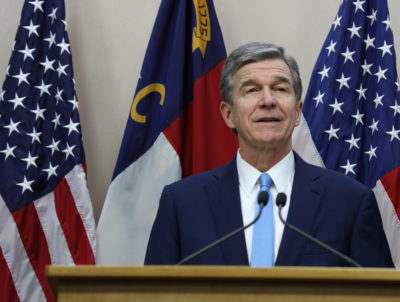

In signaling that he would sign the appropriations bill adopted by the 2021 General Assembly, Gov. Roy Cooper said North Carolina needed a budget, however imperfect, “at this unique time in the history of our state.” Indeed, this moment in time provides a lens through which to assess how public education has fared in the nation’s 9th most populous state.

The governor clearly had in mind the COVID-19 pandemic that closed schools through an academic year. The pandemic made manifest and exacerbated pre-existing inequalities. Re-opened schools now struggle with fatigued teachers and administrators, as well as shortages of bus drivers and cafeteria workers — and they face multiple challenges in helping students recover academically and emotionally.

Pre-pandemic, more than 400,000 students were enrolled in traditional public schools or charter schools categorized as “high-poverty.” More than 840,000 students qualified for free or reduced-priced lunch, a data point used to count students who are poor or near-poor.

Fifty-one of North Carolina’s 100 counties lost population since 2010, even as fast-growing metropolitan regions became stronger engines of economic prowess. The state’s Hispanic population now exceeds one million; meanwhile in K-12 public schools, Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Asian, and mixed-race students now out-number white students.

This moment in state history is also defined by an uncommonly positive fiscal situation for 2021-23. A confluence of factors — federal pandemic relief, state spending held to a three-year-old budget, and state tax collections exceeding expectations — led to unprecedented projections of $6 billion to $8 billion in available revenues. The state has money at hand to launch on all-out assault of high-poverty and low-performing schools.

Superior Court Judge David Lee met the moment. The legislature, not so much.

As the judge assigned to the long-running Leandro education equity case, Lee issued an order on Nov. 10 that $1.7 billion of unallocated state funds be directed to carrying out two years of the “comprehensive remedial plan” he had earlier approved. The Republican lawmakers pushed back. Lawmakers assailed the judge for attempting to trample on the legislature’s power. They approved minimal pay raises and one-time bonuses for educators, shielded local systems from funding cuts due to enrollment decline, but largely spurned the $1.7 billion plan.

The Leandro story will go on, its ultimate resolution still uncertain. But, before turning to the next chapter, it’s worth considering two notable themes in Judge Lee’s 20-page ruling: his expansive reading of the Constitution and his contention that at-risk children are at the core of Leandro.

In response to the legislators’ warnings of a “constitutional crisis,” the judge reads the state Constitution back to the General Assembly, implicitly but clearly. The Constitution contains more than a general provision giving the legislature responsibility for taxation and appropriation. “Multiple provisions,” Lee asserts, require the legislature to fund schools adequately. The Constitution itself, he says, “reflects the direct will of the people.”

“The North Carolina Constitution,” the judge writes, “repeatedly makes school funding a matter of constitutional — not merely statutory law. Our Constitution not only recognizes the fundamental right to the privilege of an education in the Declaration of Rights, but also devotes an entire article to the state’s education system.”

What’s more, Judge Lee’s ruling repeatedly mentions that Leandro has to do especially with the needs of children at risk educationally as a result of disabilities or economic distress in their household. He observes that the state has had an increase in students with “higher needs who require additional supports to meet high standards.”

Since the state Supreme Court ruling in 2004, he says, “a new generation of school children, especially those at-risk and socio-economically disadvantaged, were denied their constitutional right to a sound, basic education. Further and continued damage is happening now, especially to at-risk children from impoverished backgrounds, and that cannot continue.”

A robust initiative through this decade almost certainly would enhance the educational experience of students in both low-poverty and high-poverty schools. For most North Carolina students who move on to and excel at universities and community colleges, public schools are better than ever. Still, North Carolina remains in an extraordinary moment of societal change and educational challenges with an unfinished agenda to lift up young people who would otherwise be left behind.