Mother Nature has blessed North Carolina with a gloriously vivid fall. Red maples have punctuated the treescape with exclamation points.

As usual, at high schools across the state, fall sports drew to campuses parents, grandparents, friends, and classmates as spectators. The women’s tennis season just concluded with eight new champions, and the football playoffs move along through November. The lights of Friday nights illuminate that schools help forge community and neighborhood identity.

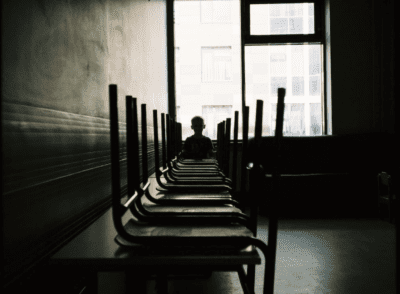

And yet, the fall of 2022 has had a duality that Dickens would understand: “It was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness.” North Carolinians, like their fellow Americans, are agitated and at odds, their anxiety stoked by midterm elections that seem more consequential than usual.

North Carolina’s political climate aligns with the national climate. In survey after survey, the Pew Research Center has documented the partisan divisions across many dimensions that define democracy under stress. In the last week of October, Pew released a report with the headline: “Parents differ sharply over what their K-12 children should learn in school.”

Pew reports that a majority of both Republican and Democratic parents say they are extremely or very satisfied with the quality of the education their children are receiving in public and private schools. And two-thirds of parents agree on the importance of schools developing social and emotional skills, says Pew.

In contrast, on gender identity and the legacy of slavery, Pew reports, “there are differences ranging from 23 to 46 percentage points in what Republican and Democratic parents of K-12 students would prefer that their children learn in school. There are also large partisan differences when it comes to what parents want their K-12 children to learn about sex education and America’s standing in the world.”

Elections turn not only on the quality of candidates, their differences on issues, and their hot-button TV commercials, but also on public attitudes shaped by trends and events. The context of the 2022 elections consists of a viral contagion that disrupted business, schools, and families, an assault on the nation’s capitol in an attempt to interrupt the certification of Electoral College votes, the outbreak of war in Eastern Europe that contributed to fuel inflation, and an outpouring of disinformation and conspiracy theories online.

North Carolina’s political landscape arises from three decades of growth and change – in population, racial and ethnic diversity, and the contours of the state’s economy. As metro areas have burgeoned and distressed rural communities have contracted, state and local governments face daunting decisions on transportation, housing cost and supply, shortages of talent in public and private sectors, and crime and personal safety. In mid-October, five people were killed and two injured by shots fired by a 15-year-old in and near a tranquil Raleigh neighborhood.

The Washington Post has tracked incidents of gun violence in schools since the shooting spree that killed 13 people at Columbine High School in Colorado. The Post reports that more than 320,000 children at 340 schools have been exposed to gun violence during school hours since Columbine in 1999 – with 188 people killed and 389 injured. The newspaper lists 20 incidents in North Carolina, including three in 2021 at West Charlotte High School, Mount Tabor High School in Winston-Salem, and New Hanover High School.

“While school shootings remain rare, there were more in 2021 — 42 — than in any year since at least 1999,” the Post reports. “So far this year, there have been at least 24 acts of gun violence on K-12 campuses during the school day.”

In addition to school security, North Carolina has a long, daunting education agenda for the two years between the 2022 mid-terms and 2024 statewide elections – issues ranging from recovery of learning slippage during the pandemic, to teacher compensation and licensing, to the needs of low-wealth schools, to affordable pre-k availability.

Election results for seats on the Supreme Court, in the General Assembly, on county commissions, and on school boards will determine the distribution of power over education policy. And yet, education did not become an out-front, high-visibility statewide issue this year as candidates chose to clash on such matters as crime, abortion and democracy. Moreover, North Carolina’s mid-term elections do not have contests for governor, lieutenant governor, and superintendent of public instruction, offices with education policy roles.

As I was preparing this column and thinking about post-election prospects for public education, WWOZ, the New Orleans jazz station with a livestream to which I often link, played “What a Wonderful World,’’ Louis Armstrong’s most popular, though not his best, work.

I see skies of blue

And clouds of white

The bright blessed day

The dark sacred night

And I think to myself

What a wonderful world.

Yes, it’s a soothing song that reinforces the uplifting sight of fall foliage in North Carolina, a strong state in a nation where a democratic republic has proved resilient for more than two centuries.

Still the realities of today’s national politics intrude into North Carolina. The centrifugal forces of partisan division continue to exert counter-power to the centripetal forces that pull to the center.

Recommended reading