Over the past three months, our team from the Empowering Teacher Learning (ETL) project at Appalachian State University has been traversing western North Carolina and engaging with over 300 middle school educators in their classrooms. With research funding from the U.S. Department of Education, the ETL project will measure the impacts of a teacher-directed professional learning program in rural, western North Carolina middle schools with the goal of supporting efforts to shift the way in which teachers engage with professional learning and maintain licensure.

It is no secret that there is a growing need in North Carolina to find ways to retain and support educators, especially those who have facilitated learning throughout a global pandemic. A study from Johns Hopkins University found that educators were 40% more likely to report anxiety symptoms during the height of the pandemic than healthcare workers. Additionally, educators who were forced to teach remotely “were significantly more likely to report feelings of isolation than were those teaching in person.” What is striking about this report is that these are the findings about our educators’ mental health. Imagine how our students felt sharing the same experience.

In addition to the complications caused by the pandemic, we notice that society is eager to embrace a negative narrative around our schools and to allow that narrative to drive the conversation. In education, we search for an instrument of measurement that allows us to paint our schools with broad strokes, forgetting that while the education system is large and expansive, the daily experiences of teachers and students are granular, composed of many complex and nuanced interactions. Unfortunately, our need to establish markers for success leads to common oversimplification of a necessarily complicated situation, and in this case, at the expense of educators and students.

This begs the question: How should we be comparing the success of schools and students, and how can these generalizations be used in a way that promotes positive growth in measurable student outcomes? Thankfully, a conversation has begun about making changes to the ways schools are evaluated based on the survey conducted by EdNC. Results show that 90% of respondents believe school performance grades should include measures beyond test scores and student growth. We couldn’t agree more.

Our work through the ETL project empowers educators to take ownership of their professional growth in order to improve their practice. It is vital for North Carolina to invest in its educators by supporting flexible, self-directed learning opportunities that treat them like the professionals they are. Our research is especially timely in light of a recently released report by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction that labels one in three NC schools as “low-performing,” including many of the schools in our network.

While this project recognizes the necessity for raising awareness of students’ struggles, much of the blame is systematically laid on educators and administrators. This label perpetuates a narrative that is discouraging and demoralizing to our schools and to our communities, and it must be addressed.

We collect a lot of data for our work, but one particular part of the project stands out as being special: classroom video recordings that educators can use as a means to reflect on their instruction. Unlike traditional video recordings mandated for edTPA or National Boards, these video observations are utilized in one-on-one meetings between the teacher and an ETL coach. This exercise allows educators to view their classroom as an outside observer so they may notice the positive interactions that lead to student success, thereby guiding educators’ professional learning goals.

