responsive to the unique contexts of each school and the students they serve.

Empowering teachers from start to finish

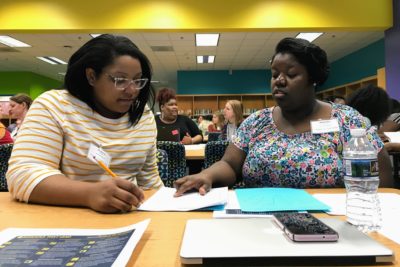

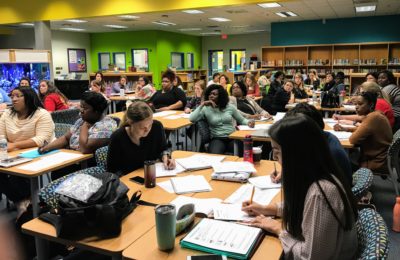

STL is focused on helping teachers understand the why behind the practices and processes they are being encouraged to implement. STL hosts small, intimate sessions – an environment conducive for interaction and practical application. This is a huge paradigm shift for many educators who are used to changes that are strictly top-down, without explanation and without opportunities for input.

In STL sessions, there’s a blend of instruction, along with time set aside for the sharing of knowledge and resources. The STL coaches explain the science, present the research, and show teachers how to use the process. Teachers then create a watch list for key indicators of student success, and decide on benchmarks tailored to the unique context of their own school.

Another novel aspect of STL’s training is to ensure there are opportunities for educators to put new strategies into practice before leaving the training session. This allows educators to struggle, ask questions, and learn from others in a safe environment before implementing changes in their own schools.

The STL approach diminishes the intimidation teams face in solving complex problems – not only does the coaching encourage educators to start small and then begin to build things out from there, but it incorporates a hands-on approach where coaches roll up their sleeves and join school teams to physically get them started. Educators reported that unlike most other school improvement “trainings”, they walk away empowered, understanding why the process works, and with confidence from already getting the work started. In my experience, once educators get started, that momentum sustains their commitment to do whatever is needed to finish.

Leaving a mark

Starting small in order to get something right also means more time is needed to see change at scale. Adding the unknown ramifications of mandatory remote learning last spring, this was clearly not the time for empirical school and district-level outcome metrics.

In lieu of analyzing administrative data, the mixed-methods approach to this evaluation allowed for triangulation of evidence across multiple data sources and multiple stakeholders. The findings were compelling, as exemplified by an anonymous web-based survey completed by over 150 STL participants. The findings were striking, with 100% of STL participants at the high school level, and 90% of participants at elementary and middle school levels, reporting that they were confident their work with STL would result in substantial policy-relevant outcomes. There is a substantial evidence base that these types of changes, ranging from chronic attendance issues to on-time graduation, would markedly improve the lives and educational trajectories of children across the state.

While successful school improvement is undeniably an arduous journey, STL is facilitating a novel model for change that is guided by paths built by educators from the ground up. The formative evaluation findings, along with the momentum established and maintained by many of the participating schools, paints an encouraging picture around the potential to begin reshaping the topography of North Carolina’s education policy landscape.