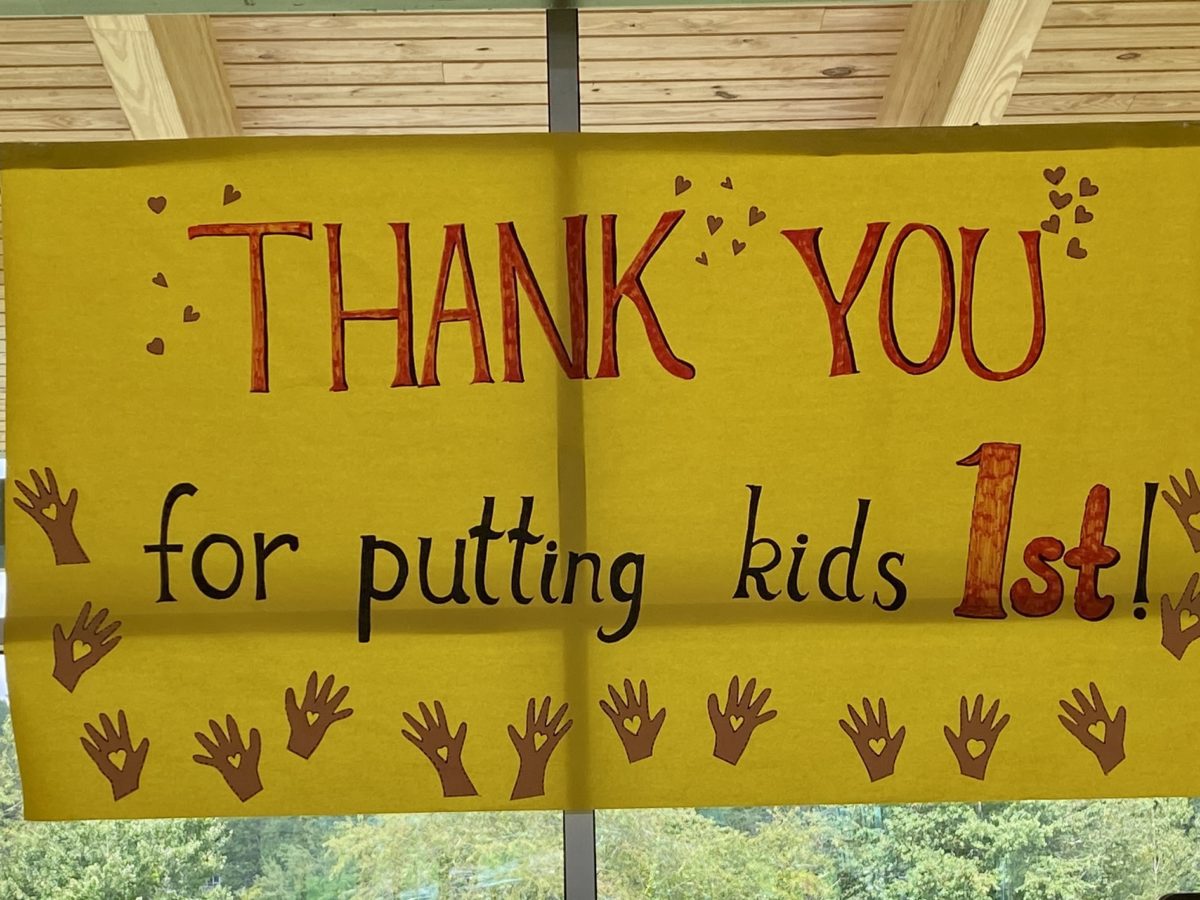

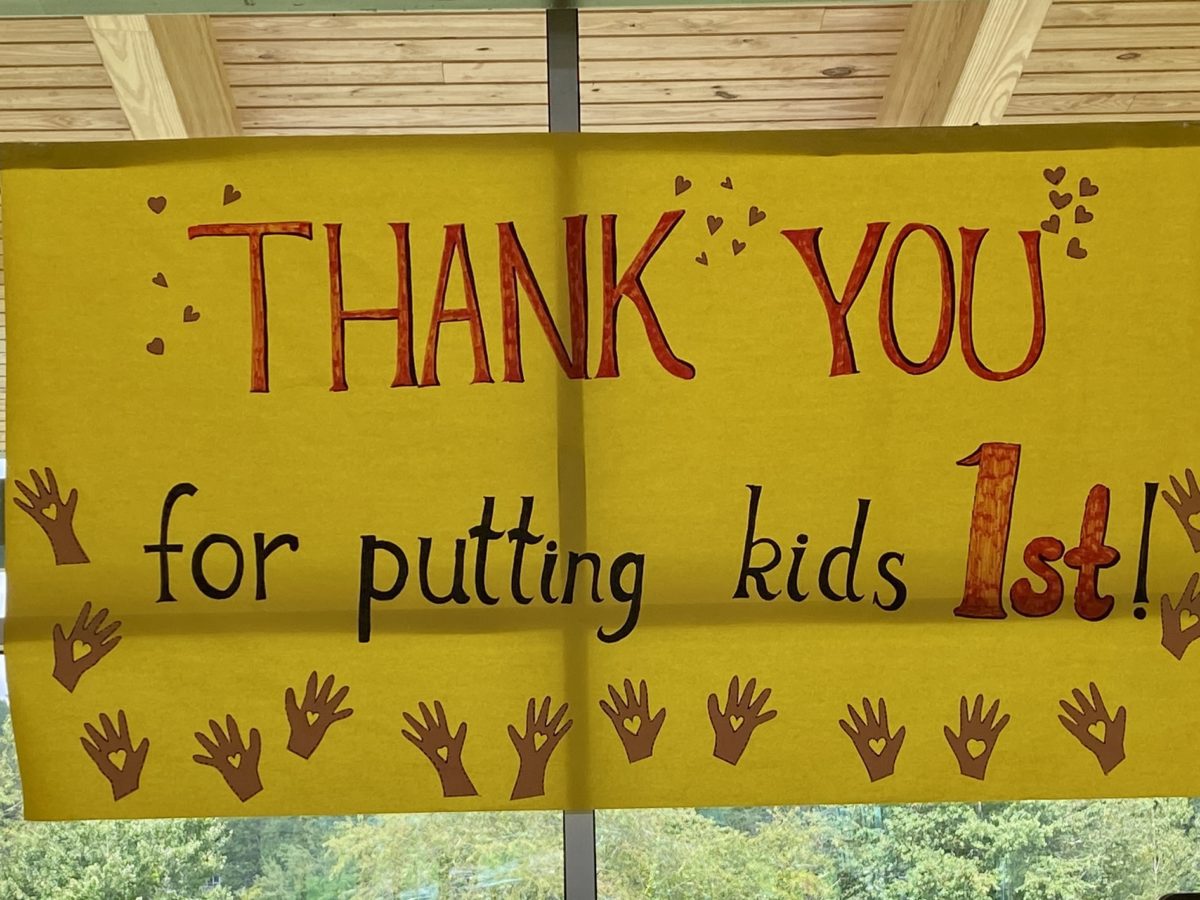

Our observations have allowed us to see first-hand that North Carolina educators and students are anything but “low-performing.” Having visited over 30 schools across 12 districts, our team witnessed much more than a dedication to provide North Carolina students with a “sound basic education.” The care and concern North Carolina’s educators have for their students was evident in every school we visited.

In fact, despite the lasting effects of the global pandemic, the educators and students we have observed are thriving. While our team is not looking at test scores when we visit these schools, we are witnessing the effort, cooperation, and eagerness that students have while participating in the learning process. For example, genuine excitement filled the classroom of a science teacher who conducted an experiment on closed versus open chemical reactions. In a social studies class, curiosity permeated the room as students leveraged virtual reality to explore the tombs in ancient Egypt. We witnessed shouts of joy and high fives in math class, where students competed to solve multi-step equations quickly and accurately. Our team’s time in classrooms made one thing perfectly clear: excellent things are happening in western North Carolina schools, and teachers should be recognized for their efforts and accomplishments.

We are proud to say that the Empowering Teacher Learning project is working to do just that, empower teachers. While our project is just one small step towards giving our teachers the respect and autonomy they deserve, we hope it can bring about small changes in the ways we view professional learning. Overwhelmingly, research suggests that teacher quality has the biggest impact on student achievement. This is why we highly suggest our state continues to look to our educators for answers to these difficult but necessary conversations, because they are always the ones with the answers.